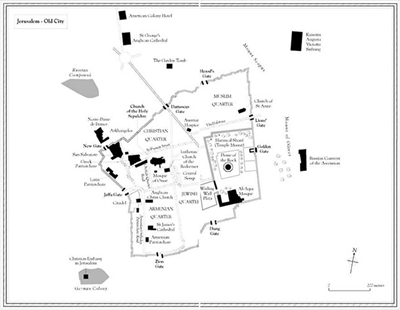

My first meeting with Father Athanasius Macora, OFM in 2000 and his description of the Church of the Holy Sepulchres eco-system were the initial inspirations for this book. I owe him and many others in Jerusalem a great debt of thanks for taking the time and trouble to talk to me.

A special thank you goes to Bishop Theophanis at the Greek patriarchate for finding me ideal lodgings with Rahme and Nasra in Arkhangelos. The friendship of these three people and that of George Hintlian means that Jerusalem feels like a second home to me now.

Anna Maria Boura, a Greek friend, put me in contact with Bishop Theophanis via two Greek diplomat friends of hers. A heartfelt thank you goes to her and to various other friends Bruce Clark, Sarah Cole, Broo Doherty, Father Alan Walker, Andrew and Cynthia Sparke, Dan Perry and James Meek for services ranging from providing steady encouragement and holidays, to reading and commenting on the text. More grateful thanks go to my agent David Godwin, editor Georgina Morley and her assistant Kate Harvey for all their help, encouragement and patience.

But my greatest debt of all is to the countless historians, pilgrims, travel writers and journalists whose works I have used. The task of spanning seventeen hundred years of history would have been impossible to contemplate without their earlier endeavours.

PREFACE

One hot, still afternoon in West Jerusalem a police helicopter circled deafeningly above an empty main street lined with hundreds of Israeli soldiers and a few dozen curious bystanders.

It was early autumn 2001 and, because Al-Qaeda had recently attacked New York and Washington and many in Europe believed that the war on terror could only be won by securing a peace between Israelis and Palestinians, I guessed we were about to witness a peace demonstration. The appearance of the first column of marchers and an accompanying din of bells, shrieking whistles and hooting shofars forced me to guess again.

More celebration than demonstration, this was parade rather than protest. One after another, groups of folk dancers, musicians and cheerleaders passed me. No one looked angry or outraged and not one of the banners mentioned Palestine or peace. One declared OHIO LOVES JERUSALEM, the next ALASKANS FOR ISRAEL ! Men in fancy dress with happy grins on their faces were breaking ranks to shake the hands and slap the backs of any black-suited Orthodox Jews they passed. Women scattered sweets and kisses among the children who were watching all those Americans and British in red and white and blue ensembles, Austrians in dirndls and lederhosen, Brazilians in bright yellow baseball caps strolling by, smiling and laughing and shouting Shalom! More banners passed, proclaiming ISRAEL YOU ARE NOT ALONE and BRITISH CHRISTIANS LOVE ISRAEL . An amplified Israeli voice thanked Indonesian, Estonian and Guatemalan Christians, and Australian and Swedish and Spanish Christians for coming all this way.

Like most of the Israeli witnesses of that event I knew far less about passionate Christian love for modern Israelis than I did about passionate Christian hatred traditionally displayed towards Jews as Christ-killers. Like most of them I was mistrustful, but also interested. Back in London I would uncover two salient facts about a brand of Christianity now known as Christian Zionism. First, it is a branch of Protestant fundamentalism whose roots lie deep in sixteenth-century Puritan England. Second, its modern adherents firmly oppose any resolution of the ArabIsraeli conflict that would grant the Palestinians a viable independent state.

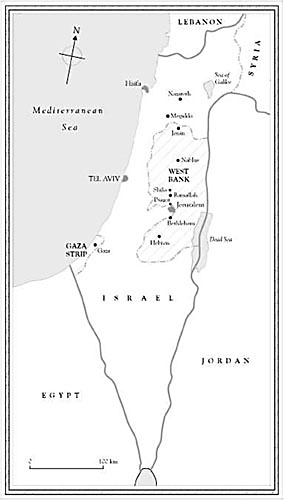

Christian Zionists believe that to acknowledge the Palestinians claim to this land between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River is to defy the will of God as expressed in the Bible. An extreme position and one naturally resented by Palestinians, it is also only shared by the estimated 15 to 20 per cent of Israelis who might be described as fundamentalists. In fact, the only obvious difference between the beliefs of these Christian fundamentalists and those of their Jewish counterparts is the identity of the messiah they are waiting for. The Jews expect a stranger, the Christians their saviour, Christ.

Christian Zionism has been flourishing since the biblically prophesied creation of Israel in 1948 and the Israeli capture of East Jerusalem in 1967, wherever love of the Scriptures is strongest and wherever Christian Zionists have travelled and evangelized, in South America, the Far East and Africa. But the United States is its heartland. In Americas Bible Belt, communities of Christians who, in the words of Donald Wagner, author of Anxious for Armageddon and professor of religion and Middle Eastern studies at Chicagos North Park University, see the modern state of Israel as the fulfilment of biblical prophecy and thus deserving of political, financial and religious support, are proud to rename their region Israels safety belt. More importantly, by stridently promoting the most extreme and uncompromising Israeli position, Christian Zionists are destroying their countrys usefulness and credibility as an impartial arbiter in the dispute, to say nothing of imperilling Israels future.

But todays American Christian Zionist is only the most recent variety of foreign Christian to take an intense and active interest in the Holy Land. Christians of all nationalities and denominations have been involving themselves in, or taking charge of, affairs in that remote corner of the Middle East for almost two millennia. The grand total of 450 years when Christian powers actually ruled the region turns out to be an inaccurate measure of the influence they have exerted there since the fourth century when Emperor Constantine the Great espoused Christianity and proclaimed a Roman legion garrison town on the road to nowhere the pilgrimage centre of the Christian world. The later race for wealth and empire and, still later, the greed for oil and influence has only intensified a fascination rooted in a deep love for the land where Jesus Christ lived and died and rose again.

The story of that long fascination is perhaps best told from Jerusalem because the past is ever present there, in its stones and in the minds and hearts of its inhabitants. On six separate visits to the city between the spring of 2002 and autumn 2003 I lodged with Arab Christians in a former monastery and mostly consorted with Christians, immersing myself in Jerusalems Christian past while observing its Christian present. I have not set out to record the centre-stage struggle between the Israelis and Palestinians for the right to occupy the Holy Land and nor have I attempted a comprehensive history of Christianity in the region. Rather, my aim has been to trace the parts played by a succession of outside Christian powers Byzantines, Crusaders, Italian princes, French and Spanish kings, Russian, German and Austrian emperors, and more recently British and American governments in the creation and maintenance of the planets most intractable conflict.

My argument is that fourth-century Byzantine Orthodoxy and twenty-first-century American Christian Zionism are two ends of a single long continuum in the eyes of many non-Christians. Three years on from 11 September 2001 it seems more urgent than ever that we in the traditionally Christian West begin to see ourselves as others see us.