Title Page

THE HAPPIEST DAYS OF THEIR LIVES?

Nineteenth-century education through the eyes of those who were there

by

Marion Aldis

and

Pam Inder

Publisher Information

Published in 2016 by

Chaplin Books

1 Eliza Place

Gosport PO12 4UN

Tel: 023 9252 9020

www.chaplinbooks.co .uk

Digital edition converted and distributed by

Andrews UK Limited

www.andrewsuk.com

Copyright 2016 Marion Aldis and Pam Inder

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in any retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright holder for which application should be addressed in the first instance to the publishers. No liability shall be attached to the author, the copyright holder or the publishers for loss or damage of any nature suffered as a result of the reliance on the reproduction of any of the contents of this publication or any errors or omissions in the contents.

The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Chaplin Books or Andrews UK.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the following people and institutions for their help:

Gavin Beetham (Thurlaston School), Barbara Bender, Birmingham University Special Collections, the Branscombe Project, Mrs June Bruxner-Randall and family, J J Heath Caldwell, Cumbria Record Office, Derbyshire Record Office, Harrow School Archive, Leicestershire Record Office, Mrs I Nicholson, Norfolk Record Office, Jean and Martin Norgate, Norwich Millennium Library, the late Averil Scott Moncrieff, Humphrey and Judy Scott Moncrieff, Colin and Joyce Shenton, John and Sue Sneyd, Staffordshire Record Office, Mark Stephens and the Stephens family, Marjorie and John Taylor and the Wigton Old Scholars Association (WOSA).

Sources of Illustrations

Ancestry.co.uk, Birmingham University Cadbury Research Library Special Collections, the Branscombe Project, Mrs June Bruxner-Randall and family, Debenham History Society Devonia, Harrow School Archive, Hastings Museum, J J Heath Caldwell, Leicestershire Record Office, Margaret Maidment History of Handmade Lace, Mrs I Nicholson, Norfolk Record Office, Jean and Martin Norgate, Popular Science Monthly 1875-6, Royal Collection, Mark Stephens and the Stephens family, WOSA. Other images came from Wikimedia Commons, and many are in private collections or are the authors own photographs.

Notes on Money

It is never possible to be entirely accurate when converting historical prices to their modern equivalents. The figures below are based on the conversion tables provided by National Archives and give some idea of the changing value of 10 worth of early twenty-first century money at various points in the nineteenth century.

1800 321.70

1810 339.60

1820 419.20

1830 494.90

1840 441.00

1850 585.30

1860 431.60

1870 457.00

1880 483.10

1890 598.90

1900 570.60

Notes on Quotations

The various diarists recorded dates in different ways at different times, as the mood took them - Sep/Sept/September 2/2 nd /second and so on. For consistency and ease of reading we have recorded all dates in full (eg September 2 nd ) and to a standard format. Similarly, punctuation has been added to some entries to make them easier to read.

Introduction

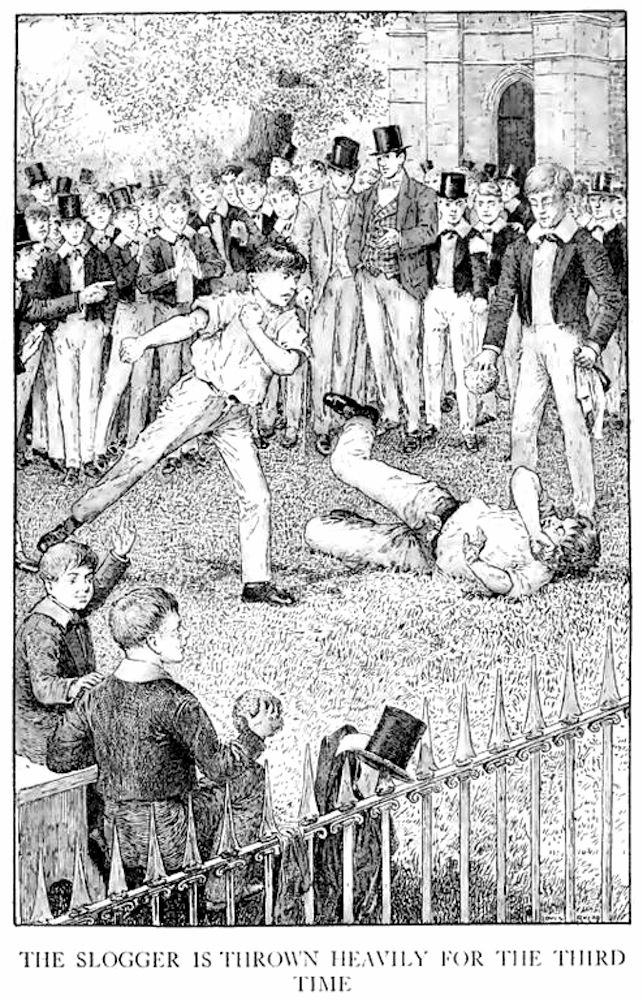

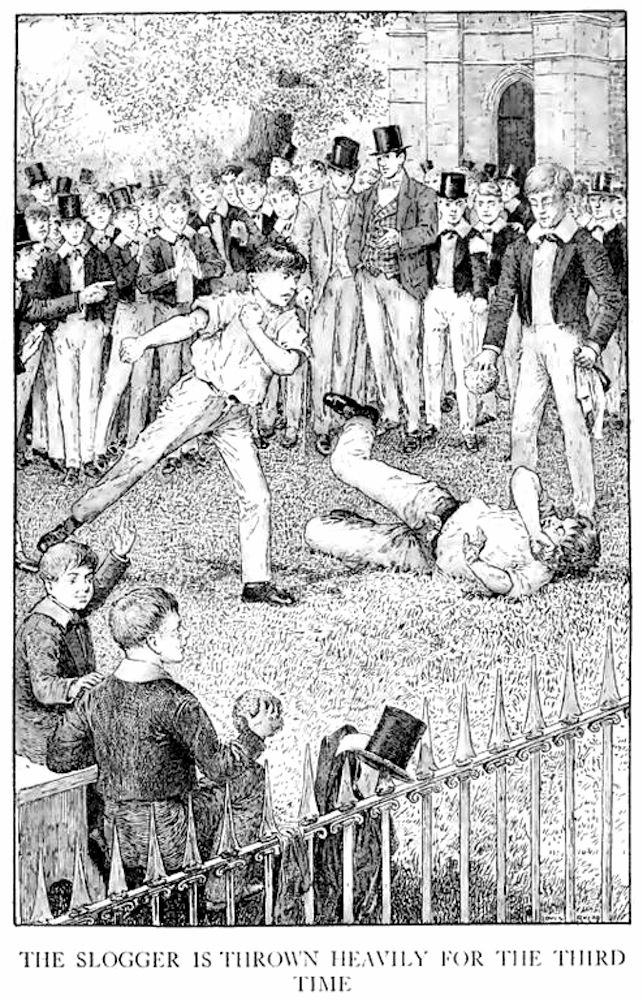

For many people, the words nineteenth-century schooling conjure up memories of Tom Browns Schooldays, Lowood School in Jane Eyre or Dotheboys Hall in Nicholas Nickleby . They may well also bring to mind sadistic schoolmasters in gowns and mortarboards ever ready to give their charges a vicious caning, little boys in top hats and Eton jackets, uncontrolled bullying, Latin tags and learning-by-heart, little girls in white pinafores meticulously stitching away at samplers, and the smell of chalk and ink. Although there are elements of truth in this jumble of images, there are also many misconceptions.

Illustration by Louis Rhead from Tom Browns Schooldays, 1911

Our particular interest is in diaries, and for the last twenty years we have been studying the diaries and personal papers of nineteenth-century women. We soon came to realise that original accounts often showed a very different picture to that generally portrayed. In the beginning our interest was sparked by a lady who recorded in her diary in the 1860s that she had just bought some stocks and shares in the newly built Canadian and Indian railways. A married woman buying stocks and shares in the mid-nineteenth century? Surely not? But she did. Until the Married Womens Property Acts of 1870 and 1882, everything a woman owned when she got married, except her clothes and personal belongings, became her husbands. She could own property in her own name but she could not administer it or sell it without her husbands consent. But women were inventive and, like our buyer of railway shares, they found ways to have some say in their lives despite the limitations the law placed on them.

We found that even working women were not completely subordinate to their menfolk. There were, for example, women like Sarah Bromley who worked as a paintress in the Staffordshire potteries; she married in 1812 but abandoned her drunken husband several times, leaving him for good in 1836, and raised her younger children with the money she earned herself - despite the fact that the law said it belonged to him. And such resourceful women were not as unusual as one might suppose.

As social historians we had thought we knew a lot about women in the nineteenth century but found a good deal that contradicted accepted wisdom. In the course of our research, we came across some childrens letters and diaries - and we wondered whether, on closer examination, they would throw a similar beam of light on to nineteenth century education. So we started looking.

***

One of our first discoveries was the dubious quality of the education for which apparently intelligent and caring parents were willing to pay good money.... I believe that water is 2 kinds of air and that there are several kinds of earth those are called elements which cannot be analysed there are 46, wrote Ann Marsh Caldwell in 1805. She was fourteen. Her education at home was a complete rag-bag of anything her tutors came up with on any given day - from how to grow peaches in Kentucky to the arcane workings of the French lottery.

Gerald Upcher, who went to Harrow School, recorded in his diary in 1858, This evening I went to a lecture given by Mr J Baker about the Philosophy of Water. It was very interesting ... he showed us some pretty experiments. . The theory was obviously still alive and well and being disseminated at Harrow in the 1850s.

A decade later, over in Norwich, little Fred Hibgame, along with twenty or more six- and seven-year-old boys, were having the three Rs beaten into them by a woman uneducated and bigoted even beyond her class at that period - and their parents were paying her for the privilege.

By 1800 most upper- and middle-class families regarded education as important. And they had a wide range of options. Their sons could go to one of the major public schools like Eton or Harrow or Rugby, or to one of their lesser known - but cheaper - imitators. Sensitive children could be home-schooled by tutors or sent to a school that was run in the home of a private individual. Many clergymen augmented their salaries in this way. Early schooling for boys was often in a dame school, frequently run by a spinster or widow in her own home. Girls sometimes went to such schools for the whole of their education, or were taught at home by a governess or by visiting tutors. There was no regulation of the private sector and teachers were not necessarily well-educated or compassionate; for some it was the only job open to them and they disliked and resented the children in their charge. Equally, there were others who were wise and inspirational, loved and fondly remembered by their pupils.

Next page