For my mother and father.

And in memory of my grandfather,

Ishwar Das Anand.

No guilt in survival.

I wish I could have told you that.

Vengeance and retribution require a long time; it is the rule.

CHARLES DICKENS ,

A Tale of Two Cities

PREFACE

In February 2013, David Cameron became the first serving British prime minister to visit Jallianwala Bagh, a stones throw from the Golden Temple in Amritsar. The dusty walled garden was the site of a brutal massacre on 13 April 1919 and, for Indians at least, it has come to represent the worst excesses of the Raj. On that day, a British officer, Brigadier General Reginald Dyer, hearing that an illegal political meeting was due to take place, ordered his men to open fire on around 20,000 innocent and unarmed men, women and children. The youngest victim was a six-month-old baby; the oldest was in his eighties.

The lieutenant governor of Punjab, a man named Sir Michael ODwyer, not only approved of the shootings, but spent much of the rest of his life praising the action and fortitude of his brigadier general. Sir Michaels attitude, coupled with the behaviour of British soldiers in the weeks that followed, created a suppurating wound in the Indian psyche. The scar is still livid in the north of India to this day.

The number of people killed at Jallianwala Bagh has always been in dispute, with British estimates putting the dead at 379 with 1,100 wounded and Indian sources insisting that around 1,000 people were killed and more than 1,500 wounded. By his own admission, no order to disperse was given and Dyers soldiers fired 1,650 rounds in Jallianwala Bagh that day. He instructed them to aim into the thickest parts of the crowd, which happened to be by the perimeter, where desperate people were trying to scale walls to escape the bullets. The configuration of the garden and the position of the troops meant civilians were trapped, much like fish in a barrel.

The bloodbath, though appalling, could have been so much worse. Dyer later admitted that he would have used machine guns too if he had been able to drive his armoured cars through the narrow entrance to the Bagh. He was seeking to teach the restive province a lesson. Punctuated by bullets, his message was clear. The Raj reigned supreme. Dissent would not be tolerated. The empire crushed those who defied it.

Ninety-four years later, laying a wreath of white gerberas at the foot of the towering red stone Martyrs Memorial in Amritsar, David Cameron bowed solemnly as India watched. In the visitors condolence book he wrote the following message: This was a deeply shameful event in British history one that Winston Churchill rightly described at the time as monstrous. We must never forget what happened here. And in remembering we must ensure that the United Kingdom stands up for the right of peaceful protest around the world.

Though sympathetic, Camerons words fell short of the apology many Indians had been hoping for. The massacre was indeed monstrous, and I have grown up with its legacy. My grandfather, Ishwar Das Anand, was in the garden that day in 1919. By a quirk of fate, he left Jallianwala Bagh on an errand minutes before the firing started. He remembered Brigadier General Dyers convoy passing him in the street. When he returned, my grandfather found his friends, young men like him in their late teens, had been killed.

According to his children, Ishwar Das Anand suffered survivors guilt for the rest of his relatively short life. In his late forties, he would lose his sight, but tell his sons never to pity him: God spared my life that day. It is only right that he take the light from my eyes. He never managed to reconcile why he had lived while so many others had not. He found it excruciatingly painful to talk about that day. He died too young. I never got the chance to know him.

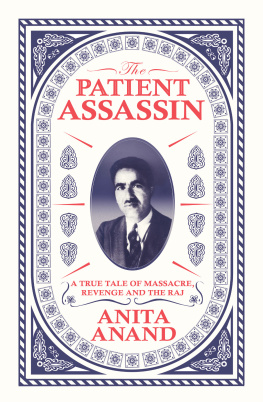

The story of Jallianwala Bagh is tightly wound round my familys DNA . Ironically, it is also woven into my husbands family history, a fact we only realised years into our marriage. His forebears were pedlars from Punjab who came to settle in Britain in the 1930s. Bizarrely, one of them found himself living with a man named Udham Singh. The happy-go-lucky Punjabi would turn out to be the Patient Assassin of this book, deified in India, the land of my ancestors, but largely unknown in Great Britain, the land of my birth.

Speaking to descendants of the pedlar community, which came to Britain in the early 1920s, helped me to understand their experience. They also helped to bring Udham Singh to life.

Thanks to my parents, I grew up knowing the names of Reginald Dyer and Sir Michael ODwyer, but of course Udham Singh loomed larger still. According to legend, he, like Ishwar Das Anand, was in the garden on the day of the massacre. Unlike my grandfather, he was not crushed by survivors guilt, but rather consumed by violent rage. We, like many Punjabis, were told how Udham, grabbing a clod of blood-soaked earth, squeezed it in his fist, vowing to avenge the dead. No matter how long it took him, no matter how far he would have to go, Udham would kill the men responsible for the carnage.

Twenty years later, Udham Singh would fulfil at least part of that bloody promise. He would shoot Sir Michael ODwyer through the heart at point-blank range in London, just a stones throw away from the Houses of Parliament.

The moment he pulled the trigger, he became the most hated man in Britain, a hero to his countrymen in India, and a pawn in international politics. Joseph Goebbels himself would leap upon Udhams story and use it for Nazi propaganda at the height of the Second World War.

In India today, Udham Singh is for many simply a hero, destined to right a terrible wrong. At the other extreme, there are those who traduce him as a Walter Mitty-type fantasist, blundering his way into the history books. The truth, as always, lies somewhere in between; Udham was neither a saint, nor an accidental avenger. His story is far more interesting than that.

Like a real-life Tom Ripley, Udham, a low-caste, barely literate orphan, spent the majority of his life becoming the Patient Assassin. Obsessed with avenging his countrymen and throwing out the British from his homeland, he inveigled his way into the shadowy worlds of Indian militant nationalism, Russian Bolshevism and even found himself flirting with the Germans in the run-up to the Second World War. Anybody dedicated to the downfall of the British Empire had something to teach him, and he was hungry to learn.

Ambitious, tenacious and brave, Udham was also vain, careless and callous to those who loved him most. His footsteps have led me on a much longer, more convoluted journey than I ever anticipated. The diversity of sources and need to cross-reference hearsay has been challenging, but not the hardest thing about writing this book. I have also had to consciously distance myself from my own family history. For a while, the very names ODwyer and Dyer paralysed me. We had been brought up fearing them.

Only when I thought of ODwyer as Michael, the ardent Irish child growing up in Tipperary, or Dyer as Rex, the sensitive boy who cried over a dead monkey he once shot by accident, could I free myself to think about them as men, and even start to understand why they did the things they did. It was the only way I could empathise with the situation they faced in 1919 and the years that followed.

![Anita Anand - The Library Book. Anita Anand ... [Et Al.]](/uploads/posts/book/40194/thumbs/anita-anand-the-library-book-anita-anand-et.jpg)