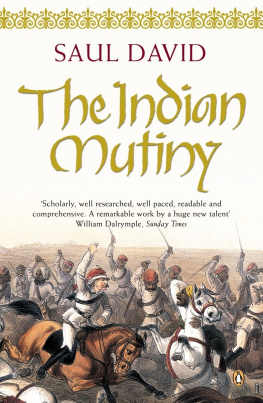

Julian Spilsbury - The Indian Mutiny

Here you can read online Julian Spilsbury - The Indian Mutiny full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2018, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Indian Mutiny

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:2018

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Indian Mutiny: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Indian Mutiny" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Indian Mutiny — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Indian Mutiny" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The Indian Mutiny

JULIAN SPILSBURY

Orion

First published in Great Britain in 2007

by Weidenfeld & Nicolson

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Julian Spilsbury 2007

Every effort has been made to contact the owners

of material reproduced in this book. Any omissions drawn to

the publishers attention will be rectified in future editions.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be

reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted,

in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior

permission of both the copyright owner and

the above publisher.

The right of Julian Spilsbury to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library.

eISBN 978 0 2978 5630 6

www.orionbooks.co.uk

So spoke Lord Canning, at the banquet given to him by the Court of Directors of the East India Company, prior to his departure for India to take up his post as Governor General. The Directors could be forgiven, in February 1856, when Canning took over from his predecessor, Lord Dalhousie, for thinking that his term of office would indeed be peaceful. The Honourable East India Company had arrived in India as traders in the seventeenth century, firstly in Madras, and later in Bombay - known as John Company or Kampani Bahadur to the natives (Bahadur being a title of respect implying courage). By the eighteenth century, with the anarchy that accompanied the decline of the Mogul Empire, the Company found itself fighting for survival against the French, and various native princes, themselves eager to profit from the weakening of the power of the Emperor at Delhi. To fight these wars the British relied largely on Indian troops - sepoys (from the Turkish sipahi , meaning soldier) - whom they trained on European lines, using European weapons. Wars for survival turned to wars of conquest. After Robert Clives victory at the Battle of Plassey in 1757, the British - in the form of the East India Company - gained Bengal, becoming, in effect, an Indian ruler, subject to the Emperor. Over the next hundred years the Company, by a combination of intrigue, negotiation, treachery and, when occasion demanded, brute force (this last provided by its sepoy army, backed by smaller numbers of British troops), had become rulers of most of India. The Mogul Emperor, formerly a puppet of Maratha princes, became a puppet of the British. By the 1850s the Company had ceased trading altogether and existed solely to run the civil and military affairs of India, as agents of the British Government. The Government had the final say in the appointment of the Governor General, who ruled the Bengal Presidency from Calcutta and exercised authority over the governors of the two other Presidencies - Madras and Bombay.

The latter are all Mohammedans and a considerable proportion of the Bengal cavalry are of the same race. The fact is, that with the exception of the Mahratta tribe, the Hindoos are not, generally speaking, so much disposed as the Mohammedans to the duties of a trooper; and though the Mohammedans may be more dissipated and less moral in their private conduct than the Hindoos, they are zealous and high-spirited soldiers, and it is excellent policy to have a considerable proportion of them in the service, to which, experience has shown, they often become very warmly attached.

Of the Bengal infantry he wrote:

They consist largely of Rajpoots, who are a distinguished race among the Khiteree, or military tribe. We may judge of the size of these men when we are told that the height below which no recruit is taken is five feet six inches. The great proportion of the Grenadiers are six feet and upwards. The Rajpoot is a born soldier. The Mother speaks of nothing to her infant but deeds of arms, and every action and sentiment of the future man is marked by the first impressions that he has received. If he tills the ground - which is the common occupation of this class - his sword and shield are placed near the furrow, and moved as his labour advances. The frame of the Rajpoot is always improved (even if his habits are those of civil life) by martial exercises; he is, when well treated, obedient, zealous and faithful.

A warning note comes from Albert Hervey, a captain in the Madras Army, writing only a few years later:

Treat the sepoys well: attend to their wants and complaints; be patient and, at the same time, determined with them; never lose sight of your rank as an officer; be the same with them in every situation; show that you have confidence in them; lead them well, and prove to them that you look upon them as brave men and faithful soldiers, and they will die for you. But adopt a different line of conduct - abuse them; ill-treat them; neglect them; place no confidence in them; show an indifference to their wants or comforts - and they are very devils!

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Indian Mutiny»

Look at similar books to The Indian Mutiny. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Indian Mutiny and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.