Table of Contents

To Buntzie

... along with me...

A man will turn over half a library to make one book.

SAMUEL JOHNSON (1775)

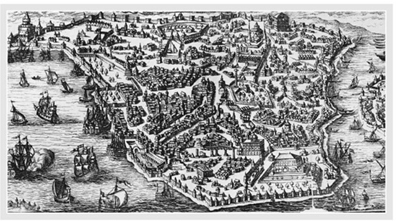

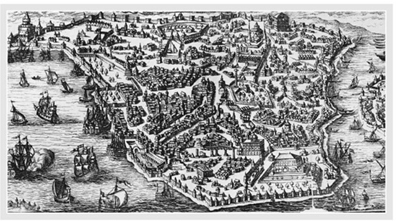

Map of Istanbul from Happelius, Die Kurze Beschreibung der Gantzen Turckey, 1688.

Preface

Toward the middle of the tenth century, an Arab geographer and cosmographer from the great city of Baghdad wrote an account of the known world in which he included a few words about some of the strange, wild people beyond the northwest frontier of civilizationthat is to say, of the Islamic empire of the caliphs. Of the northernmost of these peoples, he observed, Their bodies are large, their natures gross, their manners harsh, their understanding dull and their tongues heavy. Their color is so excessively white that it passes from white to blue.... Those of them who are farthest to the north are the most subject to stupidity, grossness and brutishness.

In 1798 an Ottoman secretary of state wrote a memorandum to inform the Imperial Council about the recent troubles in Paris. He began his description of the events which, in the West, came to be known as the French Revolution: The conflagration of sedition and wickedness that broke out a few years ago in France, scattering sparks and shooting flames of mischief and tumult in all directions, had been conceived many years previously in the minds of certain accursed heretics.... The known and famous atheists Voltaire and Rousseau, and other materialists like them, had printed and published various works, consisting... of the removal and abolition of all religion, and of allusions to the sweetness of equality and republicanism, all expressed in easily intelligible words and phrases, in the form of mockery, in the language of the common people.

During the nine and a half centuries that intervened between these two reports, the level of information about Europe among Middle Eastern visitors and observers had improved considerably. The basic attitudes of contempt and certitude, however, remained substantially unchanged. Much the same may be said about Western attitudes toward the Middle East. Though in general rather better informed, medieval and early modern Western observers of the Middle East, including travelers, show a similar self-satisfied ignorance in their discussions of the places they visited and the peoples they met.

The rise and spread of Islam brought the Middle East into contactand sometimes into collisionwith other regions and cultures: in the east with India and China, in the south with Africa, in the west and north with Christendom. The last of these, seen by Islam as its only serious rival both as world faith and world power, gave rise to the most sustained and most traumatic of these encounters. It began with the advent of Islam in the seventh century and the irruption of the Muslim Arabs into Palestine, Syria, Egypt and North Africa, all until then part of the Christian world. Three major areas of European Christendom were for a while lost to Islam: the two peninsulas at the southwestern and southeastern corners of Europe, Iberia and Anatolia, and the vast plains of Russia. The first was conquered and ruled by Arabs and Moors, the second by Turks, the third by Islamized Tatars. The loss of Anatolia proved permanent. The attempt by the Crusaders to reconquer the Holy Land failed. But in both Russia and the Iberian Peninsula, the Christian inhabitants were in time able to defeat and expel their Muslim rulers, and, in the flush of victory, even pursued them whence they had comefrom Russia to Asia, from Spain and Portugal to Africa and beyond. The reconquest grew into conquest and began the great expansion of Europe, from both east and west, which in time brought most of Asia and Africa into the European orbit.

The relationship between the Middle East and the West has not been limited to war and its consequencesfear and mistrust, resentment and hatred, and a readiness to invent and believe the most absurd of calumnies. As well as fighters and preachers, there were others who looked at the people beyond their religious frontier with sometimes puzzled, sometimes eager curiosity. By turns amused and bewildered, they reflected in their books and in their letters home a range of envy, respect, hostility andvery rarelyadmiration.

With the expansion of commerce during and after the crusades, European diplomats began to establish permanent missions in the coastal cities of the Ottoman Empire. Trained to observe and ready to comment on their hosts, their colleagues and (with deep mistrust) their interpreters, diplomats traveling in both directions provide some of the best accounts we have of the habits and customs of those with whom they were sent to negotiate. Merchants in the Middle East, as elsewhere, discussed commodities, prices and their competitors. European Christian merchants defied papal and national bans to sell arms to Saladin fighting the Crusaders and, centuries later, to the Turks advancing toward the heart of Europe. Constructive engagement has a long history.

European travelers in the East discovered such delights as coffee and polygamy. An Italian pilgrim in fourteenth-century Alexandria describes his joyous discovery of the banana; an Egyptian sheikh in nineteenth-century Paris describes the French postal system and observes how it is used, among other purposes, for assignations. Inevitably, there are more negative commentson the position of women, the punishment of crime, the conduct of war.

Much has been written of late about Western misperceptions, through negligence and prejudice, arrogance and insensitivity, and sheer lack of interest. Some have gone so far as to argue that Western views of the Middle East are largely the result of such attitudes and that misperception has frequently been aggravated by willful misrepresentation, serving a Western desire to dominate and exploit. Certainly, there is no lack of ignorance and prejudice in what Westerners, through the centuries, have written about the Middle East. But the same is true about much of what Middle Easterners have written about the West, in the phases of both their advance and their retreat.

Some territorial definition may be useful. The term Middle East has never been precisely demarcated and extends, for some purposes, as far west as Morocco. Broadly speaking, it applies to the countries of southwest Asia and northeast Africa, with vague and ill-defined extensions at both endsfrom Iran into Central Asia and beyond to the borders of China; from Egypt into Africa, westward to the Atlantic and southward up the Nile as far as the Islamic faith and the Arabic language predominate.

The words Europe and West, in common use in Europe and the West, were not in the past used in the Islamic Middle East, where West meant their own west, North Africa and for a while Sicily and Spain. The term Europe occurs very infrequently, in a few translations of Greek geographical works. These regions and their inhabitants were usually designated either by religious termsinfidels, pagans, Christiansor by ethnic termsGreeks and Romans in the adjoining Mediterranean lands, Slavs and Franks in eastern and western Europe.

For a long time, the peoples of Europe used similar designations, referring to their southern and eastern neighbors by religious terms, as infidels or Mohammedans, or by ethnic terms, as Moors, Saracens, Turks and Tatars. The terms Near East and Middle East came into general use at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Clearly, they reflect a view of the world from a Western vantage pointmore specifically, from Western Europe, then rapidly extending its rule, and to an even greater extent its influence, in the rest of the Old World.

Next page