Edited by

MAURICE KEEN

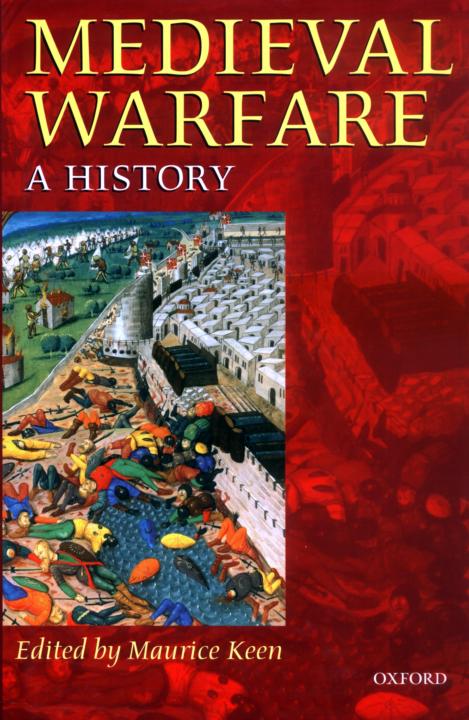

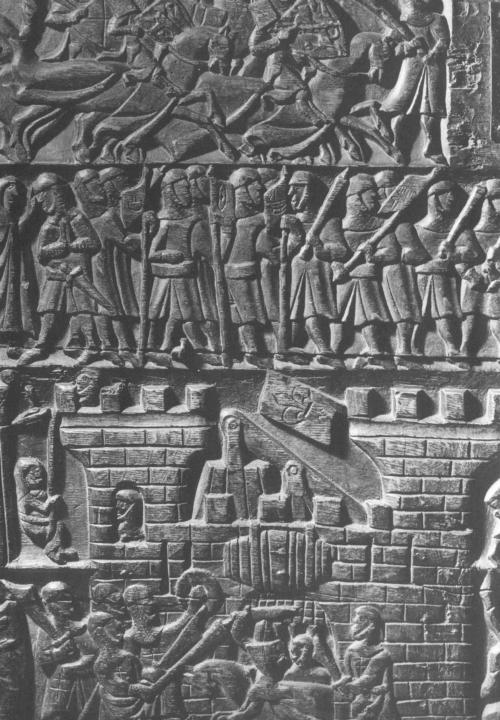

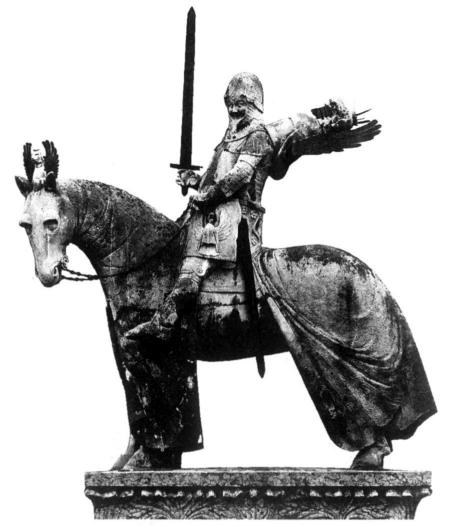

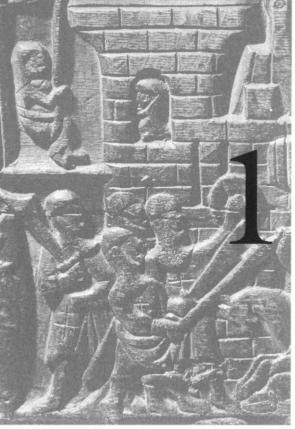

'ARFARE was a formative influence on the civilization and the social structures of the European middle ages. Its history in that period is in consequence of high significance alike for those who are interested in the middle ages for themselves and for their legacy, and for those whose interest is in war and its place in the story of human development. The twelve of us who have collaborated in the writing of this book have sought to bear both these parties in mind. We have also borne much in mind the richness of the material that can illustrate visually the importance of warfare to lives and minds in the medieval age: castles which still stand; artefacts and archaeological remains; tombs and monumental brasses depicting warriors in their armour; vignettes of battle and campaign in illuminated manuscripts. Our book has been conceived and planned not just as a history, but as an illustrated history.

'ARFARE was a formative influence on the civilization and the social structures of the European middle ages. Its history in that period is in consequence of high significance alike for those who are interested in the middle ages for themselves and for their legacy, and for those whose interest is in war and its place in the story of human development. The twelve of us who have collaborated in the writing of this book have sought to bear both these parties in mind. We have also borne much in mind the richness of the material that can illustrate visually the importance of warfare to lives and minds in the medieval age: castles which still stand; artefacts and archaeological remains; tombs and monumental brasses depicting warriors in their armour; vignettes of battle and campaign in illuminated manuscripts. Our book has been conceived and planned not just as a history, but as an illustrated history.

The book is divided into two parts, the first chronological, the second thematic. In the first part a series of chapters explores the impact of wars and fighting over time, from the Carolingian period down to the end of the Hundred Years War. There follow in the second part thematic discussions of specific aspects of warfare and its conduct: castles and sieges; war-horses and armour; mercenaries; war at sea; and the fortunes of the civilian in wartime.

In the process of putting the book together a great many obligations have been incurred, which must be gratefully acknowledged. We are all of us indebted to the successive editors at the Oxford University Press who watched over our work, Tony Morris, Anne Gelling, Anna Illingworth, and Dorothy McLean. We owe a major debt of gratitude to Sandra Assersohn, for her wise and patient help in the quest for apposite illustrations; and to Frank Pert who compiled the index. Each of us has besides debts of personal gratitude to friends and colleagues who read our contributions in draft and offered their advice and criticism. My own debt as editor is above all to my fellow contributors, who have worked together with such courtesy and despatch, from the book's conception to its completion. We all hope the results may prove worth the generosity of those who have done so much to help us.

MAURICE KEEN

ix

xi

Maurice Keen

1. PHASES OF MEDIEVAL WARFARE

Timothy Reuter

H. B. Clarke

John Gillingham

Peter Edbury

Norman Housley

Clifford J. Rogers

II. THE ARTS OF WARFARE

Richard L. C. Jones

Andrew Ayton

Michael Mallett

Felipe Fernandez-Armesto

Christopher Allmand

Maurice Keen

HE philosophical tradition of what we call the Western world had its origins in ancient Greece, its jurisprudential tradition in classical Rome. Christianity, the religion of the West, was nursed towards its future spiritual world status in the shelter of Roman imperial domination. Yet the political map of Europe, the heartland of Western civilization, bears little relation to that of the classical Hellenistic and Roman world. Its outlines were shaped not in classical times, but in the middle ages, largely in the course of warfare. That warfare, brutal, chaotic, and at times seemingly universal, is historically important not only for its significance in defining the boundaries and regions of the European future. Fighting in the medieval period, in the course of regional defence against incursions of non-Christian peoples with no background or connection with the former Roman world, and in the course of wars of expansion into territories occupied by other peoples, both Christian and non-Christian, and their absorption, played a vital role in the preservation for the future West of its cultural inheritance from antiquity. It also furthered the development of technologies that the antique world had never known.

HE philosophical tradition of what we call the Western world had its origins in ancient Greece, its jurisprudential tradition in classical Rome. Christianity, the religion of the West, was nursed towards its future spiritual world status in the shelter of Roman imperial domination. Yet the political map of Europe, the heartland of Western civilization, bears little relation to that of the classical Hellenistic and Roman world. Its outlines were shaped not in classical times, but in the middle ages, largely in the course of warfare. That warfare, brutal, chaotic, and at times seemingly universal, is historically important not only for its significance in defining the boundaries and regions of the European future. Fighting in the medieval period, in the course of regional defence against incursions of non-Christian peoples with no background or connection with the former Roman world, and in the course of wars of expansion into territories occupied by other peoples, both Christian and non-Christian, and their absorption, played a vital role in the preservation for the future West of its cultural inheritance from antiquity. It also furthered the development of technologies that the antique world had never known.

Because the notion of sovereign governments with an exclusive right to war-making was in the early middle ages effectively absent and only developed slowly during their course, medieval wars came in all shapes and sizes. To Honore Bouvet, writing on war in the later fourteenth century, the spectrum seemed so wide that he placed at the one extreme its cosmic level-'I ask in what place war was first found, and I disclose to you it was in Heaven, when our Lord God drove out the wicked angels'- and at the other the confrontation of two individuals in judicial duel by wager of battle. In between, he and his master John of Legnano placed a whole series of levels of human wars, graded according to the authority required to licence them and the circumstances which would render participation in them legitimate. For the historian, it is easy to think of alternative approaches to categorization to this that Bouvet offered to his contemporaries: indeed the problem is that there are almost too many possibilities to choose from.

'ARFARE was a formative influence on the civilization and the social structures of the European middle ages. Its history in that period is in consequence of high significance alike for those who are interested in the middle ages for themselves and for their legacy, and for those whose interest is in war and its place in the story of human development. The twelve of us who have collaborated in the writing of this book have sought to bear both these parties in mind. We have also borne much in mind the richness of the material that can illustrate visually the importance of warfare to lives and minds in the medieval age: castles which still stand; artefacts and archaeological remains; tombs and monumental brasses depicting warriors in their armour; vignettes of battle and campaign in illuminated manuscripts. Our book has been conceived and planned not just as a history, but as an illustrated history.

'ARFARE was a formative influence on the civilization and the social structures of the European middle ages. Its history in that period is in consequence of high significance alike for those who are interested in the middle ages for themselves and for their legacy, and for those whose interest is in war and its place in the story of human development. The twelve of us who have collaborated in the writing of this book have sought to bear both these parties in mind. We have also borne much in mind the richness of the material that can illustrate visually the importance of warfare to lives and minds in the medieval age: castles which still stand; artefacts and archaeological remains; tombs and monumental brasses depicting warriors in their armour; vignettes of battle and campaign in illuminated manuscripts. Our book has been conceived and planned not just as a history, but as an illustrated history.

HE philosophical tradition of what we call the Western world had its origins in ancient Greece, its jurisprudential tradition in classical Rome. Christianity, the religion of the West, was nursed towards its future spiritual world status in the shelter of Roman imperial domination. Yet the political map of Europe, the heartland of Western civilization, bears little relation to that of the classical Hellenistic and Roman world. Its outlines were shaped not in classical times, but in the middle ages, largely in the course of warfare. That warfare, brutal, chaotic, and at times seemingly universal, is historically important not only for its significance in defining the boundaries and regions of the European future. Fighting in the medieval period, in the course of regional defence against incursions of non-Christian peoples with no background or connection with the former Roman world, and in the course of wars of expansion into territories occupied by other peoples, both Christian and non-Christian, and their absorption, played a vital role in the preservation for the future West of its cultural inheritance from antiquity. It also furthered the development of technologies that the antique world had never known.

HE philosophical tradition of what we call the Western world had its origins in ancient Greece, its jurisprudential tradition in classical Rome. Christianity, the religion of the West, was nursed towards its future spiritual world status in the shelter of Roman imperial domination. Yet the political map of Europe, the heartland of Western civilization, bears little relation to that of the classical Hellenistic and Roman world. Its outlines were shaped not in classical times, but in the middle ages, largely in the course of warfare. That warfare, brutal, chaotic, and at times seemingly universal, is historically important not only for its significance in defining the boundaries and regions of the European future. Fighting in the medieval period, in the course of regional defence against incursions of non-Christian peoples with no background or connection with the former Roman world, and in the course of wars of expansion into territories occupied by other peoples, both Christian and non-Christian, and their absorption, played a vital role in the preservation for the future West of its cultural inheritance from antiquity. It also furthered the development of technologies that the antique world had never known.