Table of Contents

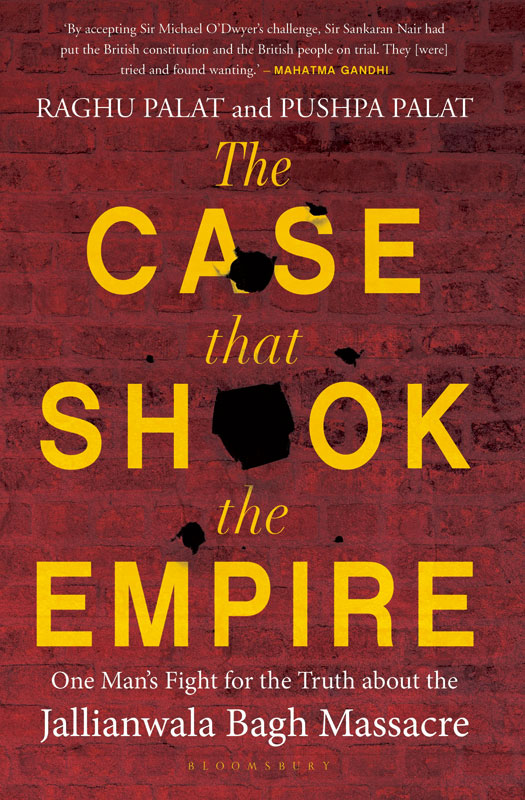

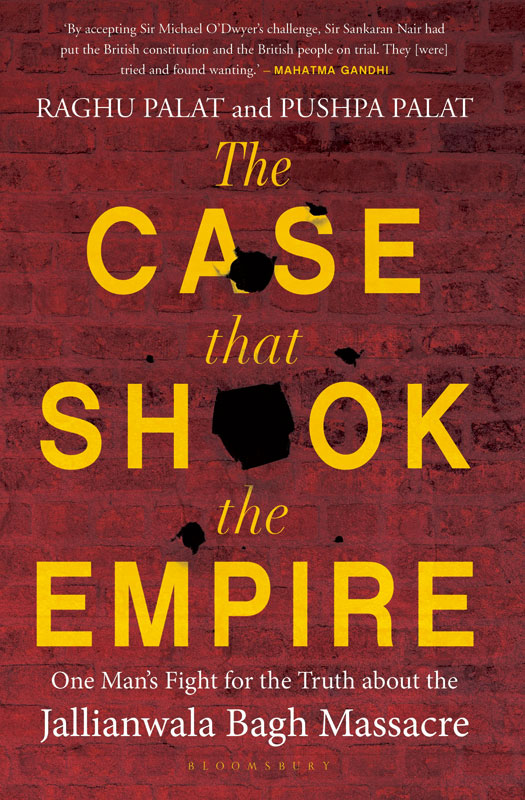

The

CASE

that

SHOOK

the

EMPIRE

The

CASE

that

SHOOK

the

EMPIRE

One Mans Fight for the Truth about the

Jallianwala Bagh Massacre

RAGHU PALAT and PUSHPA PALAT

BLOOMSBURY INDIA

Bloomsbury Publishing India Pvt. Ltd

Second Floor, LSC Building No. 4, DDA Complex, Pocket C 6 & 7,

Vasant Kunj New Delhi 110070

BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY INDIA and the Diana logo are trademarks of

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published in India 2019

This edition published 2019

Copyright Raghu Palat and Pushpa Palat, 2019

Raghu Palat and Pushpa Palat have asserted their right under the Indian Copyright Act to be identified as authors of this work

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers

The content of this book is the sole expression and opinion of its authors, and not of the publishers. The publisher in no manner is liable for any opinion or views expressed by the authors. While best efforts have been made in preparing this book, the publisher makes no representations or warranties of any kind and assumes no liabilities of any kind with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the content and specifically disclaims any implied warranties of merchant ability or fitness of use of a particular purpose.

ISBN: HB: 978-93-89000-27-6; eBook: 978-93-89000-29-0

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

Created by Manipal Digital Systems

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc makes every effort to ensure that the papers used in the manufacture of our books are natural, recyclable products made from wood grown in well-managed forests. Our manufacturing processes conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin.

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com and sign up for our newsletters

In worship, we dedicate this book to

the Lord Guruvayurappan,

who has always protected, guided and looked after us

and our family.

We wrote this book in order to introduce our daughters,

Divya and Nikhila, and our granddaughter,

Nivaya, to their familial roots.

H istory should be the mirror of time and life in its varied nuances. Sometimes frills and embroidery lace it, but sometimes there are voids, too. The book illumines one such void an epoch that has been the matrix of the development and growth of constitutional governance and rule of law in India. It deals with one of the greatest Indians of the modern era Sir Chettur Sankaran Nair.

A few words about this legendary figures contributions:

There is a little village called Mankara by the Nila River around which lores and legends live, where time stands still even today. Colonel Humberston, who was leading the British army against Tipu Sultan, makes mention of this village and an aristocratic family, Chettur Tarward, into which Sir Chettur Sankaran Nair was born in the year of the Mutiny of 1857. After his early years, he moved to Madras for his higher education. A brilliant man, he soon became a lawyer, a Member of the Legislative Council as well as the President of the Indian National Congress. He was the first Indian Advocate General of the Madras province, a judge in the High Court of Madras and a Member of the Viceroys Executive Council a position only second to the Viceroy, and one that had remained beyond the reach of an Indian.

While he was in the Council, the massacre of Jallianwala Bagh, a blot on history, took place. On a Baisakhi Day many patriotic Indians held a meeting in an enclosed space. When General Dyer reached there with a posse of men, he had the exits sealed and commanded his men to open fire. In the ensuing bloodbath, hundreds were killed and wounded. Later, Indians were subjected to many ignominies such as being made to crawl on roads and salute all Englishmen. Chettur Sankaran Nair was agitated by the British Governments highhandedness and he resigned the high office he held in protest, despite the pleas of leaders like Motilal Nehru, Mrs Annie Besant, C.F. Andrews and others, who requested him to remain in the Council and fight the system from within.

His finest hour, however, was yet to come. Nair went to England and carried his mission forward, fighting a case against the powerful Englishman ODywer in an English court and, in the course of his defence, convincing the British public including people like Winston Churchill about the barbarity of the British Government in India. Consequently, for the first time ever, the Indian freedom movement was discussed in the British Parliament when Ramsay McDonald was prime minister. This was a milestone.

Nair, however, had to pay dearly for his cause, as will be evident to the readers of this book by the end. He was truly the messiah of the freedom movement, not only of India, but also other British colonies. Indias constitutional development started with the 1919 Montagu Chelmsford Reforms which he influenced, and later the 1935 Act. His name will be written in letters of gold in the pantheon of history.

Justice Chettur Sankaran Nair

Kerala High Court

August 2019

A t the entrance to the library in my grandfather Ramunni Menon Palats mansion in Karkitamkunnu, in Palakkad District, Kerala, is a life-size portrait of my great-grandfather, Sir Chettur Sankaran Nair, in the regalia of a member of the Viceroys Executive Council. I had always been impressed by this striking portrait of a commanding, regal personality dressed in a dark blue velvet tailcoat embellished with a gold-embroidered stand collar and cuffs, white breeches, white stockings and black buckled shoes. In one hand, he held a cocked hat decorated with a gold lace loop, while the other rested on the hilt of a sword that swung from his hip.

Growing up, I had heard stories from my grandparents and my father about Sir. They spoke of him with awe and always referred to him as Sir. They seemed inordinately proud of this larger-than-life figure. I knew he had fought a case in England during the British rule, but did not delve deeper into his life at the time. Possibly in the hope of inculcating discipline in me, my grandfather would tell me about how disciplined Sir was in his habits. When he was a High Court judge in Madras, Sir would wake up at 4.30 a.m. every day. After his yoga and exercises, he would have his breakfast and leave for court. In the evenings, he would drive to the beach for a walk and then repair to the Cosmopolitan Club to read the papers. He would return home at around 6.30 p.m., bathe, spend some time reading sacred texts, eat at 8 p.m. and retire for the night.

On the other hand, my father would tell me of the times when Sir would visit the Hill Palace in Thripunithira, the capital of Cochin State, where my father was brought up. My grandmother, Ratnam Amma Palatt, was the older daughter of Sir Rama Varma, then Maharaja of Cochin. My great-grandmother, the Maharani, wanted her oldest grandson brought up at the palace. My father recalled the times when he would go to Sirs room early in the morning and find him doing a headstand, even at the age of 70, in the shirshasan yogic pose. Sir would tell him to join in. My father, not being particularly athletic, tried it a few times but failed quite miserably.

This discipline also extended to Sirs punctuality. He would reach the railway station at least an hour before a train arrived. This was despite the fact that the train would have waited for him, on account of his position, in the unlikely event of him turning up late. After all, it was because of him that the Viceroy, Lord Hardinge, ordered a station to be built at Mankara, his village in south Malabar, in 1915.