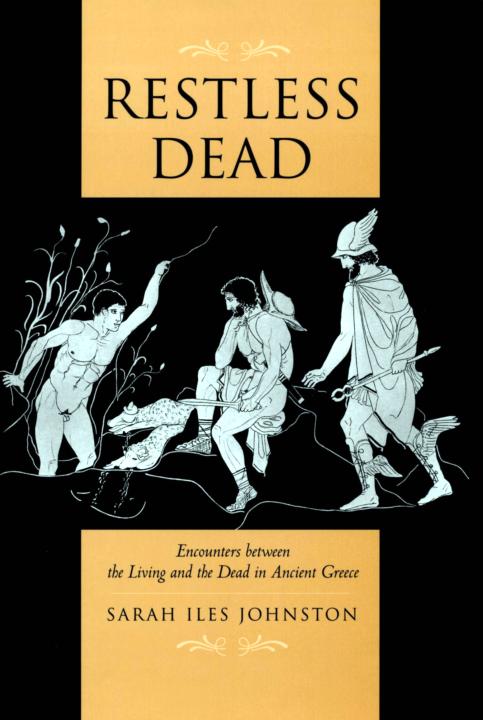

SARAH ILES JOHNSTON

vii

xv

xvii

xxi

PART I. A SHORT HISTORY OF THE DEAD IN ANCIENT GREECE

PART II. RESTLESS DEAD

PART III. DIVINITIES AND THE DEAD

Index Locorum

The Corinthian tyrant Periander sent his henchmen to the oracle of the dead to ask where he had lost something. The ghost of Periander's dead wife, Melissa, was conjured up but she refused to tell them where the object was because she was cold and naked-she said that the clothes buried with her were useless because they had not been burnt properly. To prove who she was, she told the men to tell Periander that he had put his bread into a cold oven. This convinced Periander, who knew that he had made love to Melissa's corpse after she died.

Periander immediately ordered every woman in Corinth to assemble at the temple of Hera. They all came wearing their best clothes, assuming there was going to be a festival. Periander then told his guards to strip the women naked and burn their clothes in a pit while he prayed to Melissa. Then Melissa's ghost told him where the missing object was.

The Greek historian Herodotus tells it to illustrate the moral flaws of a tyrant: to serve his own purposes, Periander was willing to rob and humiliate all the women in Corinth, to say nothing of indulging in necrophilia. But at the same time, Herodotus provides a textbook example of how relations between the living and the dead were supposed to work. We learn from the story that the dead demand proper funerals, which ought to include gifts that they can use in the afterlife. This afterlife must be similar to life itself, considering that clothing is de rigeur. The living, for their part, can expect the dead's cooperation, so long as they keep the dead happy. Transactions between the living and the dead can take place on home territory (Periander burns the clothing in Corinth), but special deals may be negotiated at a place such as the oracle of the dead, under the guidance of experts. Even then, one can't be too careful: to be sure that the ghost who appears is really the right ghost, one ought to have some sort of proof. Melissa's proof not only reveals Periander's personal proclivities but shows that she knows what has been happening in the upper world since she died, as does her knowledge of where Periander's lost object can be found. Finally, the story shows that dealing with the dead may become a civic concern even if their anger is caused by the act of a single citizen. It was Periander's failure to send Melissa to Hades with the proper wardrobe that made her mad, but it requires contributions from the whole female population to bring her around.

We find each of these ideas in other ancient Greek sources as well, but it is their assemblage that makes Herodotus's story fascinating, for it presents a paradox: it acknowledges that a person who once ate and drank and laughed with the rest of us is gone, but it also reflects the vigor with which she continues to inhabit the world of those who knew her. Because the dead remain part of our mental and emotional lives long after they cease to dwell beside us physically, it is easy to assume that they are simply carrying on their existence elsewhere and might occasionally come back to visit us. From this assumption arise a variety of hopes and fears. Hopes that the dead may aid the living, by revealing hidden information, by bringing illness to enemies, and by a variety of other favors-even by simply visiting those whom they have left behind:

Fears that the dead may somehow punish the living for the injuries or neglect they suffered, by bringing illness, by causing nightmares, or simply by refusing to cooperate when needed, as Melissa did.

The dead are very much like us, driven by the same desires, fears, and angers, seeking the same sorts of rewards and requiring the same sort of care that we do. For this reason, the world of the dead is not only a source of both possible danger and possible help, but a mirror that reflects our own. The reflection is frequently a distorted one, to be sure: the dead are often credited with remarkable powers, and thus manifest their desires, fears, and angers in ways that go beyond any available to us. But the distortion is not random: through their excesses, the dead reveal, like fingerprint powder shaken over a table, where desires, fears, and angers are most acute among the living.

Every detail in which a culture cloaks its ideas about the dead has the potential to reveal something about the living. The types of misfortune that a culture traces to the anger of the dead often reveal what that culture fears losing-and correspondingly values-the most, for blaming the dead can be a way of avoiding other explanations that would challenge the culture's social coherence or theodicy. If one were to blame the death of one's child on the witchcraft of one's neighbor, for instance, the relationship between one's own family and the family of the neighbor might be irreparably damaged. If one were to blame it on divine wrath, one would be forced to acknowledge either that one deserved to lose the child or that divinity was morally fickle. Tracing the child's death to the angry dead avoids all of these problems: the dead serve as convenient scapegoats, shouldering burdens of blame too heavy for other agents to carry. To take another example, many cultures believe that death under certain circumstances or before certain milestones of life have been passed will condemn the soul to become a restless ghost. Studying the conditions that produce these ghosts offers insight into what the culture considers, conversely, to constitute a full life and a good death.

There have been few attempts to apply them to materials from ancient Greece, however. This is all the more unfortunate because Greek literature abounds with incidents in which the living and the dead interact. Already in the Iliad and the Odyssey, ghosts appear to complain of poor treatment and demand that the living help them; tragedy, that most Greek of literary genres, frequently focuses on the dead, their problems, and the obligations that the living bear toward them. Students of Greek culture and literature have much to learn from the dead and yet have virtually ignored them.

I suspect that this neglect is due to a deep-rooted reluctance to accept the idea that the Greeks believed in the possibility of anything so "irra tional" as interaction between the living and the dead. This reluctance may seem remarkable, given that substantial advances have been made toward acknowledging and understanding other manifestations of supposed irrationality among the Greeks: the study of Greek magic, most notably, has attracted considerable interest in recent years. But, if one so chooses, magic can be presented as a technology, as something approaching our own concept of an "applied science," pace James Frazer. After all, it works by certain rules that our ancient sources claim have been "tested" and can be passed from teacher to student. Indeed, the very fact that there are teachers and students lends magic the look of a serious discipline. Moreover, magic is intensely concerned with power: the power of the magician over those whom he enchants and his power to persuade or compel deities and daimones to work his spells. And power in all of its incarnations and from all angles-who wields it, who submits to it, and why-is a topic that has always found a respectable place in classical studies.