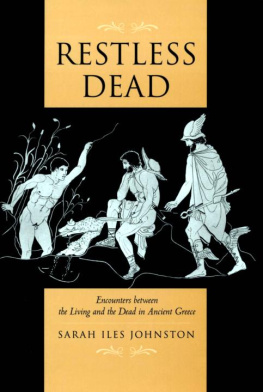

Restless Dead

Encounters Between the Living

and the Dead in Ancient Greece

SARAH ILES JOHNSTON

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS

Berkeley Los Angeles London

University of California Press

Berkeley and Los Angeles, California

University of California Press, Ltd.

London, England

1999 by

the Regents of the University of California

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Johnston, Sarah Iles, 1957

Restless dead : encounters between the livingand the dead in ancient Greece / Sarah IlesJohnston.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-520-21707-2 (alk. paper)

e-ISBN 978-0-520-92231-0 (ebook)

1. GhostsGreeceHistory. 2.GreeceReligion. I. Title.

BF1472.G8J64 1999

133.1'0938dc21

| 98-44365

CIP |

For Carole E. Newlands,

in friendship and admiration

Contents

1. :

Narrative Descriptions of the Dead

2. :

Rituals Addressed to the Dead

3. :

The Origin and Roles of the Gos

4. :

Dealing with Those Who Die Violently

5. :

Female Ghosts and Their Victims

6. :

How the Mistress of Ghosts Earned Her Title

7. :

Erinyes, Eumenides, and Semnai Theai

Prologue

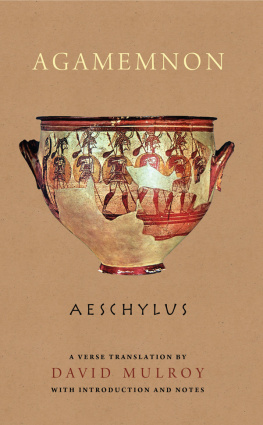

The Corinthian tyrant Periander sent his henchmen to the oracle of the dead to ask where he had lost something. Theghost of Perianders dead wife, Melissa , was conjured upbut she refused to tell them where the object was becauseshe was cold and nakedshe said that the clothes buriedwith her were useless because they had not been burnt properly.To prove who she was, she told the men to tell Perianderthat he had put his bread into a cold oven. This convincedPeriander, who knew that he had made love to Melissascorpse after she died.

Periander immediately ordered every woman in Corinthto assemble at the temple of Hera. They all came wearingtheir best clothes, assuming there was going to be a festival.Periander then told his guards to strip the women naked andburn their clothes in a pit while he prayed to Melissa. ThenMelissas ghost told him where the missing object was.

So goes one of our oldest ghost stories. The Greek historian Herodotustells it to illustrate the moral flaws of a tyrant: to serve his own purposes,Periander was willing to rob and humiliate all the women in Corinth, tosay nothing of indulging in necrophilia. But at the same time, Herodotusprovides a textbook example of how relations between the living and thedead were supposed to work. We learn from the story that the dead demandproper funerals, which ought to include gifts that they can use inthe afterlife. This afterlife must be similar to life itself, considering thatclothing is de rigeur. The living, for their part, can expect the deads cooperation,so long as they keep the dead happy. Transactions betweenthe living and the dead can take place on home territory (Periander burnsthe clothing in Corinth), but special deals may be negotiated at a placesuch as the oracle of the dead, under the guidance of experts. Even then,one cant be too careful: to be sure that the ghost who appears is reallythe right ghost, one ought to have some sort of proof. Melissas proofnot only reveals Perianders personal proclivities but shows that sheknows what has been happening in the upper world since she died, asdoes her knowledge of where Perianders lost object can be found. Finally,the story shows that dealing with the dead may become a civicconcern even if their anger is caused by the act of a single citizen. It wasPerianders failure to send Melissa to Hades with the proper wardrobethat made her mad, but it requires contributions from the whole femalepopulation to bring her around.

We find each of these ideas in other ancient Greek sources as well, butit is their assemblage that makes Herodotuss story fascinating, for itpresents a paradox: it acknowledges that a person who once ate anddrank and laughed with the rest of us is gone, but it also reflects thevigor with which she continues to inhabit the world of those who knewher. Because the dead remain part of our mental and emotional liveslong after they cease to dwell beside us physically, it is easy to assumethat they are simply carrying on their existence elsewhere and might occasionallycome back to visit us. From this assumption arise a variety ofhopes and fears. Hopes that the dead may aid the living, by revealinghidden information, by bringing illness to enemies, and by a variety ofother favorseven by simply visiting those whom they have left behind:by wandering into my dreams you may bring me joy, Admetus says tohis wife, Alcestis , as she lies dying, expressing hope that their love willsurvive death. Fears that the dead may somehow punish the living forthe injuries or neglect they suffered, by bringing illness, by causing nightmares,or simply by refusing to cooperate when needed, as Melissa did.

The dead are very much like us, driven by the same desires, fears, andangers, seeking the same sorts of rewards and requiring the same sortof care that we do. For this reason, the world of the dead is not only asource of both possible danger and possible help, but a mirror that reflectsour own. The reflection is frequently a distorted one, to be sure:the dead are often credited with remarkable powers, and thus manifesttheir desires, fears, and angers in ways that go beyond any available tous. But the distortion is not random: through their excesses, the dead reveal,like fingerprint powder shaken over a table, where desires, fears,and angers are most acute among the living.

Every detail in which a culture cloaks its ideas about the dead has thepotential to reveal something about the living. The types of misfortunethat a culture traces to the anger of the dead often reveal what that culturefears losingand correspondingly valuesthe most, for blamingthe dead can be a way of avoiding other explanations that would challengethe cultures social coherence or theodicy. If one were to blame thedeath of ones child on the witchcraft of ones neighbor, for instance, therelationship between ones own family and the family of the neighbormight be irreparably damaged. If one were to blame it on divine wrath,one would be forced to acknowledge either that one deserved to lose thechild or that divinity was morally fickle. Tracing the childs death to theangry dead avoids all of these problems: the dead serve as convenientscapegoats, shouldering burdens of blame too heavy for other agents tocarry. To take another example, many cultures believe that death undercertain circumstances or before certain milestones of life have beenpassed will condemn the soul to become a restless ghost. Studying theconditions that produce these ghosts offers insight into what the cultureconsiders, conversely, to constitute a full life and a good death.

The models that I have just sketched will be familiar to many readersbecause they are taken from well-known studies published earlier in thiscentury. Anthropologists who did fieldwork with tribal cultures at thattime recognized the contribution that analysis of mortuary rituals andeschatological beliefs could make toward constructing a picture of theway that those cultures worked; scholars of other cultures eventually beganto apply these models to their own materials as well. There havebeen few attempts to apply them to materials from ancient Greece, however.This is all the more unfortunate because Greek literature aboundswith incidents in which the living and the dead interact. Already in theIliad and the Odyssey, ghosts appear to complain of poor treatment anddemand that the living help them; tragedy, that most Greek of literarygenres, frequently focuses on the dead, their problems, and the obligationsthat the living bear toward them. Students of Greek culture andliterature have much to learn from the dead and yet have virtually ignoredthem.