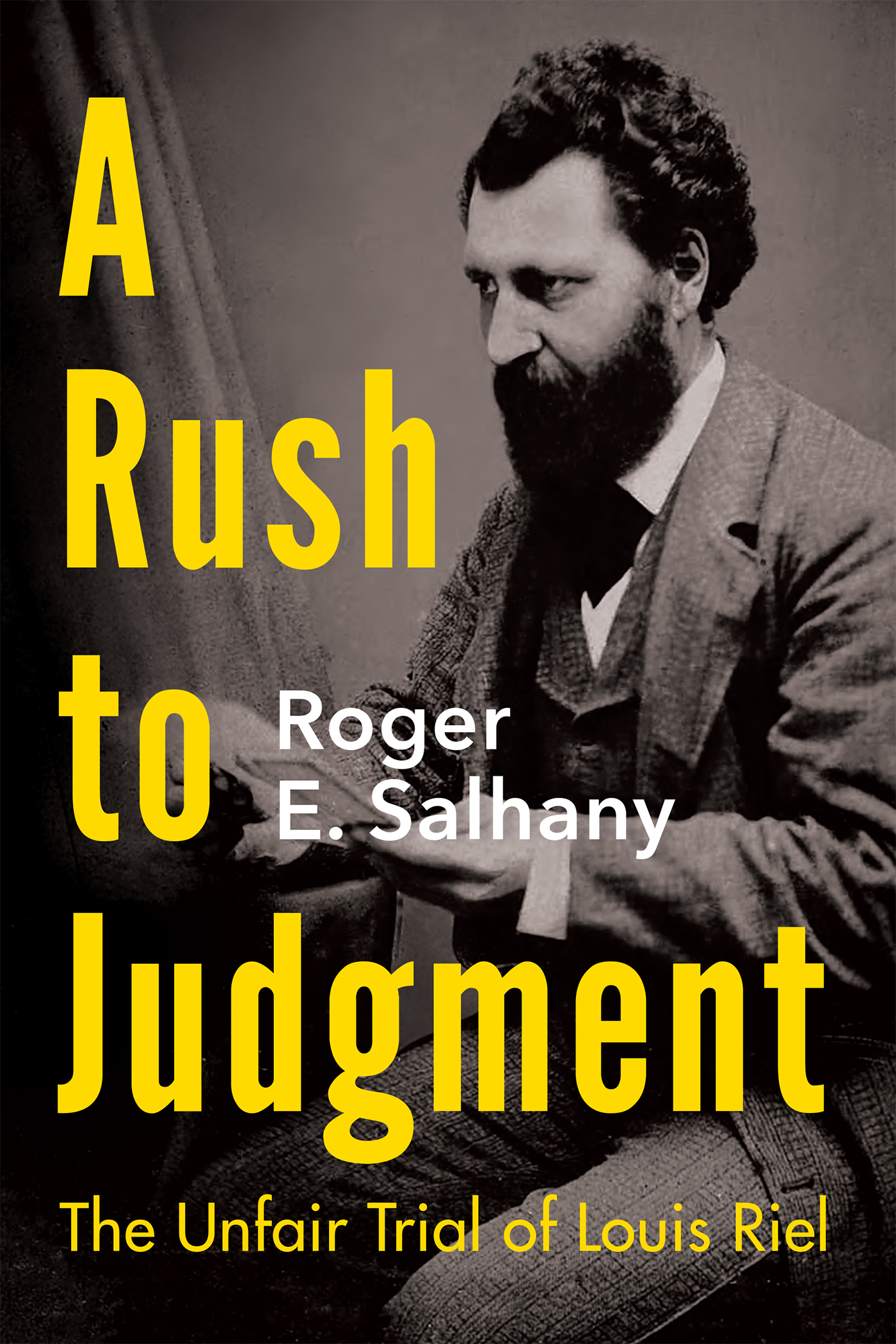

Copyright Roger E. Salhany, 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise (except for brief passages for purpose of review) without the prior permission of Dundurn Press. Permission to photocopy should be requested from Access Copyright.

Publisher: Scott Fraser | Editor: Laurie Miller

Cover designer: Sophie Paas-Lang

Cover image: Library and Archives Canada, R5768-2-5-F.

Printer: Webcom, a division of Marquis Book Printing Inc.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Title: A rush to judgment : the unfair trial of Louis Riel / Roger E. Salhany.

Names: Salhany, Roger E., author.

Description: Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20190196130 | Canadiana (ebook) 20190196157 | ISBN 9781459746091 (softcover) | ISBN 9781459746107 (PDF) | ISBN 9781459746114 (EPUB)

Subjects: LCSH: Riel, Louis, 1844-1885Trials, litigation, etc. | LCSH: Trials (Treason)CanadaHistory19th century. | LCSH: Riel Rebellion, 1885.

Classification: LCC KE228.R54 S22 2019 | DDC 345.71/0231dc23

We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council for our publishing program. We also acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Ontario, through the Ontario Book Publishing Tax Credit and Ontario Creates, and the Government of Canada.

Care has been taken to trace the ownership of copyright material used in this book. The author and the publisher welcome any information enabling them to rectify any references or credits in subsequent editions.

The publisher is not responsible for websites or their content unless they are owned by the publisher.

Printed and bound in Canada.

VISIT US AT

dundurn.com

dundurn.com

@dundurnpress

@dundurnpress

dundurnpress

dundurnpress

dundurnpress

dundurnpress

Dundurn

3 Church Street, Suite 500

Toronto, Ontario, Canada

M5E 1M2

You shall inherit hours which are replaced,

The earth won back, the trustier human ways

From history recovered, on them based

An amplitude of noble life.

John Pudney, The Dead

Over and above the question whether the evidence supports the conviction is the question whether the trial is being conducted by an unprejudiced Judge who understands the limits of the judicial function and understands his sworn duty to conduct the case within the limits of its issues.

Mr. Justice Bora Laskin in dissent in Regina v. Bevacqua and Palmieri, January 22, 1970

Contents

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

At ten oclock sharp on Tuesday, July 28, 1885, the trial of Louis David Riel for treason against Her Majesty Queen Victoria began in a small, makeshift courtroom on the ground floor of a rented two-storey brick building in downtown Regina. The province of Saskatchewan had not yet been created and Regina was a small prairie town in the North-West Territories. Although criminal trials at the time were usually conducted at the barracks of the North-West Mounted Police, the barracks were considered too cramped for a trial of this importance. Journalists from all parts of Canada and prominent local citizens had gathered to witness the trial. To accommodate everyone, including the lawyers, the jury and the various court officials, the offices of a land company had been rented.

That day was a typically hot and dusty dry summer day on the Prairies. Reporters, lawyers, and officials had arrived in Regina from around the world to watch the biggest trial in Canadian history. All of the participants in the trial and the spectators were packed into the sweltering fifty-foot by twenty-foot airless room. The trial lasted five days, ending in the late afternoon of Saturday, August 1, 1885. At 2:15 p.m. on that day, Judge Hugh Richardson, after a long charge to the jury, which he had begun on the previous day, sent the jury of six men out to the jury room to deliberate. After only an hour, they returned with their verdict. Francis Cosgrove, the foreman, rose to announce it.

Guilty.

But Cosgrove was not finished. He had a message for the judge from his fellow jurors: Your Honor, I have been asked by my brother jurors to recommend the prisoner to the mercy of the Crown.

The law required Judge Richardson to ask Riel if he had anything to say as to why the sentence of the court death by hanging, which was the only sentence for treason should not be pronounced upon him.

Louis Riel had a great deal to say. Yes, your Honor but before he could speak, one of his lawyers, Charles Fitzpatrick, interrupted Riel to ask the judge to note the objections Riels lawyers had already made at the beginning of the trial to the jurisdiction of the court to try Riel. The judge said that he would do so. Riel then asked, Can I speak now?

Oh yes, Richardson replied.

Riel knew that it would be the last time that he would ever be able to speak in a public forum to the people of Canada. He was anxious to justify to them why he had led his Mtis people against the government in a rebellion that had just been crushed by the Canadian Army. He had sent letters to the prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald, asking for a trial before the Supreme Court of Canada so that he could explain to the Canadian public his reasons for the Mtis rebellion, but his letters had gone unanswered. Now, if he was going to die, he wanted to die with honour and dignity. He began, Your Honors, gentlemen of the jury, but was interrupted by Judge Richardson, who reminded him that there is no jury now, they are discharged.

Riel responded with an unusual comment: Well, they have passed away before. Riel, who had studied law, must have known that the jury had been discharged after they had rendered their verdict. His answer is puzzling.

Instead of inquiring what Riel had meant, Judge Richardson, anxious to bring an end to the trial and deliver the sentence, simply agreed: Yes, they have passed away.

Riel quickly responded: But at the same time I consider them yet still there, still in their seats.

It was unlikely that Riel was speaking about the jury of six men that had just found him guilty of treason. He was probably speaking about the jury of Canadian citizens to whom he had sought to justify his actions from the first day the trial began. He had addressed the jury in the courtroom the day before, when the judge had finally allowed him to speak from the prisoners dock for the first time during his trial. In a long, rambling address, he had denounced his lawyers attempts to paint him as a lunatic who did not appreciate the nature of his actions. Although the law in 1885 did not allow an accused to give evidence as a sworn witness from the witness box, the judge had allowed him to speak to the jury as an unsworn witness from the prisoners dock. It would be eight more years before Canadian law would abolish this ancient and illogical obstacle that prevented an accused from answering his accusers.

dundurn.com

dundurn.com @dundurnpress

@dundurnpress dundurnpress

dundurnpress dundurnpress

dundurnpress