Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

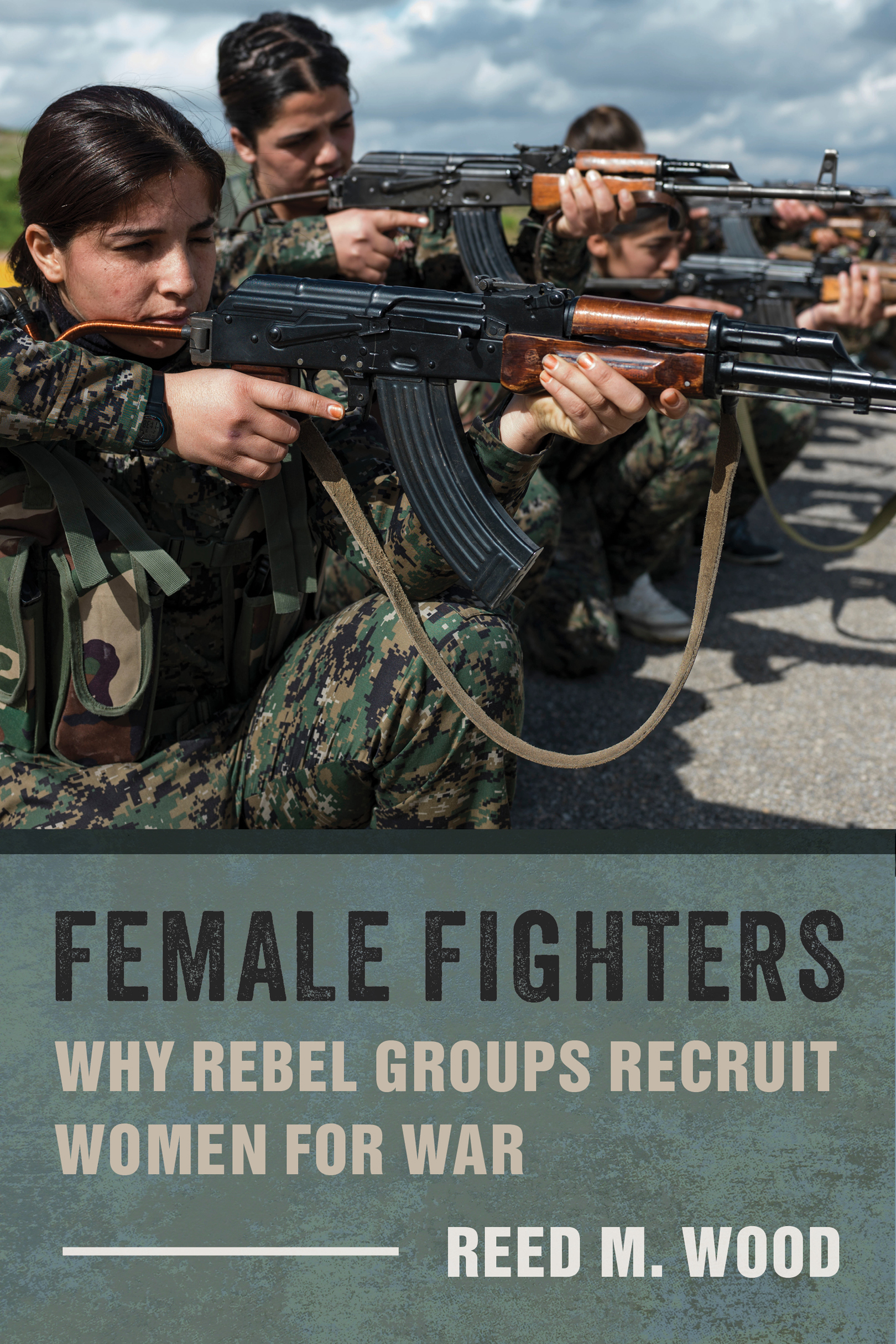

FEMALE FIGHTERS

FEMALE FIGHTERS

WHY REBEL GROUPS RECRUIT WOMEN FOR WAR

Reed M. Wood

Columbia University Press

New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2019 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-55009-3

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Wood, Reed (Reed M.), author.

Title: Female fighters : why rebel groups recruit women for war / Reed M. Wood.

Description: New York : Columbia University Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018060442| ISBN 9780231192989 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780231192996 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Women and war. | Women revolutionaries. | Insurgency. | WomenPolitical activity.

Classification: LCC U21.75 .W67 2019 | DDC 355.2/3082dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018060442

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: Lisa Hamm

Cover image: Newsha Tavakolian / Magnum Photos

Contents

Figures

Tables

A s implied by the title, this book focuses on female fighters and the mobilization of women in war. The intention of this book is not to glorify female combatants or treat them as a novelty. Rather, it is intended to acknowledge the important contributions that many thousands of women have made to contemporary rebellions in every region of the globe, to better understand the conditions that facilitate or discourage womens participation in organized political violence, and to begin thinking about the possible ways in which the presence of female combatants might influence the groups and rebellions in which they participate.

The theoretical orientation of this book is toward the motivations and strategic calculi of rebel groups and their leaders with respect to the choice of incorporating women in the groups combat forces or constraining and possibly eschewing their participation. Despite this focus on elite decision-making, I remain deeply interested in questions related to the motivations of individual women who elect to take up arms, how they navigate the social and institutional barriers that often impede or limit their participation in organized political violence, and their experiences within the (typically) overtly masculine organizations for whom they fight. Unfortunately, I am unable to address all of these questions in a single book; on the other hand, suspending consideration of the decisions made by the rank and file in order to more explicitly focus on group-level strategy formation allows me to develop a more focused, tractable set of arguments that help explain the variation in the prevalence of female combatants across armed groups and to begin exploring the strategic implications of their presence.

This book represents the culmination of a captivating intellectual journey. It reflects the intersection of numerous interests and fortuitous events. It is also the product of the invaluable input, insights, and collaboration of many different people. I officially began the project that ultimately led to the publication of this book in the summer of 2011, when I received as small seed grant to begin collecting data on female fighters. However, I trace the origins of the ideas and questions that formed the basis of this book to two unrelated trips to Central America years earlier. The first of these was a cultural education program in El Salvador I participated in during the summer of 2004. The organization that conducted the program was ideologically aligned with El Salvadors FMLN party, the party of the leftist rebels that had fought a twelve-year-long guerrilla war against the U.S.-backed government until reaching a negotiated settlement to the conflict in 1992. Among the most memorable aspects of this experience was the emphasis that the program placed on the roles Salvadoran women played in the rebellion and the number of female former FMLN guerrillas that worked with the program as guides, teachers, or volunteers. The second was a trip to El Salvador and Nicaragua to conduct predissertation fieldwork in the summer of 2008. While I was familiar with womens roles in the Salvadoran rebellion, prior to this trip, I was largely unaware of the substantial numbers of female fighters that had participated in both the Sandinista and Contra rebellions in neighboring Nicaragua. However, the handful of interviews I conducted with veterans groups in Managua, Esteli, and Somoto included a small number of former female guerrillas, and interviews with both men and women routinely referencedat least in passingwomens roles in the armed struggles. Because the focus of my dissertation lay elsewhere, I treated these encounters simply as interesting anecdotes but largely irrelevant to the project at hand.

Only a few years later, while participating in a faculty working group at Arizona State University that focused on gender and human rights, did I reflect on these experiences and start to think seriously about patterns of womens participation in armed conflict. I am therefore grateful to the coordinators of this working group, Linell Cady, Carolyn Forbes, and Carolyn Warner, for inviting me to participate and for providing the small grant that officially launched the project that has evolved (over many years) into this book. I am also indebted to Patrick Kenney and the ASU Institute for Social Science Research for providing me additional funding that allowed me to begin the data collection for the project in earnest in 2012 as well as the School of Politics and Global Studies, which has provided additional resources since then. The Kroc Institute of International Peace Studies at the University of Notre Dame graciously provided me invaluable space, time, and resources to conduct research for this book during the fall of 2014.

Numerous graduate and undergraduate students have assisted in the data collection for this project over many years, and each deserves thanks. I would like to acknowledge the many hours of research conducted by ASU students Lindsey Allemang, Aaron Ardley, Carissa Cunningham, Jamie Dorer, Bryan Eddy, Cassandra Long, Rachel Olsen, Daniel Pout, Rahul Prasai, Justin Tran, Holly Williamson, and Oona Zachary. I also thank Michigan State University students Daniel Hansen and Zuhaib Mahmood. I am particularly indebted to Jacquelyn Schneider, who has contributed as much as anyone to collecting the information on womens participation in armed groups that served as the basis of the Women and Armed Rebellion Dataset (WARD), the dataset of female combatant participation used throughout this book.

This book is, at core, the product of many collaborative works, and two of my colleagues and co-authors deserve particular thanks and credit for their contributions. The first is Jakana Thomas, the co-creator of WARD. This dataset represents the intersection of independent data collection efforts that we had unknowingly undertaken simultaneously. The African rebellion cases included in WARD are largely based on previous data collection and coding efforts that she and Kanisha Bond undertook for their path-breaking study of women in armed groups, which was published in the American Political Science Review . Our previously published co-authored work on this topic was also highly influential in the development of this book. Particularly, . The experiment discussed therein reflects a small part of a larger collaborative project on the topic of gender framing and audience attitudes toward foreign rebel groups. I thank her for allowing me to use a portion of that research in this book. Without either of their contributions this project would not have been possible.