Acknowledgments

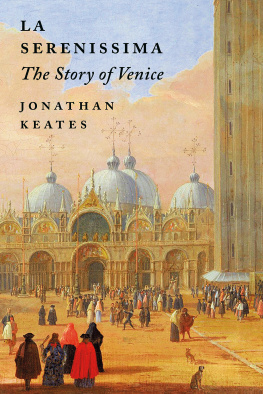

For valuable corrections and suggestions, I am deeply grateful to the Renaissance scholars who read and criticized the manuscript: Rona Goffen, Edward Muir, John OMalley, S.J., and Anthony Hecht read parts and asked probing questions. I also thank the proprietor of the best bookstore in Venice (Libreria Sansovino), Cesare Zanini, who was always ready to hunt down a needed volume for me; the staff of the hotel Monaco and Grand Canal, for many years of wonderful service; and Carla. My editors, Alice Mayhew, and her associate Anja Schmidt, worked assiduously with the researcher on art reproductions, Natalie Goldstein. My agent, Andrew Wylie, and his assistant, Zoe Pagnamenta, were supportive, as ever.

ALSO BY GARRY WILLS

Papal Sin

A Necessary Evil: A History of American Distrust of Government

Saint Augustine

John Waynes America: The Politics of Celebrity

Certain Trumpets: The Call of Leaders

Witches and Jesuits: Shakespeares Macbeth

Lincoln at Gettysburg: The Words That Remade America

Under God: Religion and American Politics

Reagans America: Innocents at Home

Nixon Agonistes

The Kennedy Imprisonment

Inventing America

Cincinnatus: George Washington and the Enlightenment

Explaining America

Lead Time

Chesterton

Politics and the Catholic Freedom

Roman Culture

Jack Ruby

The Second Civil War

Bare Ruined Choirs

Confessions of a Conservative

At Buttons

GARRY WILLS is the author of twenty-one books, including the bestseller Lincoln at Gettysburg (winner of the 1992 Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Critics Circle Award), John Waynes America, Certain Trumpets, Under God, A Necessary Evil, and Venice: Lion City, which was a Los Angeles Times Book Prize finalist. A frequent contributor to many national publications, including The New York Times Magazine and The New York Review of Books, he is also an adjunct professor of history at Northwestern University and lives in Evanston, Illinois.

WASHINGTON SQUARE PRESS

WASHINGTON SQUARE PRESS

www.SimonandSchuster.com

CHAPTER ONE

Contract with Mark

W HEREVER YOU TURN , in Venice, lions strut or lurk, colossal or miniature, placid or menacing. Entering the city from the Basin (Bacino) as diplomats did in the Renaissance, you pass between two high columns on the Piazzetta by the Doges Palace. One is topped, mysteriously, by a man standing on a crocodile that has a dogs head. The other has the citys famous emblem, a bronze lion with its wings spread for takeoff, its paws already dancing on the ground. It may not look so large, up there on its pillar, but it measures fifteen feet from the tip of its muzzle to the end of its tail and five feet from its perch to the small of its back. Viewed from the balcony of the Doges Palace, or from the ground with opera glasses, it reveals its natty mustache over a leering grin, its opaque white eyes, its intricately curled manenot a lion one wants to be on the wrong side of. It has an exotic history. Restorers decided in the 1980s that the bulk of its body is roughly 2,300 years old. The city it guards is a newcomer to this veteran, who has seen empires rise and fall, but has spent his last 850 years at this sentinel post (with only a brief time of Napoleonic captivity in France).

Proceeding deeper into the Piazzetta, one sees more accommodating lions, carved in relief on the faade of the Doges Palacetwo of them, facing in opposite directions, align their backs as a throne for a personified Venice as Justice, who holds in her hands a sword and the scales of judgment. The same configuration can be seen high up on the campanile at the left end of the Piazzetta. And across from it, on the right side of the Piazzetta, a winged lion stands in majestic profile over the formal entry to the Doges Palace. This is a religious lionit props up an open book with its right front paw, displaying the words, Rest here, Mark, my evangelist.lion heads projecting from the carved surface. There are also lion heads between the arches all down the long colonnade of the Doges Palace, as well as over the arches of the Library facing the palace.

Leaving the Piazzetta, one does not leave the lions behind. Go to the Arsenal, where Venice built its famous ships, and you find exotic lions on its front lawncaptured animals brought from Greece, kenneled here. Other lions project from the Arsenals gates or decorate its flag-pole base. Go to St. Marks Distinguished Brotherhood (Scuola Grande di San Marco), now a hospital, where lions carved in low relief by the Lombardo family guard the door. Cross to the nearby island of Murano, you will find a casually sprawling lion carved in relief on a little bridge. In the Church of St. Francis at the Vineyard, a very philosophical lion, painted by Tiepolo, peers down at you from the roof of a chapel. Out on the walkway near the Danieli Hotel there are monstrous lions, ten times life size, cast in bronze. One is gnawing at chains that have bound it for a time. (A cat sunning itself on the lions glistening back does not notice the discomfort of its oversize relative). Above almost every altar in the city there is a lion in one of the quadrants of the vault.

THE LION AS EVANGELIST

The churchy lion is the father of all the other felines in Venice. Its pedigree is even longer than that of the lion on the Piazzettas pillar. That creature dates from Cilicia in the third or fourth century before the common era ( B.C.E .). The lion of the altar vaults dates back to Babylonia of the sixth century B.C.E ., where Ezekiel saw a vision of Gods chariot-throne, guarded by four creatures. Each of the creatures had four faces, directed toward the symbolic four directionsfaces of a man, a lion, an ox, and an eagle (Ezekiel 1.10). This vision was adapted and simplified in the book of Revelation, where the four creatures are, respectively, a man, an ox, a lion, and an eagle (Rev 4.7). They became symbols of the apocalyptic end of the world (like the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse in Rev 6.117) and then of the entire body of revelation leading up to that ultimate fulfillment.

Since the four Gospelsof Matthew, Mark, Luke, and Johnwere considered the greatest revelation of Gods purpose in the world, their authors, the four evangelists, became associated with the four creatures of Revelation. Theologians found ways to show that the four symbols were appropriate for the beginnings of each gospel. Matthew was linked with the man for his supposed interest in human history, Mark with the lion for his opening desert scene, Luke with the ox for his implied reference to Isaiahs ox at the manger, and John with the eagle for his soaring hymn to the Logos of God. These are the symbols painted in the quadrants over each altar, as witnesses to the mystery they wrote about. They stand, as well, at key places like the mosaic in the dome of St. Marks basilica that is nearest the altarwhere Mark-as-lion is saturnine and vaguely anthropomorphic ( D 1.43).

So the lion is in Venice because of Mark. But why is Mark there? Venice did not exist during the time of Jesus, when Mark wrote his gospel. Several cities that did exist then had a better claim to connection with Mark, who was supposed to have spread the faith in themRome first, where legend had him writing his gospel; then Aquileia, on the Venetian lagoons terraferma, where Mark was supposed to have ordained the first patriarch (Saint Hermagoras); then Alexandria, where he founded a church and was martyred. Even Grado, near Aquileia, had a claim prior to Venices, since that is where the patriarchate of Aquileia was transferred in the sixth century. All Venice could boast was that, as part of the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of Aquiliea/Grado, it had a proximity to a Marcan realm.

WASHINGTON SQUARE PRESS

WASHINGTON SQUARE PRESS