Henry and I go back a long way.

My first and second undergraduate essays at Cambridge, written in late 1964, were on his grandmother, Lady Margaret Beaufort, and his second wife, Anne Boleyn. My doctoral dissertation, begun in 1967 and finally completed in 1973, grew directly out of that second essay and was an in-depth study of his privy chamber and its staff. This was the department of the royal household that provided both the kings body service and his personal political aides. It was thus rather like the modern Downing Street or White House staff, and included individuals just as silky and shamelessly self-serving as their present-day equivalents.

One of them, William Compton, has a bit part in this book.

He was Henrys groom of the stool and I have only to write the words to be carried back almost four decades to the Cambridge University Library tea-room circa 1970. It is about 3.30 p.m. and I have met up with my fellow members of Geoffrey Eltons research seminar. We are a noisy, gregarious, grub-loving group. I am eating home-made lemon-cake with a gooey icing and filling and bits of grated lemon rind that occasionally get stuck between the teeth. I am also drinking lemon tea. And I am talking. And talking. About Henry and his groom of the stool.

Did you know the groom was act-ually I overemphasize the first syllable as though I were already on TV in charge of Henrys close-stool? What? Oh thats the royal loo. Yes. And that he certainly attended the king when he used it? How do you know, you say? Well, the groom says so. He even describes the contents solid as well as liquid. He may very well have wiped the royal bottom

No wonder my dissertation became known as doctoral faeces (say it fast!).

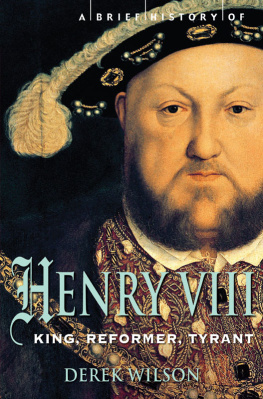

Happy days. And even they were not the beginning. Instead, another Cambridge scene, this time from my undergraduate days. I am sitting in one of Geoffrey Eltons lectures and nodding off. Suddenly, I jolt awake. Henry VIII, Elton announces, is the only king whose shape you remember. Then he turns to the blackboard behind him and draws a quick sketch. First, a trapezium for the body. Then two splayed lines for the legs. A pair of triangles form the arms. The head and neck are a single oblong, surmounted by an angled line for the hat.

Pause for laughter. Then, playing to the audience, Elton adds another, inverted triangle for the codpiece. More laughter and applause.

* * *

Elton was of course right. Holbeins portrait of Henry VIII, which he here reduced, brilliantly, to the bare essentials of its almost cubist geometry, is memorable. Almost too memorable indeed. For it not only eclipses other English monarchs, with the exception of Henrys daughter Elizabeth. It also obscures the other Henry.

The point is this: there are two Henrys, just as there are two Elizabeths, the one old, the other young. And they are very, very different. Especially in the case of Henry. Holbeins Henry is the king of his last dozen or so years, when he was in Charles Dickenss glorious phrase a spot of blood and grease on the history of England. This is the hulking tyrant, with a face like a Humpty Dumpty of nightmare, who broke with Rome and made himself supreme head of the church; who married six wives, of whom he divorced two and divorced and executed two others; who dissolved six hundred monasteries, demolished most of them and shattered the religious pieties and practices of a thousand years; who beheaded nobles and ministers, including those who had been his closest friends, castrated, disembowelled and quartered rebels and traitors, boiled poisoners and burned heretics.

This is also the king who reinvented England; presided over the remaking of English as a language and literature and began to turn the English Channel into the widest strip of water in the world. He carried the powers of the English monarchy to their peak. Yet he also left a damnosa hereditas to his successors which led, not very indirectly, to Charles Is execution one hundred and two years almost to the day after Henrys own death, and on a scaffold in front of the palace that Henry had made the supreme seat of royal government and where he himself had died.

But this is not the Henry of this book. This book is about the other Henry: the young, handsome prince, slim, athletic, musical and learned as no English ruler had been for centuries. This Henry loved his mother and most unusually for a boy at the time was brought up with his sisters, with all that implies about the civilizing and softening impact of female company. He was conventionally pious: he prostrated himself before images, went on pilgrimages and showed himself profoundly respectful of the pope as head of the church. He proclaimed that I loved true where I did marry, and meant it. He determined to knit up the wounds of the Wars of the Roses and restore the dispossessed. He abominated his fathers meanness, secrecy and corrosive mistrust. Instead he modelled himself on Henry V, the greatest and noblest of his predecessors. Or he would be a new Arthur with a court that put Camelot in the shade. At the least, he determined that his reign, which began when he was only seventeen years and ten months old, should be a fresh start.

And it was. Or at least it was believed to be. Lord Mountjoy, his socius studiorum (companion of studies), hailed his accession as the beginning of a new golden age. Thomas More, who had known Henry since the future king was eight years old, went further. Henry, he proclaimed in the verses he wrote to celebrate the coronation, was a new messiah and his reign a second coming.

Mountjoy we can perhaps discount. But More was nobodys fool. If he saw these extraordinary qualities in Henry then they, or something like them, must have been there indeed.

But there is a double difficulty. The first is of image. For there is no decent representation of the young Henry. There are a few panel portraits, but they are journeymens work and do not hold a candle to Holbeins blazing genius. And without an image it is difficult to turn the paeans of praise about the young Henry from a cold, idealized abstraction into a thing of warm flesh and blood.

Here I have tried to flesh out Henry through words including as much as possible of Henrys own words and those of his contemporaries. Often these were in Latin. Once this presented no difficulty. Now it is an obstacle, not only to the reader but to many scholars as well. For my own part, I pretend to little Classical scholarship. Instead I have freely resorted to translations, where they exist, and to the help of translators where they do not. The result has been enlightening and some of the most original material in the book has come from newly translated Latin sources. I am particularly grateful to Justine Taylor for her help in this regard.

* * *

The other problem is one of explanation and is more fundamental. For to talk of two Henrys is only a figure of speech. They were in fact the same person. Or at least they were the same man when old and young. But how to explain the spectacular change from one to the other?

Was the young Henry a sort of aberration? Was he really what he was to be in old age? Or was it all down to changing circumstances?

It can be put rather differently. Should we read him backwards, from what he became? Or forwards, from what he was?

Really there should be no question which. Modern scholarship is resolute that events must be read forward. It recognizes that the actors at the time were not gifted with foresight and it is clear that historians must not impose their own knowledge of what was to come on contemporaries who were necessarily ignorant of it. To do so is teleology. And to do so persistently is the ultimate sin of Whiggishness.