First published in Great Britain in 2021 by

Michael OMara Books Limited

9 Lion Yard

Tremadoc Road

London SW4 7NQ

Copyright Philip Matyszak 2021

All rights reserved. You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-78929-303-6 in hardback print format

ISBN: 978-1-78929-304-3 in ebook format

www.mombooks.com

Contents

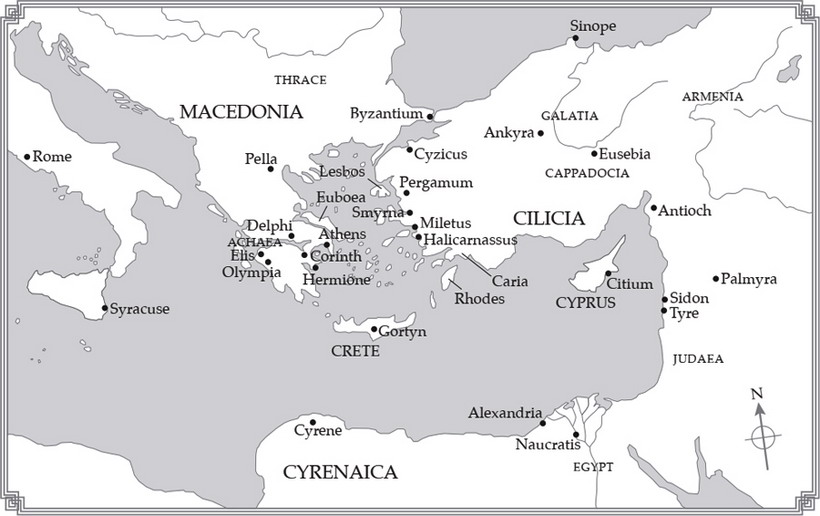

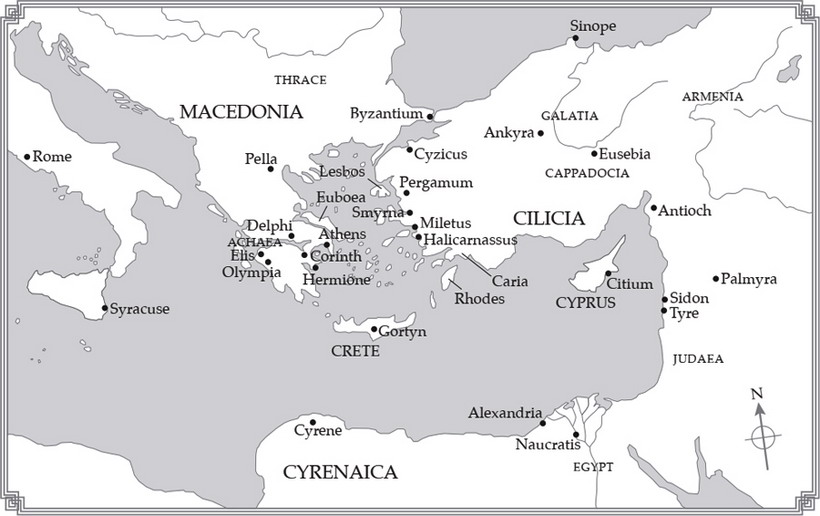

THE HELLENISTIC WORLD

I t is 248 BC, and the start of what is known to the people of Greece as the fourth year of the 132nd Olympiad. At this time, the peninsula of Greece represents only a small fraction of the Hellenistic world (the regions inhabited or colonized by Greek speakers) one already enlarged by colonization but made immeasurably greater still by Alexander the Great, the Macedonian leader who, a century previously, had conquered the East as far as India.

Just over two generations have passed since Alexanders death, but now Greeks battle Indian armies on the banks of the Indus and Spanish irregulars on the shores of the western Mediterranean. Greeks live in the shadows of the pyramids in Egypt and in Alexanders city of Iskandar, which is now Kandahar in modern Afghanistan. It is a vast, strange world, full of danger and opportunity, but it is also a world in which taxes must be paid and routine chores completed every day. The exotic quickly becomes mundane.

Yet no matter how far they may be from their ancestral home, the Greeks abroad remain stubbornly Greek. They still worship their ancestral gods, exercise in their gymnasiums and come from near and (very) far to participate and compete in the already ancient rites of the Olympic Games.

In this book, we follow eight Greeks in very different situations, whose lives are in one way or another touched by the 133rd Olympiad. Though the people themselves are fictional, their lives are not. Each person has been described with the help of modern archaeological advances, which have progressed beyond a search for statues to place in museums to a science that now spends more time excavating dunghills than palaces.

And while palaces might yield golden treasures, there are greater prizes to be found in these dunghills and rubbish dumps, because in them we find traces of the real people of Greece. Not the kings and generals who feature in the histories of Thucydides and Polybius, but the ordinary men and women who paid the kings taxes and died in his armies. Given what archaeologists know of ancient architecture, they can make a fair reconstruction of what a building looked like from studying the foundations alone; we now know enough of the lives of ordinary Greeks to do the same sort of thing in the social sciences to recreate the lives of some ancient Greeks from the evidence of antiquity.

My aim in this book is to reconstruct the everyday lives of these ordinary people and what their world was like in the year 248 BC. At this time, the Greeks of Egypt were building the Great Library and Lighthouse of Alexandria, and elsewhere, science, philosophy and literature were advancing the standard of civilization. Though their occupation of Egypt, Syria and the Levant lasted but a moment in historical terms, to the Greeks of the time, their new, vast world seemed eternal and unchanging. This book reconstructs what it might have been like to live there.

A Note on Chronology

When Thucydides began to write his epic The History of the Peloponnesian War, he found he had a problem with time. Not that he did not have plenty of it, being an exile with nothing else to do, but he lacked the means to describe its passing.

In the modern West, this is straightforward. The years count from an exact date, which was originally (and inaccurately) believed to be when Christ was born. Each year starts on 1 January and, in every Western culture, months have a consistent number of days, with weekends arriving reliably on the sixth day of the week. Thursday, Donnerstag and gioved are all the same day and happen at the same time of the same month.

Ancient Greece could not have been more different. Everyones years started counting from a different date, be it from the founding of the city, a legendary event or the rule of a particularly distinguished individual. Years were named for individual leaders, such as kings or archons, and were different from city to city. Nor did the year start at the same time. Some states liked the idea of starting a year with the autumn equinox, while others started six months later in the spring. Some kicked the year off at the time of a particular religious festival (though no one seems to have chosen the bizarre and arbitrary time of some ten days after the winter solstice, since where would be the sense in that?).

Once the year had begun, whenever it began, the months were not only equally arbitrary but also flexible. If the city fathers decided that the civic calendar was a bit packed in one month, they might extend it by ten days or so, and steal days off other months to compensate. Since no sane landlord would rent a building on those terms, rents tended to be paid according to lunar months, so that in Athens alone there were competing calendars, including the lunar, the religious, the civic and the solar.

The Antikythera Mechanism

To make sense of all this and to date the year in this book, we have adopted the same solution as the Greeks. Imagine you are a merchant from Corinth who wants to buy silk from a dealer in Sardis in Asia Minor. To reconcile the different calendars of the participants in the deal, the merchant uses the worlds first analogue computer.

By inputting the phase of the moon, the time of moonrise and the location of select constellations into the mechanism, the merchant uses it to determine the exact date in Corinth, wherever he might be in the known world. This is then compared with the local calendar and, by advancing the input data to a future Corinthian date, the local date for delivery can be established. So too can the time of expected eclipses and similar phenomena, as well as the dates of great sporting events, such as the Olympic and Pythian Games.

We know the Greeks used such a mechanism because one was retrieved in 1901 from a shipwreck off the island of Antikythera, which lies between Greece and Crete. Since the mechanism was designed to make sense of the chronological anarchy of the Hellenistic era, it seems logical that in this book we should follow the system of the mechanism and resolve all dates to the Corinthian calendar.

By this calendar, our year starts with the autumn equinox, as did each year in the little Peloponnesian state of Elis where the Olympic Games were held. In colder northern climes, autumn sees the dying of the year, but in Greece autumn meant the end of the dry, hot and unproductive summer. It was when the first seasonal rains began to fall, signalling a new beginning.