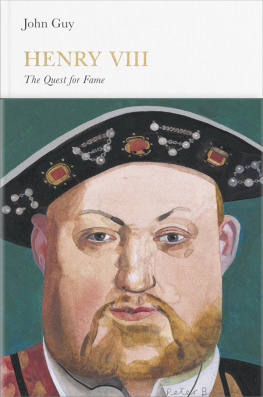

John Guy

HENRY VIII

The Quest for Fame

Contents

Penguin Monarchs

THE HOUSES OF WESSEX AND DENMARK

| Athelstan | Tom Holland |

| Aethelred the Unready | Richard Abels |

| Cnut | Ryan Lavelle |

| Edward the Confessor | James Campbell |

THE HOUSES OF NORMANDY, BLOIS AND ANJOU

| William I | Marc Morris |

| William II | John Gillingham |

| Henry I | Edmund King |

| Stephen | Carl Watkins |

| Henry II | Richard Barber |

| Richard I | Thomas Asbridge |

| John | Nicholas Vincent |

THE HOUSE OF PLANTAGENET

| Henry III | Stephen Church |

| Edward I | Andy King |

| Edward II | Christopher Given-Wilson |

| Edward III | Jonathan Sumption |

| Richard II | Laura Ashe |

THE HOUSES OF LANCASTER AND YORK

| Henry IV | Catherine Nall |

| Henry V | Anne Curry |

| Henry VI | James Ross |

| Edward IV | A. J. Pollard |

| Edward V | Thomas Penn |

| Richard III | Rosemary Horrox |

THE HOUSE OF TUDOR

| Henry VII | Sean Cunningham |

| Henry VIII | John Guy |

| Edward VI | Stephen Alford |

| Mary I | John Edwards |

| Elizabeth I | Helen Castor |

THE HOUSE OF STUART

| James I | Thomas Cogswell |

| Charles I | Mark Kishlansky |

| [Cromwell | David Horspool] |

| Charles II | Clare Jackson |

| James II | David Womersley |

| William III & Mary II | Jonathan Keates |

| Anne | Richard Hewlings |

THE HOUSE OF HANOVER

| George I | Tim Blanning |

| George II | Norman Davies |

| George III | Amanda Foreman |

| George IV | Stella Tillyard |

| William IV | Roger Knight |

| Victoria | Jane Ridley |

THE HOUSES OF SAXE-COBURG & GOTHA AND WINDSOR

| Edward VII | Richard Davenport-Hines |

| George V | David Cannadine |

| Edward VIII | Piers Brendon |

| George VI | Philip Ziegler |

| Elizabeth II | Douglas Hurd |

Authors Note

Dates are given in the Old Style Julian calendar, but the year is assumed to have begun on 1 January, and not on Lady Day, the feast of the Annunciation (i.e. 25 March), which was by custom the first day of the calendar year in France, Spain and Italy until 1582, in Scotland until 1600, and in England, Wales and Ireland until 1752.

Spelling and orthography of primary sources in quotations are given in modernized form. Modern punctuation and capitalization are provided where there is none in the original manuscript.

Money appears in the pre-decimal form in use until 1971. There are twelve pence in a shilling (modern 5p or US 8 cents), twenty shillings in a pound (1 or US$ 1.60), and so on. Modern equivalents for sixteenth-century figures are extremely difficult to calculate, as the effects of inflation and huge fluctuations in the relative values of land and commodities render modern equivalents misleading, but rough estimates may be obtained by multiplying all the numbers by a thousand.

Introduction

Few monarchs have divided opinion more than Henry VIII. Inevitably so, because besides doing more than any other English king to reshape the countrys institutions and identity in roughly the form they survive today, he was also a wilful destroyer. For those who opposed his attacks on the Church and hefty demands of taxation, he was a vindictive tyrant who associated might with right and value with lustre. He was, said John Hale, a priest of Isleworth in Middlesex, to be called a great tyrant rather than a king. Allowed his day in court by Henry before being sent to the gallows on a charge of high treason, Hale was determined to put his views on the record. Since the realm of England was first a realm, he insisted, was there never in it so great a robber and pillager of the commonwealth read of nor heard of as is our king.

Others have strenuously disagreed. For perhaps a majority of his subjects, Henry was everything a king should be. Capable of the best as well as the worst, he exuded magnificence, both personally and through his spectacular palaces and art collections. His children revered and adored him. Faced with disobedience from her own privy councillors, his daughter Mary, who as the countrys first queen regnant sometimes found it an uphill struggle to establish her authority even with her closest supporters, declared that

Not surprisingly, criticisms of Henrys policies were linked to attacks on his private life. Comparing him to the infamous classical tyrant King Dionysius of Syracuse, Sir Thomas Elyot wrote:

He was a man of quick and subtle wit, but therewith he was wonderful sensual, unstable and wandering in sundry affections. Delighting sometime in voluptuous pleasures, another time in gathering of great treasure and riches, oftentimes resolved into a beastly rage and vengeable cruelty. About the public weal of his country always remiss, in his own desires studious and diligent.

But while Henry had six wives and several mistresses, he was, by the standards of his royal contemporaries, sexually restrained. And although two of his wives were executed and two divorced, it can be argued that dynastic security made such casualties necessary. Whereas those on the wrong side of Henry saw him as a tyrant ruled by his sexual passions, others (especially nobles and property owners keen to profit from the spoils of the annihilation of the abbeys) saw him as providing the essential stability that kept the country free of the civil wars that had plagued the fifteenth century or the wars of religion that would bring anarchy to France and the Netherlands later in the century.

Rather than attempt to vindicate the views of either side of the debate in this short reassessment, I will seek to look behind the mask into Henrys mind and explain how he himself understood events. How far did those of his childhood and adolescence make their indelible mark? What led him to shape his policies and choose his wives and ministers? Was he a ruler with genuine principles or deeply held convictions or simply an unscrupulous pragmatist? Was he devout and therefore sincere in demanding the massive changes and destruction wreaked upon the Church and the monasteries? What impelled him to attempt to become a commanding presence on the European stage, with all its immense costs, human and material? In particular, did his cruel streak come only latterly with age, disappointment and ill-health, or was it always there?

Keeping such questions to the fore will, I hope, open the door to unfamiliar as well as more familiar insights and enable readers to feel they can reach out and touch this charismatic and yet so difficult and complex king.