Table of Contents

PENGUIN BOOKS

THE ORACLE

William J. Broad is a senior writer at The New York Times and with colleagues there has twice won the Pulitzer Prize, as well as an Emmy. For decades, he has covered science topics ranging from biology and geology to astronomy and nuclear arms, writing hundreds of front-page articles. He is the author or coauthor of six books, most recently Germs: Biological Weapons and Americas Secret War , a number one New York Times bestseller. His books have been translated into more than a dozen languages and his work is featured in The Best American Science Writing 2005. He holds a masters degree in the history of science from the University of Wisconsin and lives with his wife and three children in the New York City suburbs.

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto,

Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi - 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), cnr Airborne and Rosedale Roads, Albany,

Auckland 1310, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published in the United States of America by The Penguin Press,

a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. 2006

Published in Penguin Books 2007

Copyright William J. Broad, 2006

eISBN : 978-1-440-64845-8

http://us.penguingroup.com

For Tanya, my Oracle

The greatest blessings come by way of madness, indeed of madness that is heaven-sent.

Socrates on the Oracle of Delphi

Art TK

Temple of Apollo

Art TK

Temple of Apollo

Prologue

HIS BOOK IS ABOUT a voice from the remote past that has come back to question the metaphysical assumptions of our age, to urge us to look beyond the claims of science and reexamine our attitudes toward spirituality, mysticism, and the hidden powers of the mind. The Oracle of Delphi has prompted this kind of reassessment before, starting three millennia ago, and, as improbable as it seems, is doing so again. Her message challenges some of the most basic tenets of our day, suggesting that we have deluded ourselves into thinking we know more than we really do.

Her own life evoked high purpose and what appeared to be superhuman powers. The Oracle was no single person but a sisterhood of mystics that spoke on behalf of the god Apollo to answer questions, give advice, and make prophesies. Her voice carried far. From Athens to the Greek colonies scattered throughout the Mediterranean to the distant kingdoms of Lydia and Egypt, people credited her with godlike accomplishments, saying she could not only predict the future with remarkable precision but read minds and see events far away, even ones carefully hidden from view. Her reputation as a social catalyst was just as great. She set Socrates, arguably the most celebrated philosopher of all time, onto the path of his lifes inquiry. And her moral influence helped the Greeks learn to revere oaths, human life, and the line between right and wrong.

The Oracle is back today because a team of American scientists managed to uncover one of her greatest secrets and, in the process, to restore her reputation and voice. It turns out that she got high.

The ancients alluded to this possibility, claiming that the Oracle regularly inhaled a sacred pneuma to prepare for communing with the gods and speaking on their behalf to mortals. But in modern times, armies of scholars could find no evidence of fumes or vapors and over the course of a century came to doubt the ancient claims and the honesty of the Oracle herself. Some ridiculed her as a fraud. Then the Americans took up the question. Carefully examining the ruins of the temple of Apollo at Delphi, analyzing rock and water, faults and landforms, working patiently for decades, the scientists discovered stark evidence that the Oracle had in fact inhaled a mist of intoxicating fumes, a mixture of potent gases that could promote trancelike states and aloof euphoria. It turned out that cracks in the bedrock had let powerful vapors rise into the temple, helping send the Oracle into her mystic ecstasies.

Getting high would seem to have little to do with illuminating the foundations of metaphysics or questioning the tenets of our age. But in this case it does. Moreover, the finding is not fleeting and ephemeralnot a drug miragebut grounded in a serious examination of the methods of science and the nature of true knowledge. The Oracles secret, it turns out, harbors what is possibly her ultimate gift.

This book tells that story, doing so in chronological order. The first chapter considers the Oracle in antiquity. The second tells of the rediscovery of the high priestess in the late nineteenth century and her eventual discrediting. The third through sixth chapters detail the detective story, telling how a team of four American scientists discovered the intoxicating fumes and how their finding established the reality of the ancient claims, bringing the Oracle back to life as a serious historical figure. And the last chapter discusses how that discovery lays bare the metaphysical assumptions of our day.

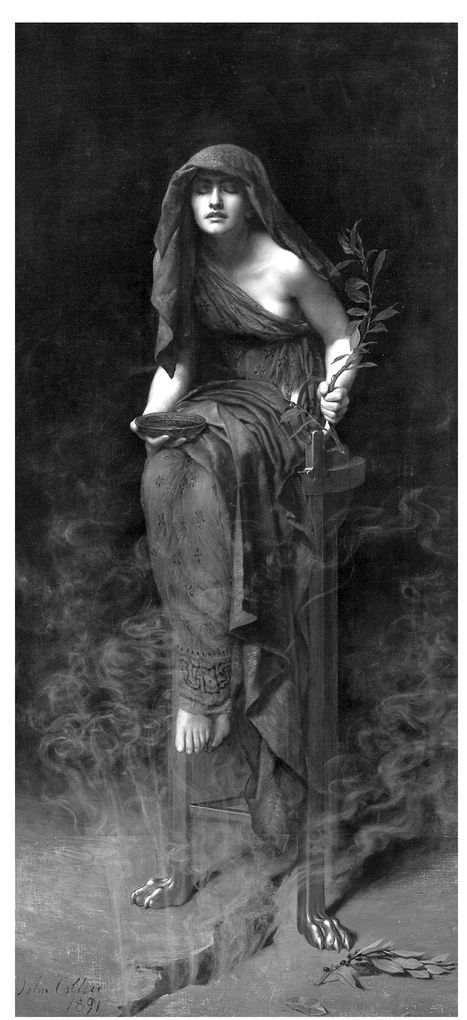

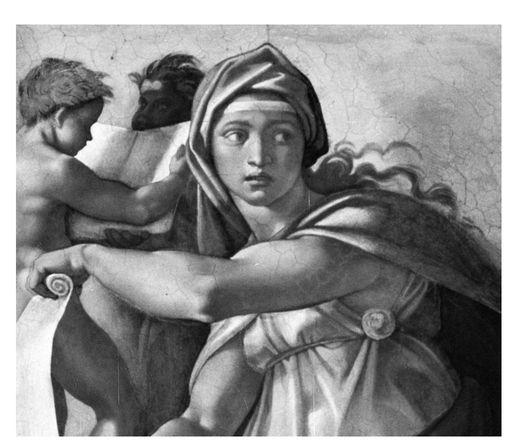

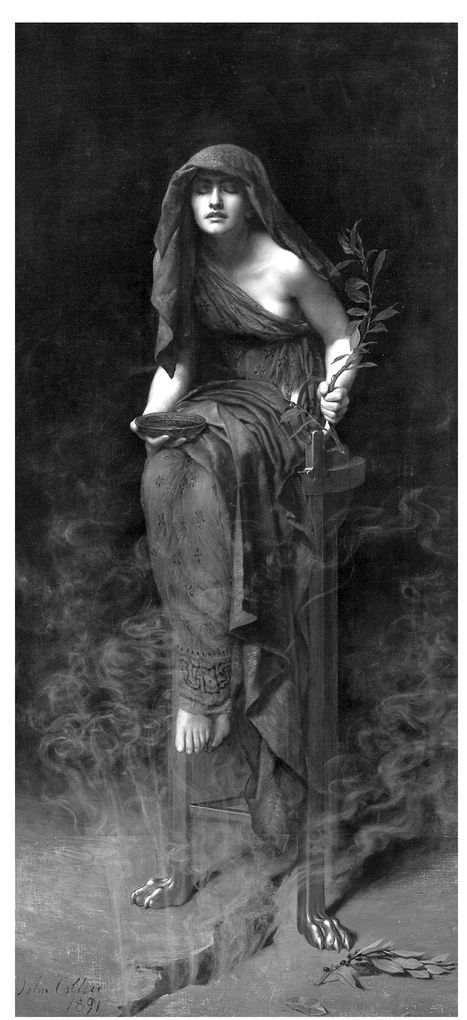

Michelangelo painted a pensive Oracle on the ceiling of the

Sistine Chapel. His chaste priestess contrasts with more

recent portrayals of her as sexually alluring.

The origins of this book go back to August 2001 when I read one of the teams reports and first learned of the fume discovery. Back then, what excited me was the scientific challenge to a century of scholarship, not the Oracle. Of her I knew little. Only much later did I find out about her connection to Socrates and that Michelangelo had given her a place of honor on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel as one of the seers who foretold the coming of Christ. Moreover, as a science writer and newspaperman steeped in traditions of skepticism, I was inclined to dismiss reports of her psychic abilities. The discovery of the fumes seemed to show that her prophetic visions were no more real than the hallucinations of any drug addict, her acclaim no more significant than any example of group illusion or wishful thinking.

The first surprise came before I went to Greece, which I had long admired but never visited. As an undergraduate, I had studied ancient Greek philosophy and mythology as a complement to my science curriculum, and as a graduate student I had specialized in the history of science, reading the early Greek thinkers who pioneered what became the scientific view of the world. They were my heroes, these fierce rationalists. Now I learned that the Greeks also revered the occult, consulting hosts of sibyls and psychics, seers and augurs, diviners and soothsayers. This hubbub coincided with the rise of Eastern philosophies that stressed an acceptance of fate, of karma. Not the Greeks. They constantly sought to know the future, to outwit the gods, to wage war on destiny. Nothing had prepared me for the existence of this mystic industry and the vast competition it presented to the Oracle. The old, somewhat obscure literature describing it bristled with amazing facts. Aristotle himself, it turned out, had authored a theory of telepathy. It was like discovering that Einstein had moonlighted as an astrologer.