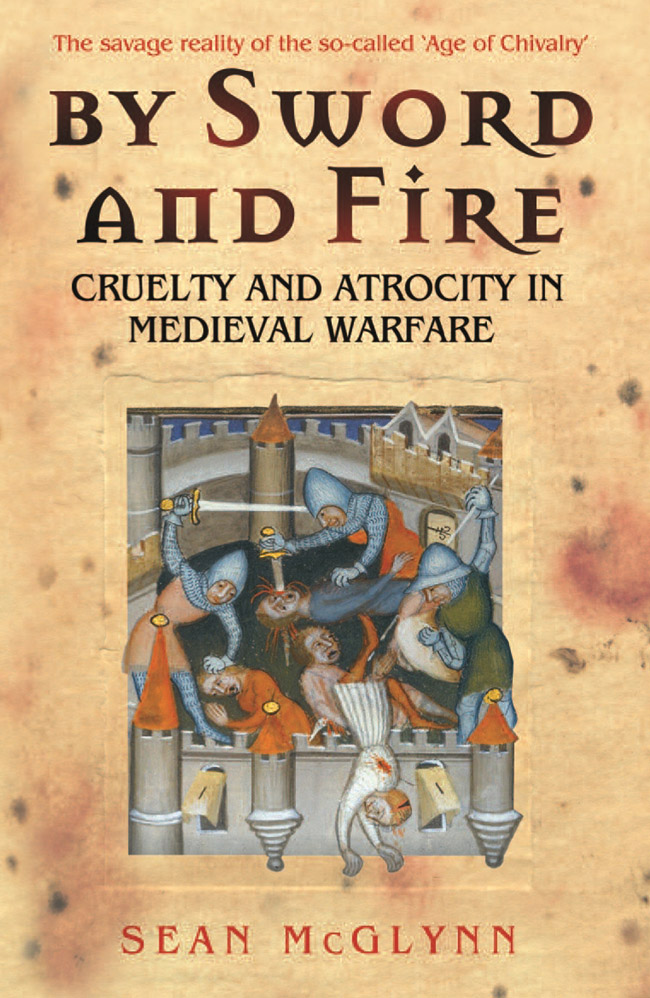

Sean McGlynn is Lecturer in Lifelong Learning, School of Humanities, University of Bristol and the author of Blood Cries Afar: The Forgotten Invasion of England 2016. He has contributed to a number of books, including the Cassell Atlas of the Medieval World, Readers Guide to Military History and Oxford University Presss Encyclopaedia of Medieval Welfare. He is a regular contributor to many journals and magazines, including History Today, English Historical Review, History, French History, Canadian Journal of History and The Times Higher Education Supplement. He lives near Bath.

BY SWORD

AND FIRE

Cruelty and Atrocity in

Medieval Warfare

Sean McGlynn

PHOENIX

But unfortunately the truth about atrocities is far worse than that they are lied about and made into propaganda. The truth is that they happen. The fact often adduced as a reason for scepticism that the same horror stories come up in war after war merely makes it rather more likely that these stories are true. Evidently they are widespread fantasies, and war provides an opportunity of putting them into practice These things really happened, that is the thing to keep ones eye on.

GEORGE ORWELL, Looking Back on the Spanish War

For my mother and

in memory of my father

CONTENTS

Jerusalem, 1099

When the Armistice was declared at the end of the First World War, a conflict that had left over eight million dead, the poet Sir Henry Newbolt rather crassly exhorted his readers: Think of chivalry victorious. The myth of chivalry has proven persistent. The allure of Chaucers verray, parfit gentil knyght remains irresistible for its image of a powerful warrior devoted to the ideals of bravery, honour, loyalty and self-sacrifice, all in the service not just of his lord or lady, but also for his role as protector of the weak, the elderly, the young and the defenceless. That Chaucer could describe his knight in such terms appears initially to military historians as a contradiction in terms: a gentle knight was not much use on the battlefield. Chaucer was writing in the second half of the fourteenth century, at a time when the ravages of the Hundred Years War and violent peasant uprisings had racked England and France with breathtaking brutality, as we shall see. Chaucer, with his high connections and travels across Europe, was well aware of these brutalities. His parfait, gentil knyght was a call to an idealized version of knighthood, prompted by the horrors of endemic warfare and social unrest.

Chaucer was following in the tradition of a long line of medieval writers who sought to mitigate the excesses of war in the Middle Ages through an appeal to the nobler instincts of knights. This literary genre is the subject of Richard W. Kaeupers book, Chivalry and Violence in Medieval Europe (1999), in which the author explores medieval writers attempts at reform in calling for a return to the true values of chivalry. However, at the same time, other writers were calmly accepting or, indeed, were encouraging the waging of war against non-combatants as the most practical way to achieve victory, even going so far as to justify these measures as being in accordance with chivalric values. The pragmatists retained their ascendancy over the idealists. This book examines what this meant for non-combatants in the wars of the Middle Ages and explains the rationale the military imperative that lay behind the atrocities committed.

I began studying medieval warfare in London just over twenty years ago, at a time when the revisionist school of medieval military historians there was making its important researches known. There are few who now believe that warfare in the Middle Ages was an amateurish and haphazard affair. However, the military atrocities of the age are still too frequently regarded as the natural outbursts of a violent age. The limitations of chivalry and the reality of medieval warfare have been the subject of exceptional scholarship by such medievalists as John Gillingham, Matthew Strickland and Christopher Allmand. This scholarship is deservedly acknowledged in academic circles, and at times I have drawn heavily on their work in their own particular fields. But the very nature of such research has perforce meant that it has been tightly focused in terms of period and region and that its audience has predominantly been a narrow, academic one. (Matthew Stricklands outstanding War and Chivalry: The Conduct and Perception of War in England and Normandy, 10661217 (Cambridge University Press, 1996) is especially worthy of note here, not least because the research originally in the shape of a PhD thesis has taken the form of a book, albeit one designed for an academic readership.)

In this book I attempt to present the findings of recent research, including my own, in an accessible way to a broader readership that will demonstrate clearly that medieval atrocities were not simply the result of ill-disciplined soldiers sating their blood lust, or the abhorrent acts of aberrant knights acting out of character. I explain these atrocities in detail within their immediate and more general military context. In its geographical and chronological scope ranging across the whole Middle Ages and the Latin world to encompass the crusading movement in the Middle East I believe that this is the first book of its kind on this important subject.

The savagery of medieval warfare is widely acknowledged and understood; yet the idea of chivalry as an important and influential force in the conflicts of the Middle Ages somehow lives on in seemingly comfortable juxtaposition with this awareness. In By Sword and Fire I show that such notions of incongruent compatibility do not reflect the reality of the times. As far as the practicalities of war are concerned, chivalry has been showered with too much attention. It represented but one small facet of medieval warfare; for non-combatants, it was so small a part of warfare as to be inconsequential. Although, as Malcolm Vale has shown in his important study War and Chivalry: Warfare and Aristocratic Culture in England, France and Burgundy at the End of the Middle Ages (1981), chivalry remained (with notable exceptions, I would argue) practical and flexible for the nobility at war throughout the medieval period, for non-combatants it remained, as I hope to show, pretty much as irrelevant as it had always been. Chivalry was a cult and a code for a small elite; it was not designed for the masses in warfare, be they ordinary soldiers or non-combatants.

This book, then, concerns itself not with chivalry but with warfare, with the realities of conflict and what it meant for non-belligerents. The chapters on atrocities are introduced with a brief explanation of how the central operations of warfare battles, sieges and campaigns were conducted and the role they played within overall strategy. In this way, the background to the atrocity can be understood in the light of the overriding military imperative.

No less importantly, I wish to emphasize that the atrocities described by medieval chroniclers were not merely the excitable outpourings of monkish hyperbole submerged in biblical and religious symbolism; rather, for all the undoubted exaggerations of many of these accounts, they reflect the reality and brutality of medieval warfare as the great figures of chivalry pursued their military objectives by whatever bloody means they deemed necessary.

When I had just finished writing this book, I began reading George Orwells essays. In his reflections on the Spanish Civil War of the 1930s, he comments on atrocity stories with his usual lucidity and perspicacity. These comments are reprinted at the beginning of this book; they summarize perfectly its conclusions.