Pagebreaks of the print version

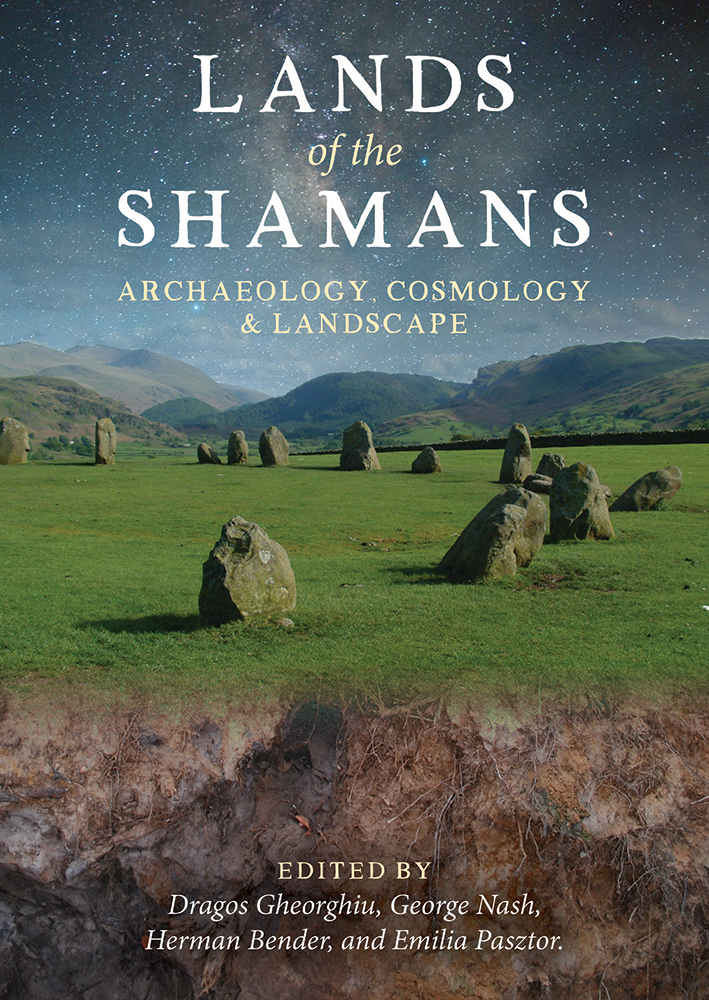

Lands of the Shamans

Archaeology, Cosmology and Landscape

Edited by

Drago Gheorghiu, George Nash, Herman Bender and Emlia Psztor

Published in the United Kingdom in 2018 by

OXBOW BOOKS

The Old Music Hall, 106108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JE

and in the United States by

OXBOW BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Road, Havertown, PA 19083

Oxbow Books and the individual contributors 2018

Paperback Edition: ISBN 978-1-78570-954-8

Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-78570-955-5 (epub)

Kindle Edition: ISBN 978-1-78570-956-2 (mobi)

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018951275

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the publisher in writing.

For a complete list of Oxbow titles, please contact:

UNITED KINGDOM | UNITED STATES OF AMERICA |

Oxbow Books | Oxbow Books |

Telephone (01865) 241249, Fax (01865) 794449 | Telephone (800) 791-9354, Fax (610) 853-9146 |

Email: | Email: |

www.oxbowbooks.com | www.casemateacademic.com/oxbow |

Oxbow Books is part of the Casemate Group

Back cover image: The deer panel, located on the elbow of the Ocreza River. (Photo by D. Gheorghiu)

Contributors

H ERMAN B ENDER

Hanwakan Center for Archeoastronomy, Cosmology and Cultural Landscape Studies, Inc. USA

A PELA C OLORADO

Worldwide Indigenous Science Network, USA

E NRICO C OMBA

Universit degli Studi di Torino, Dipartimento di Culture, Politica e Societ, Turin, Italy

P AUL D EVEREUX

(i)Royal College of Art; (ii)Time & Mind journal, UK

E KATERINA D EVLET

Institute of Archaeology Russian Academy of Sciences, Centre of Paleoart Studies, Moscow, Russia

S ARA G ARCS

Trs-os-Montes e Alto Douro University, UTAD, Quinta de Prados, 5000-801 Vila Real, Portugal; Earth and Memory Institute (ITM), Quaternary and Prehistory Group of the Geosciences Centre (u. ID73 FCT). FCT Scholarship (SFRH/ BD/69625/2010), Portugal

D RAGO G HEORGHIU

Doctoral School, National University of Arts, Bucharest, Romania;

Earth and Memory Institute (ITM), Quaternary and Prehistory Group of the Geosciences Centre (u. ID73 FCT), Portugal

R YAN H URD

Worldwide Indigenous Science Network, USA

C AROLINE M ALIM

SLR Consulting Limited, Hermes House, Oxon Business Park, Shrewsbury, UK

G EORGE N ASH

Department of Archaeology and Anthropology of University of Bristol, UK

E MLIA P SZTOR

Trr Istvn Museum, Baja, Hungary

V LADIMR P EA

Regional Museum and Gallery at esk Lpa, Czech Republic

C HRIS S CARRE

Department of Archaeology, Durham University, UK

M ICHEL L OUIS S FRIADS

Anthropologue et archologue honoraire au Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), Paris, France

Introduction: Towards a Landscape for Shamans

The Editors

Setting the Scene

Over the past 20 years, shamanism has become an emerging topic in archaeology see Price (2001); David Lewis-Williams (2002), Guba & Szevereny (2007), Mannermaa (2008), Psztor (2011), Reymann (2015), Gheorghiu et al . (2017), Rozwadowski (2017). It has begun to emerge that shamanism can take on many guises; from the potential shamanism of the very ancient world of our Palaeolithic ancestors to the Neoshamanic practices of the Counterculture of the late 20th century (Lewis-Williams 2002; Nash 2017). The various strands recognised within this subject clearly shows that shamanism, like other subjects, relies on many mechanisms in order to survive and flourish; one of these is landscape. As far as we the authors are concerned, this edited volume is the first of its kind to associate shamanism with landscape as clearly, the two interact.

If we accept shamanism (or a belief-system best described with a shamanistic world view, see Winkelman 2004) was already a generic phenomenon in the prehistoric times, then we should be able to use shamanism as an ethnographic analogy in order to analyse certain archaeological artefacts. Reconstructing a belief-system with the help of archaeological artefacts is often difficult and rarely straightforward (see Gheorghiu et al. 2017). However, we cannot overlook the possibility of shamanism being used, regardless the sceptics, as a possible analogy during the research of prehistoric beliefs.

The most characteristic element of shamanic ritual is the way special individuals would enter into an altered state of consciousness (ASC). There can be many explanations behind this, even physiological, as confirmed through anthropological research. Thanks to this even one of the richest graves from the Mesolithic period, discovered in 1930 in Bad Drrenberg, Germany was considered to belong to a shaman. Anatomical changes to the female skull intimated frequent shifts into transient state.

Based on fragmentary archaeological evidence and documentary ethnographic accounts, shamans often used hallucinogen substances to reach altered states of consciousness. Trace elements of opium poppy have been found among archaeological artefacts on the eastern and southern slopes of the Jura Mountain from almost every period (Merlin 2003); here, the landscape plays a significant role in the shamanistic beliefs.

Many scientists trace back the origin of shamanism to later prehistory. However, as far back as the 1950s, Russian scientists have claimed that Siberian shamanism, in fact, originates from a much earlier period and can be regarded as an ideological background for the analysis of rock art (Okladnikov & Martinov 1972); sentiments that were later supported by Lewis-Williams and Dowson (1988, 1990), Clottes and Lewis-Williams (1998) and Whitley (1998). The eminent Russian prehistoric historian Okladnikov considered the origin of shamanism to date to the Neolithic, around 30004000 BCE (Okladnyikov 1972). Bronze Age craftsmanship among the Western-Siberian Obi-Ugrians, dating between the 8th century BCE and 17th century CE, supports the concept of belief-systems being influenced by ASC. Many archaeologists working within this geographical area regard the figurines found at the Achmylovo site (on the Upper-Volga and dating back to between 8th and 6th century BCE) as devices used in shamanistic practices (Schwerin von Krosigk 1992). They believe that recovered artefacts such as amulets, jewellery and other items of dwelling adornment would have assisted in warding away evil spirits within the house; a practice that is recorded within both the anthropological and ethnographic records (Fedorova 2001; Patrushev 2000). Interestingly, the geographical range of these amulets is replicated in the present day, suggesting that the ancient practices are still in use.

If the term shaman represents a special perception of the world, then shamans are creators of interaction between this world and the other world through the ecstatic role-taking technique (Siikala 1978, 2830). This definition suggests that we are not witnessing a world of chaos rather more a world of order whereby the shaman would have had control of the community; but at the same time, would have been the direct device between the community and spirit world. The spirit world would have been comprised of things us mortals cannot and should not see. In prehistoric times until relatively recent times, sections of landscape would have been ritualised and strictly taboo. This is witnessed in the way prehistoric ritualised monuments, burial or landscape markers are concentrated in clusters and are located away from settlements. The organisation of space sacred and profane occurs in all areas of the world and one considered the segregation of these spaces as being a fundamental human trait that evokes social and political control in hierarchies (e.g. using landscape to segregate class and gender).