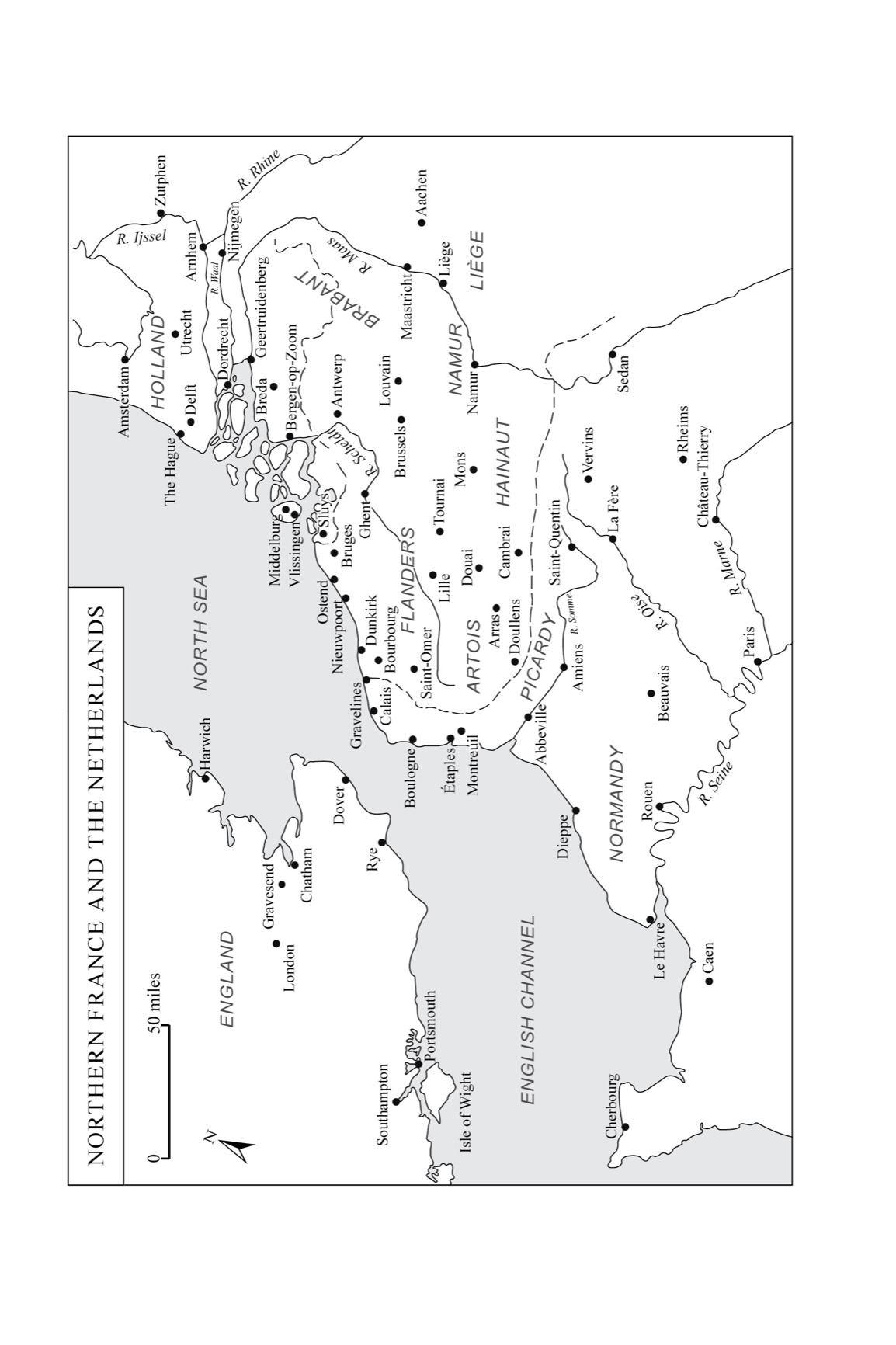

Dates are given throughout this book in the Old Style Julian Calendar in use in England during the sixteenth century, but the year is assumed to have begun on 1 January, not on Lady Day, or the Feast of the Annunciation (25 March), which then by custom was the first day of the calendar year. The New Style Gregorian Calendar, advancing the date by ten days, was issued in Rome in 1582 and adopted in Italy and by Philip II throughout Spain, Portugal and the New World in October that year. France followed in December, as did Brabant, Flanders, Holland and Zeeland in the Netherlands. The Catholic states of the Holy Roman Empire followed in 1583. England, Scotland, Ireland, Denmark and Sweden retained the old calendar until the 1700s, as did Friesland, Gelderland and Overijssel in the Netherlands. For obvious reasons of consistency, dates given in primary sources using the new Gregorian Calendar are converted to match the Julian Calendar used elsewhere.

Spelling and orthography of primary sources in quotations are for the most part given in modernized form. Modern punctuation and capitalization have also been provided where none exists in the original manuscript.

Units of currency appear in the pre-decimal form in use until 1971. There are twelve pence (12d.) in a shilling (modern 5 pence or US 8 cents), twenty shillings (20s.) in a pound (1 or US $1.60), and so on. Modern purchasing equivalents for sixteenth-century figures are extremely difficult to calculate, as the effects of inflation and huge fluctuations in the relative values of land and commodities render them misleading, but rough estimates may be obtained by multiplying all numbers by a thousand.

Preface

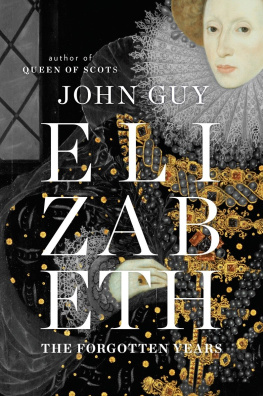

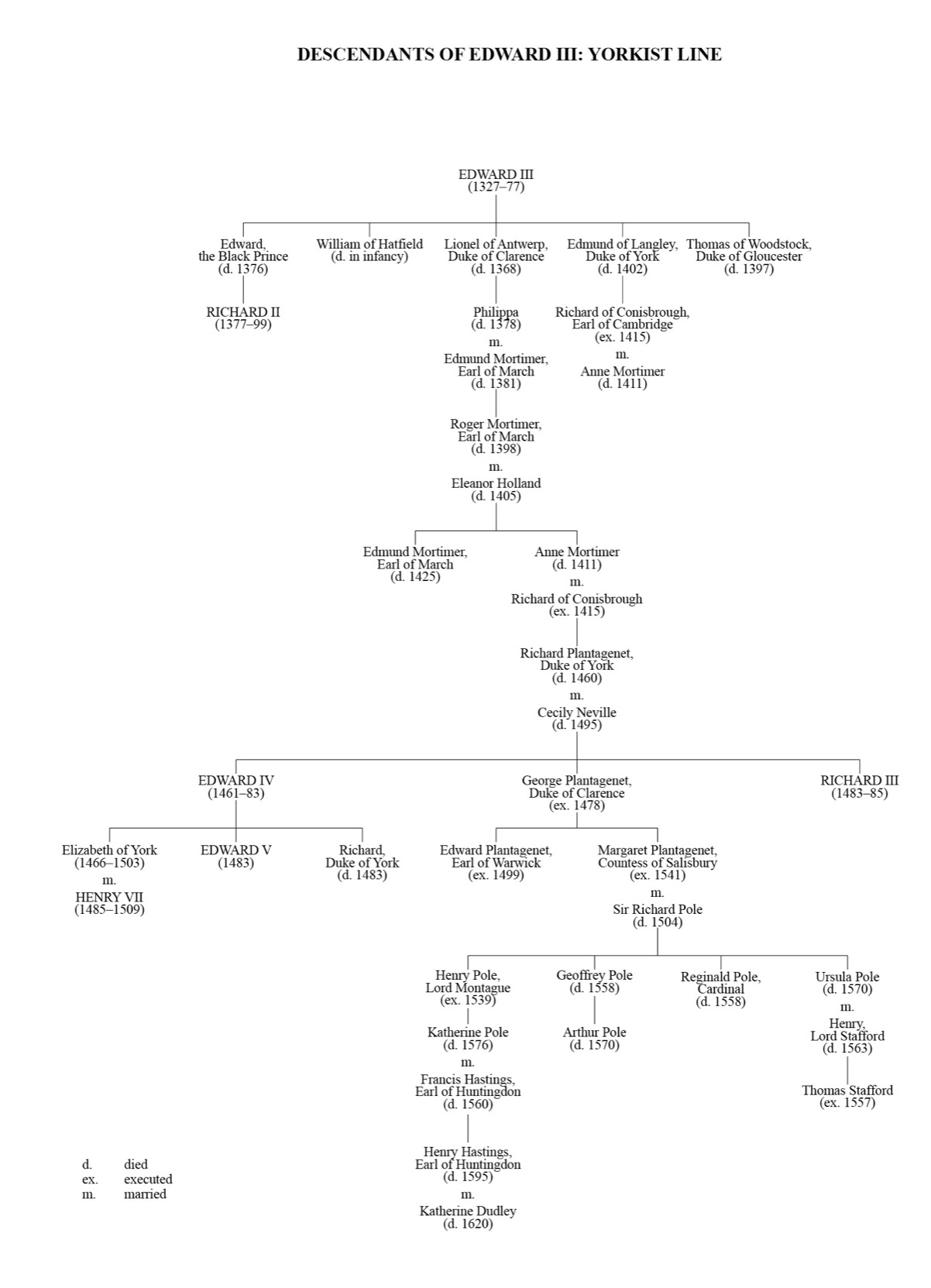

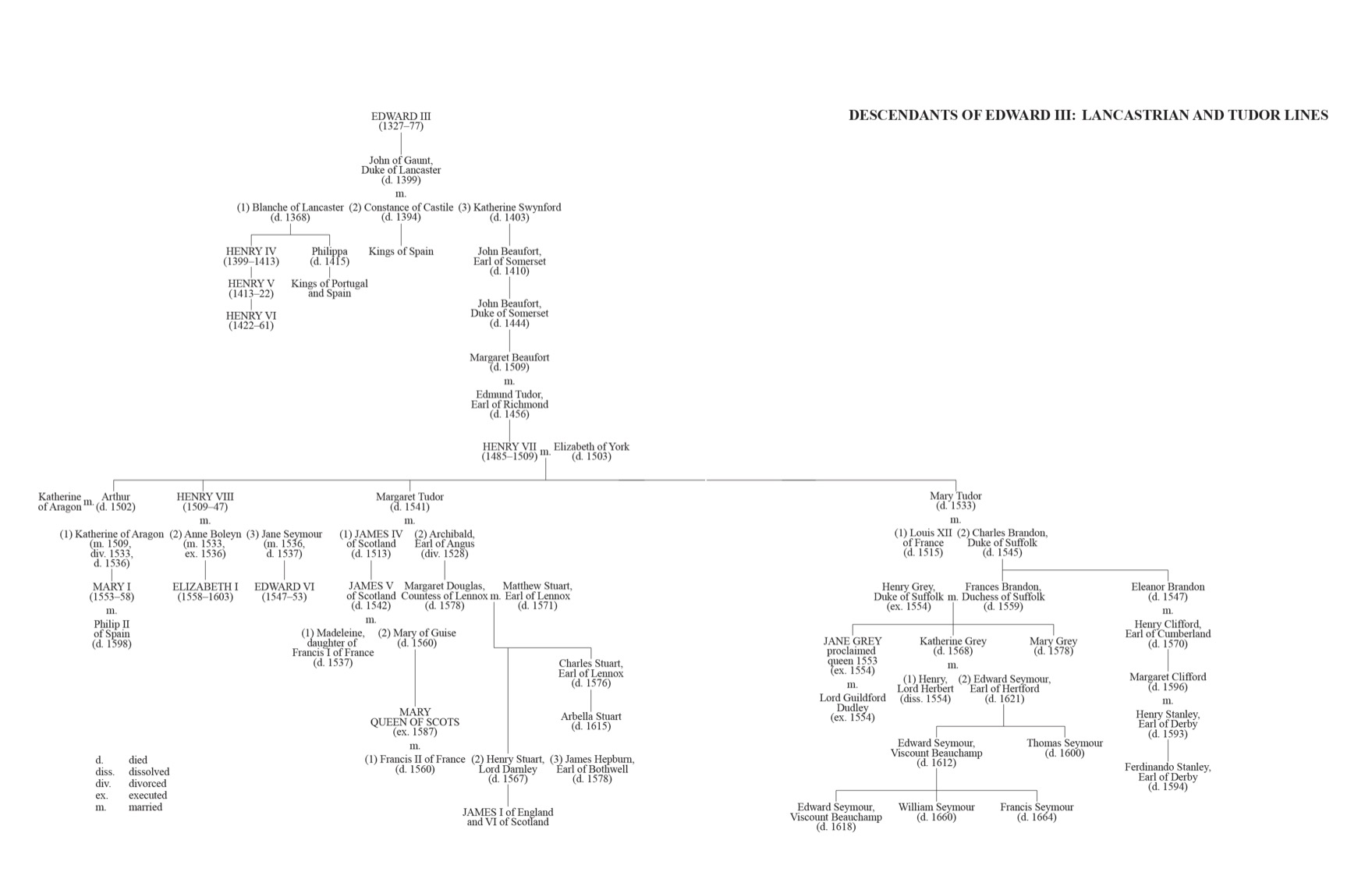

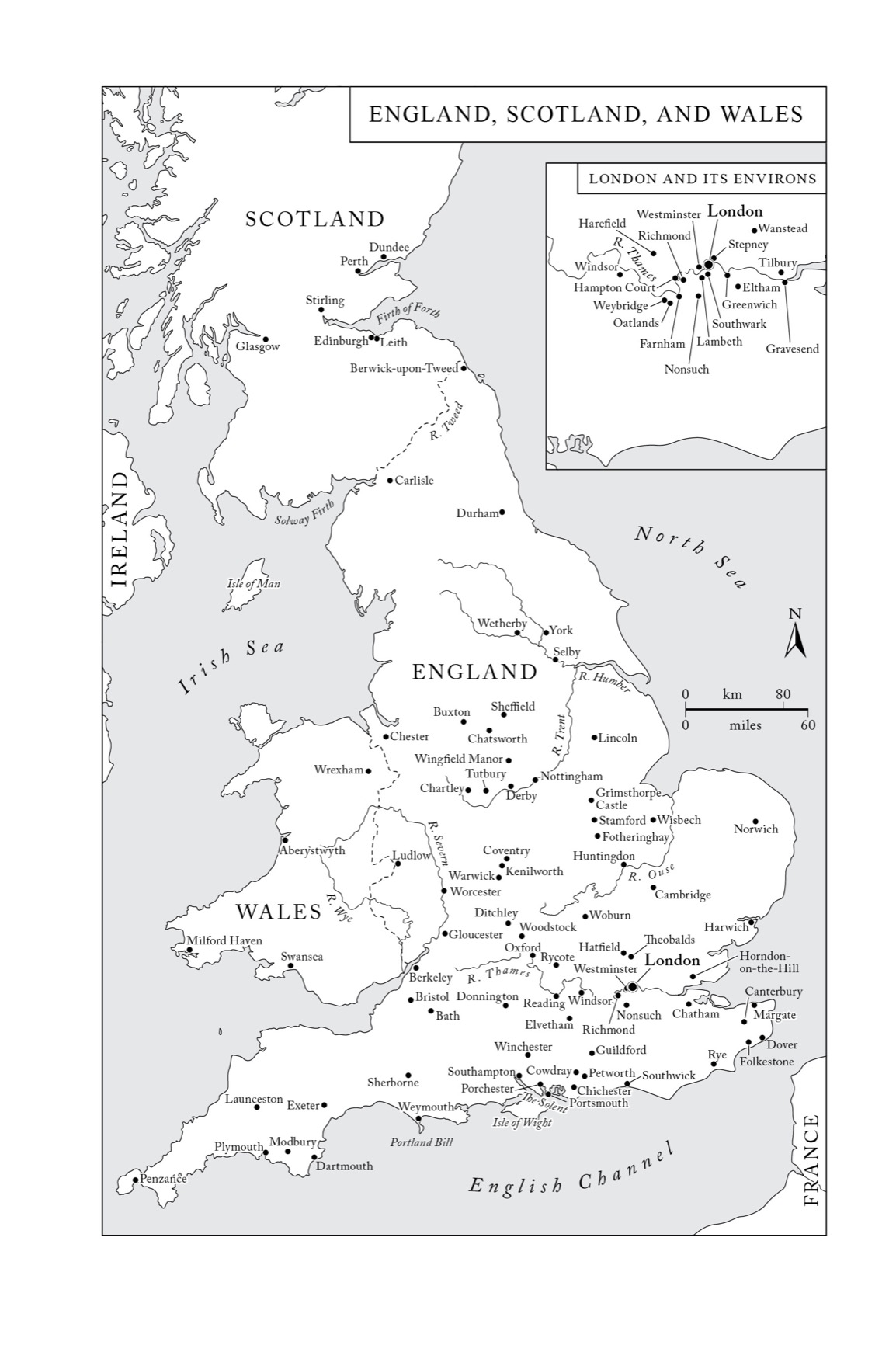

Elizabeth was born at Greenwich Palace shortly after three oclock on the afternoon of Sunday, 7 September 1533. The granddaughter of Henry VII, the Tudor dynastys founder, and daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, she was the last of her fathers children to inherit the throne. After a run of chastening, sometimes terrifying experiences during her Catholic half-sister Mary Tudors reign, she was proclaimed queen by the heralds on the early morning of Thursday, 17 November 1558. Anointed and crowned in Westminster Abbey at the age of twenty-five, she ruled for forty-four years, longer than any of her adult predecessors apart from Edward III, a considerable achievement in itself.

With so many years to cover, Elizabeths biographers have tended to flag once she passed the age of fifty. Having established a pattern for the years of peace before the arrival of the Spanish Armada of 1588, they either skate over the years dominated by war or fall back on the convenient short cut of William Camdens monumental Annales (he wrote in Latin), completed in 1617 and published in two unequal instalments between 1615 and 1627. The book, now better known as The History of Elizabeth , is a mini-archive in itself. But it is a treacherous guide.

Despite Camdens claim to have written an unbiased history firmly rooted in the archives, a forensic comparison of his quotations with the original documents shows that he regularly doctored his sources to fit his theories. His account institutionalized a whole raft of hoary myths full of reverential nostalgia for the dead queen. To insulate her from criticism, he drew a veil over her vanity and her temper tantrums. Most conspicuously, he glided over topics that were still politically explosive when he was writing. Usually, this meant anything connected to the question of the succession and particularly to Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots, whom, sensationally, Elizabeth had executed. Anxious not to offend the new king of England, Marys watchfully indolent son James I, whose re-interment of his mother in a spectacular marble tomb at Westminster Abbey was taking place even as the earliest draft of the Annales was approaching completion, Camden was also eager to protect the reputation of his former patron, Sir William Cecil, who had served Elizabeth faithfully (if in his own way) from the time she was barely sixteen.

Worse still, Camdens bestselling translator, the gunner and mathematician Robert Norton, barely an adult when Elizabeth died, cheerfully proceeded to bowdlerize the Annales while preparing the English version most commonly available today. Between 1630 and 1635, years during which Charles Is suitability to rule first began to be seriously challenged by critics of the monarchy, Norton inserted many spurious interpolations into his three English editions of Camdens text. With the barely cloaked intention of using Elizabeth as a stick with which to beat her Stuart successors, Norton spun fresh legends, chiefly concerning the (allegedly) spontaneous outpourings of love and devotion to Good Queen Bess: he has her devoted subjects running, flying, flocking to be blessed by the sight of her glorious countenance as oft as ever she came forth in public.

Deeply versed in such apocryphal material, the biographers writing after the accession of Queen Victoria in 1837 raised Elizabeth to dizzy heights of veneration. After personally nursing her divided people through a Protestant Religious Settlement in 1559 that commanded wide assent (or so these authors believed), the fiery, red-haired heroine who shaped Englands destiny went on to stride boldly where her advisers feared to tread. A cultural icon who presided over the greatest flowering of literature and art that the country had ever seen, she was the woman who had chosen to live her life as a Virgin Queen, marrying her realm (as her propagandists liked to say) and so dedicating herself to the welfare of the people she loved so dearly, despite the personal cost.