Table of Contents

A TEXAS COWBOY: OR, FIFTEEN YEARS ON THE HURRICANE DECK OF A SPANISH PONY

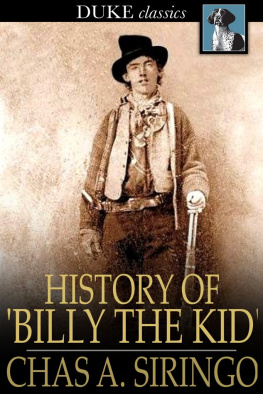

Charles Angelo Siringo was born in Matagorda County, Texas, in 1855. After a nomadic boyhood, he signed on as a teenage cowboy for the noted cattle king Shanghai Pierce. Later, as a cowboy detective for the Pinkerton Agency, he spent two decades chasing outlaws, infiltrating radical unions, and hunting down murderers. He was an acquaintance of the notorious gun-slinger Billy the Kid. He died in Hollywood in 1928.

Richard W. Etulain is Professor of History and director of the Center for the American West at the University of New Mexico. A specialist in the history and literature of the American West, he has authored or edited more than thirty-five books. He also edits eight series of publications on the American West and recent U.S. history. Among his recent publications are Re-imagining the Modern American West: A Century of Fiction, History, and Art (1996); Portraits of Basques in the New World (coeditor, 1999); Does the Frontier Explain American Exceptionalism (editor, 1999); Telling Western Stories: From Buffalo Bill to Larry McMurtry (1999); and The Hollywood West (coeditor, 2000). Professor Etulain is past president of both the Western Literature and Western History associations. He is currently at work on a biography of the legendary westerner Calamity Jane.

INTRODUCTION

Charlie Siringo lived life at a gallop. After a nomadic boyhood, he signed on as a teenage cowboy for the noted cattle king Shanghai Pierce. Later, as a cowboy detective for the famed Pinkertons Agency, he spent two decades chasing outlaws, infiltrating radical unions, and hunting down murderers. Even in his last decades Siringo kept on the move, ranching, consulting, and hanging out with movie cowboys in Hollywood.

Yet even this high-speed, frenetic life allowed Siringo time to write. In 1885, after he had retired from cowboying and had become a merchant in Kansas, he published his first book, A Texas Cow Boy or, Fifteen Years on the Hurricane Deck of a Spanish Pony. Sensationally successful in sales, this classic account of cowboying prepared the way for Siringos five later books dealing with his experiences on the open range and as a Pinkerton detective. A man of abundant energy and courage, Siringo lived a chock-full life and put his personal brand on written accounts of his intriguing life.

A Texas Cowboy sold remarkably well. First issued in 1885 by M. Umbdenstock and Company, a Chicago printer, Siringos cowboy autobiography reappeared the next year in a second edition (the edition in hand), with a thirty-page addendum. Within the next decade, Rand, McNally and Company issued another inexpensive version of Siringos first book. On the eve of the World War I, J. S. Ogilvie published still another cheap paper edition. Although Siringo may have exaggerated in claiming that A Texas Cowboy sold nearly a million copies, sales were at least several hundred thousand.

What has attracted so many readers to A Texas Cowboy and kept it nearly continuously in print for more than a century? The subject matter? Undoubtedly. The authors knack for story-telling? Clearly. The notoriety of cowboys and the outlaw Billy the Kid? Obviously. The pull of a Wild West that intrigued so many Americans in the late nineteenth century? Surely. The attractions were several, and they continue to this day.

Siringos popular account of his early range life also appealed to thousands of readers because it conveyed the kind of story they had come to anticipate about the West. From the frontier exploration narratives and James Fenimore Coopers Leather-stocking novels of the early nineteenth century to the dime novels, Local Color stories, and Wild West shows of the second half of the century, audiences expected lively western stories, full of adventure, action, and courageous characters. From beginning to end, Siringos A Texas Cowboy fulfills these expectations.

Siringos story falls into four divisions. The first chapters detail his carefree boyhood on the Texas coast and his early experiences in the upper Midwest and along the Mississippi. The second section commences with his early-teen experiences as a cowboy and his first trips up the Long Trail. The final chapters treat Charlies work on huge west Texas ranches and his pursuit of Billy the Kid and cattle thieves in New Mexico. The original version (1885) ended with Charlies marriage and his new job as a cigar and ice cream merchant in Caldwell, Kansas. This revised edition (1886) added a fourth section, a thirty-page, tongue-in-cheek discussion of the costs of raising cattle and horses and the frequent mistreatment of cow ponies on Texas ranches.

Charlie Siringo probably devoted little thought to the organization of his story. Instead, in A Texas Cowboy, as well as in nearly all of his later writings, Charlie serves as a campfire story-teller, spinning yarns about his range experiences. One anecdote quickly leads to another. Although Siringo seems driven to tell what happened in his boyhood, his early cowboy days, and during his pursuit of Billy the Kid, he shows scant interest in considering the significance of these pell-mell events.

Yet Charlies dozens of stories, strung together like so many notches on a pistol grip, tell much about Siringo and cowboy life on the southern plains. Charlies life followed a familiar pattern. Because of the early death of his father and the chaos of the Civil War, the youthful Siringo lived a wandering, nomadic life, gathering up experiences like a carefree Huck Finn of the cow country. Narrating these preadolescent years two to three decades after their occurrence, Charlie speaks of incessant activity, punctuated with numerous moves, boyhood jobs, hunger, and journeys to new places. Nothing lasts very long. Charlie lands a job for a few days or even attends school for a space of weeks, but conflicts with other boys, bosses, and teachers launch him on the road again. Restless and undisciplined, Charlie wanders up and down the Mississippi and then returns to his home near the Texas coast.

Even before he becomes a teenager, Charlie has learned to ride, to round up the mavericks (unbranded cattle) that roam through nearby plains and thickets. Then, as a sixteen-year-old, he signs on with the famed Abel H. (Shanghai) Pierce, whose Rancho Grande spread along the Gulf Coast country. Here, Charlies narrative overflows with descriptions of cow country matters. Rounding up wild steers, riding a rough string of half-wild ponies, and trying to catch enough sleep in the saddleall these and other tales crowd Charlies pages.

If one squeezes these early experiences on the open range and on the trail north, they reveal a good deal about Charlie Siringo. First of all, he had trouble sticking with any job. Crowd Charlie some or show him another job with more adventureor better payand he rode away with the new outfit. He had even more difficulty keeping his wages. After earning $114 as his share for skinning hundreds of dead cattle, Siringo, admitting that he never had so much money in all [his] life, immediately bought a $27 saddle. Earlier, a months paycheck went for a fancy pistol, the next, or at least part of it, for a pair of star topped boots and all of the balance on monte, a Mexican game. Throughout these early cowboy years, Charlie was singularly successful in living beyond his income. His taste for gaudy clothes and expensive gear and his itch to gamble, especially in bucking a game of monte, were his financial ruin. Without saying why, Charlie tells us he grew restless and that even among his friends no one knew where [he] was going.