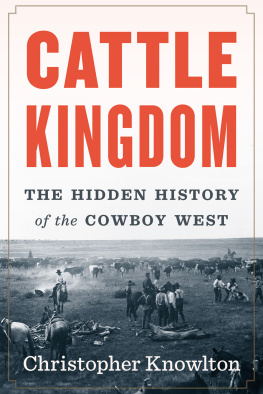

Copyright 2017 by Christopher Knowlton

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

www.hmhco.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 978-0-544-36996-2

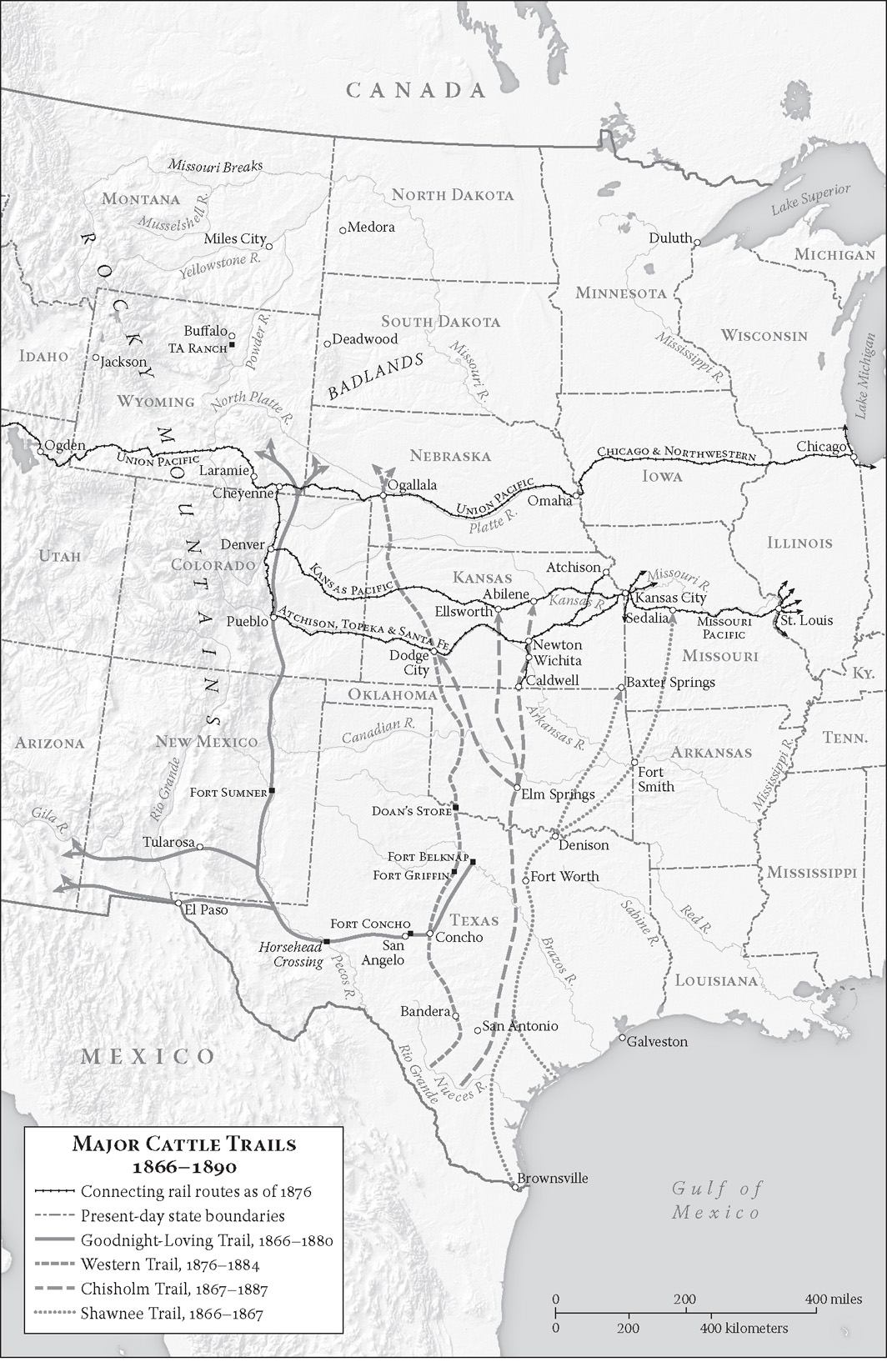

Map by Mapping Specialists, Ltd.

Illustration credits appear on .

Cover design by Brian Moore

Cover photograph: A Roundup at the Ja Ranch W. D. Harper/Library of Congress/Getty Images

Author photograph Stacey J. Byers, Captured Spirit Photography

e ISBN 978-0-544-36997-9

v1.0517

For Pippa

To be a cowboy was adventure;

to be a ranchman was to be king.

Walter Prescott Webb,

The Great Plains

Introduction

Throughout the summer and fall of 1886 a series of puzzling natural occurrences unfolded on the open range of the American West. In the Dakotas, Montana, and Wyoming, the sky turned so hazy at times that a pale halo formed around the sun. Exceptionally dry and hot weather sparked prairie brushfires that burned out of control. Elsewhere, hatches of grasshoppers, known as Rocky Mountain locusts, grew into deafening swarms and ate the little grass that was available.

John Clay, the Scottish-born manager of the Cattle Ranch & Land Company, rode out to inspect the Wyoming rangeland, taking the old pony express route through Lost Soldier and Crooks Gap: There was scarce a spear of grass by the wayside. We rode many miles over the range. Cattle were thin and green grass was an unknown quantity except in some bog hole, or where a stream had overflowed in the spring. It was a painful sort of trip. There you were helpless. There was no market for young cattle, your aged steers were not fat, and your cows and calves were miserably poor. He could not shake a sickening sense of foreboding.

Lincoln Lang, a rancher in the Badlands, noticed that beavers were furiously at work on the walls of their lodges and piling up unusual quantities of saplings for winter food. Others observed that the winter coats of the elk and the moose grew in thick and heavy. Birds, especially the cedar waxwings and the Canada geese, flocked and migrated south a full six weeks earlier than normal.

Over in Montana, the veteran trail driver E.C. Teddy Blue Abbott noticed snowy owls perched in the Douglas firs and paused on his horse to examine them from a distance. In his sixteen years on the open range, he could not recall ever having seen one before.

Teddy Blues boss, the cattle baron and former gold miner Granville Stuart, noticed the owls too. One local Native American tribal leader wagged his finger at Stuart and warned him that the birds were the ghostly harbingers of a harsh winter to come.

The cattlemen were already grumpy. Beef prices had been in sharp decline for several years now, which had prompted many of the cattle operations to take fewer steers to market. That meant there were more cattle on the already overstocked open range. The problem was compounded when a presidential order, signed by Grover Cleveland in July of the prior year, forced the cattle herds off the giant Cheyenne and Arapaho Indian Reservation, which encompassed most of Colorado and the lower portion of Wyoming. The cattlemen drove many of those herds, comprising some 210,000 head of cattle, onto the northern ranges and then moved them from valley to valley, like the pieces on a giant checkerboard, in an effort to find the little remaining grass and water available in areas still free of the suddenly ubiquitous barbed wire.

Many of the veteran cattlemen had grown rich during the boomthe greatest agricultural expansion the country had ever seen. But there were worries that they had overexpanded and overleveraged themselves to keep abreast of the rapidly evolving industry. By some accounts, total investment in the cattle industry now exceeded the capitalization of the entire American banking system. By other accounts, Cheyenne, Wyoming, the epicenter of the boom, had the highest median per capita income in the world. Many of the countrys richest families and individualsMarshall Field, the Rockefellers, the Vanderbilts, the Flaglers, the Whitneys, the Seligmans, and the Ameseswere now cattle investors.

The open range was crowded with speculators and new money and giant cattle conglomerates. At the Cheyenne Club, the posh watering hole of the cattle barons, there were whispers about lax management, overcounting of cattle herds, even the questionable solvency of some of the larger outfits. One of the most prominent members, a former president of the club named Hubert Tesche-macher, had actually resolved that fall to liquidate his ranch at a loss, to the consternation of his Boston and New York investors. Another club member, Moreton Frewen, a Sussex squire who founded the first joint-stock cattle company registered in England, arrived in town after a year away and wrote to his wife how quiet Cheyenne seemed. It was as though its boomtown businesses, anticipating some calamity, had come to a momentary standstill.

Twenty-eight-year-old Theodore Roosevelt, who had just completed his third year as a cattle entrepreneur in the Dakota Territory, displayed a shrewd understanding of the situation when he wrote that fall, in an article for The Century Magazine, In our country, which is even now getting crowded, it is merely a question of time as to when a winter will come that will understock the ranges by the summary process of killing off about half of all the cattle through-out the North-west.

His assessment would prove accurate.

A week before he left the Dakotas to return to New York via the Northern Pacific Railroad, Roosevelt said goodbye to his two best hired men, Bill Sewall and Sewalls nephew Wilmot Dow, who had managed the Elkhorn Ranch for him. The two men had decided to return east with their wives to their native Maine. Sewall had argued from the outset that the Badlands were unsuitable rangeland for cattle. Roosevelt had contradicted him and now would pay the price.

A short time later Roosevelts Badlands neighbor, the Frenchman known as the Marquis de Mors, departed for Paris, as he did every fall, leaving behind his towering slaughterhouse and immense beef-packing plant, by far the largest plant west of Chicago, a monument that matched his own ambition and ego. Although he wouldnt admit it to a local reporter, who had heard rumors and questioned him at the train station, his empire was teetering on the brink of insolvency.

The first snowstorm arrived in November, followed in December by a gale-force blizzard that would last for three days. Granville Stuart was caught on a stagecoach between Musselshell and Flat Willow when the second storm hit. The visibility was so poor that he and the other passengers took turns walking in front of the team of horses with a lantern to guide them.

In January a brief thaw arrived, accompanied by a warm wind known as a chinook, but the thaw served only to melt the snow enough to create a thick crust when the cold returned, which it did, with conviction, a few days later. The next storm lasted for ten full days. The temperature dropped to an excruciating twenty-two below zero Fahrenheit and kept falling, to twenty-eight below, to thirty below, and finally, on January 15, to forty-six below zero. Over in the Dakotas the temperature reached sixty degrees below zero in places and remained there. The snow was so fine that it stung the face. Whipped by the wind, it pushed through crevices and under doorsills and left little piles as fine as the sand of an hourglass.

Next page