Copyright 2013 by Richard Rubin

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhbooks.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Rubin, Richard.

The last of the doughboys : the forgotten generation and their forgotten world war / Richard Rubin.

pages cm

Includes index.

ISBN 978-0-547-55443-3

1. World War, 19141918VeteransUnited States. 2. World War, 19141918 Personal narratives, American. 3. SoldiersUnited StatesBiography. 4. VeteransUnited StatesBiography. 5. CentenariansUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

D 639. V 48 U 67 2013

940.4'12730922dc23 2013000614

e ISBN 978-0-547-84369-8

v1.0513

Excerpts from Company K by William March (University of Alabama Press) used by permission of Harold Ober Associates Incorporated.

To them and those they represent

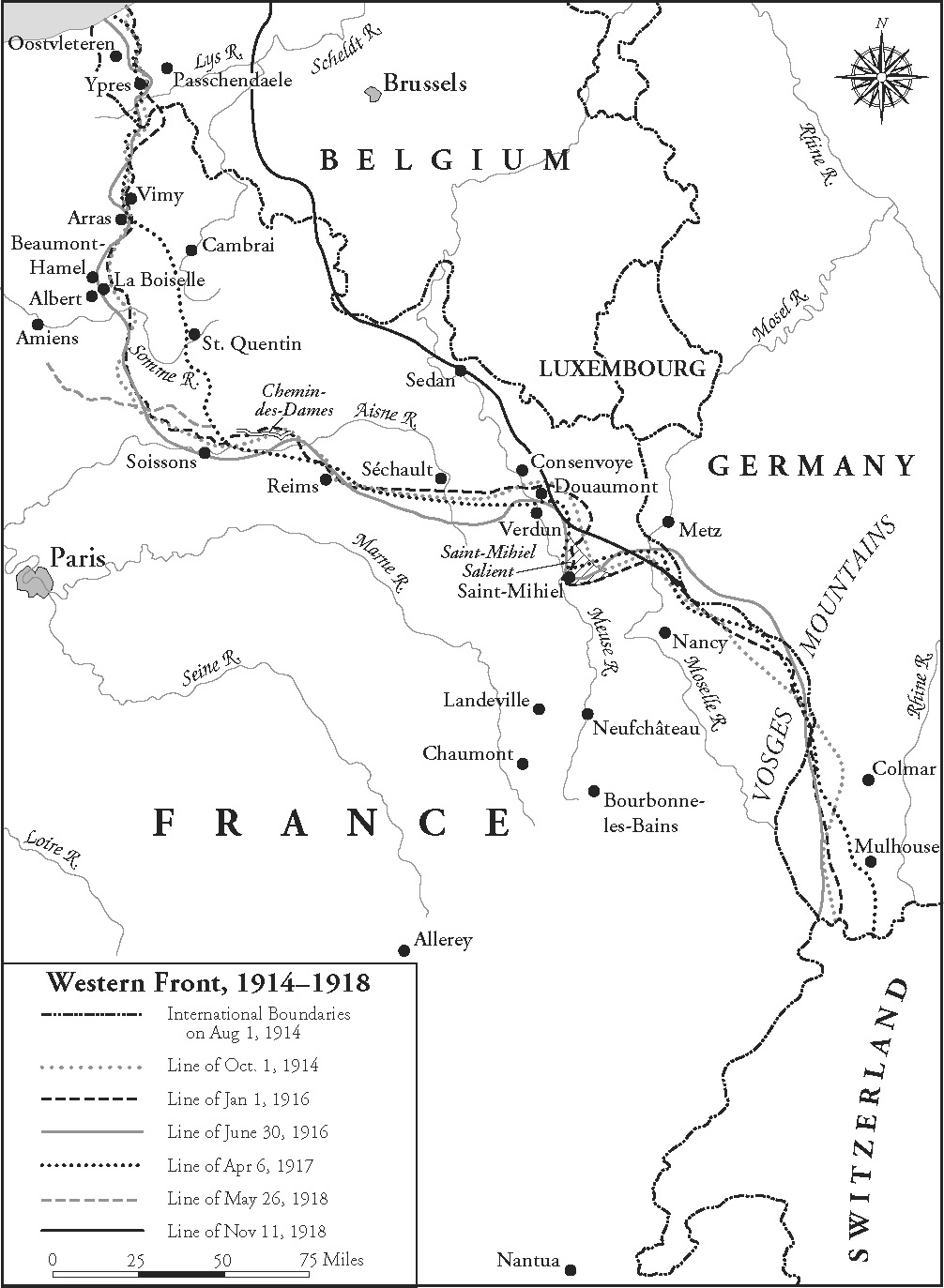

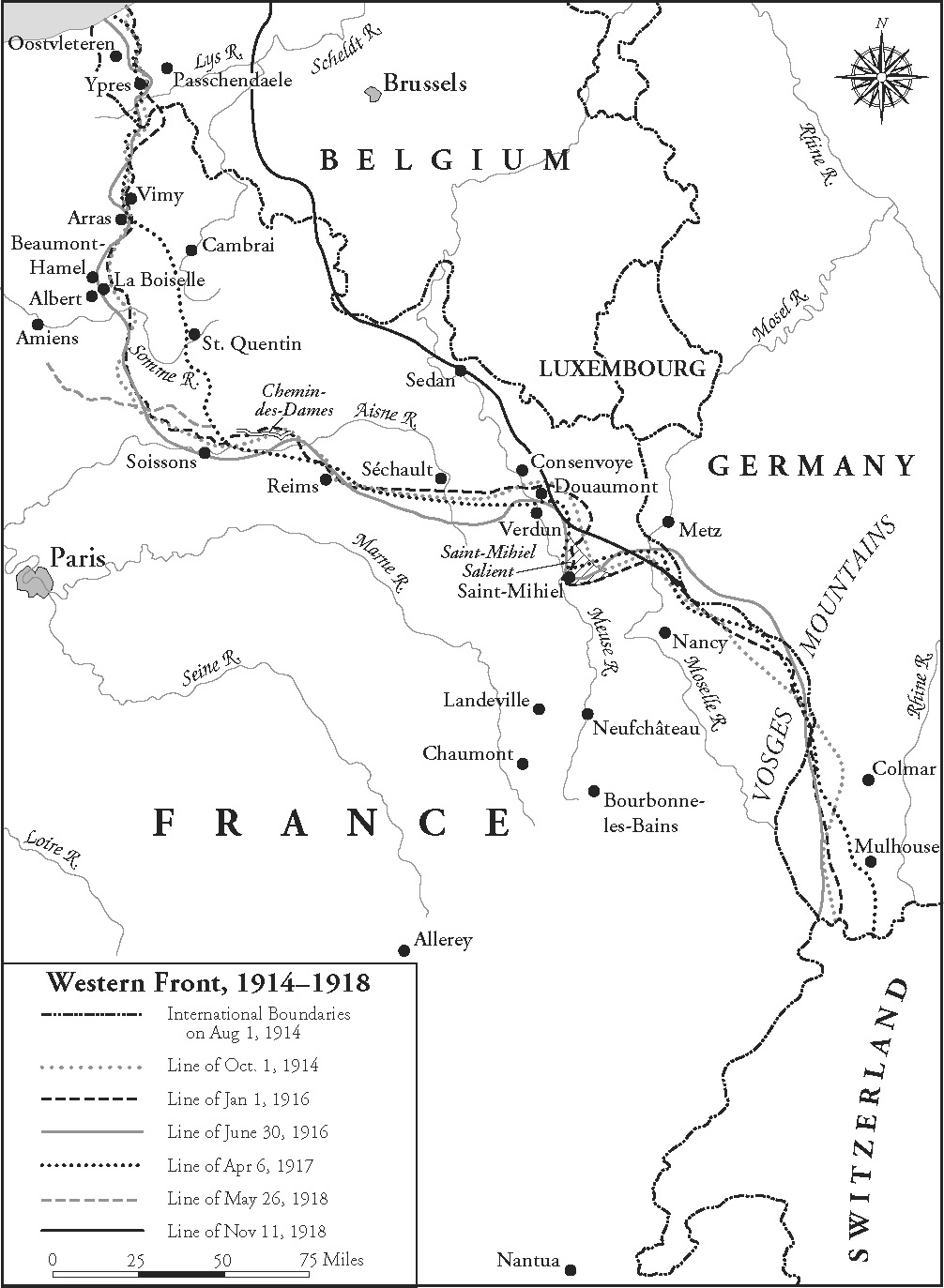

Maps

1. Western Front, 19141918

2. Seicheprey, April 20, 1918

3. The German Spring Offensive, 1918

4. Belleau Wood, June 1918

5. Saint-Mihiel, September 1213, 1918

6. The Meuse-Argonne Offensive, September 26November 11, 1918

7. The Second Battle of the Marne, July 15August 6, 1918

Prologue: No Mans Land

B EFORE THE NEW AGE and the New Frontier and the New Deal, before Roy Rogers and John Wayne and Tom Mix, before Bugs Bunny and Mickey Mouse and Felix the Cat, before the TVA and TV and radio and the Radio Flyer, before The Grapes of Wrath and Gone with the Wind and The Jazz Singer, before the CIA and the FBI and the WPA, before airlines and airmail and air conditioning, before LBJ and JFK and FDR, before the Space Shuttle and Sputnik and the Hindenburg and the Spirit of St. Louis, before the Greed Decade and the Me Decade and the Summer of Love and the Great Depression and Prohibition, before Yuppies and Hippies and Okies and Flappers, before Saigon and Inchon and Nuremberg and Pearl Harbor and Weimar, before Ho and Mao and Chiang, before MP3s and CDs and LPs, before Martin Luther King and Thurgood Marshall and Jackie Robinson, before the pill and Pampers and penicillin, before GI surgery and GI Joe and the GI Bill, before AFDC and HUD and Welfare and Medicare and Social Security, before Super Glue and titanium and Lucite, before the Sears Tower and the Twin Towers and the Empire State Building and the Chrysler Building, before the In Crowd and the A Train and the Lost Generation, before the Blue Angels and Rhythm & Blues and Rhapsody in Blue, before Tupperware and the refrigerator and the automatic transmission and the aerosol can and the Band-Aid and nylon and the ballpoint pen and sliced bread, before the Iraq War and the Gulf War and the Cold War and the Vietnam War and the Korean War and the Second World War, there was the First World War, World War I, the Great War, the War to End All Wars.

It wasnt the biggest Veterans Day parade in New England, or in Massachusetts, or even on Cape Cod, for that matter. In fact, it was rather modest: a handful or two of old soldiers and sailors in uniform, a half-dozen large flags, a few cars, a couple of cops on motorcycles, and a fife-and-drum corps comprising two or three dozen area schoolchildren dressed like Continental soldiers and playing Revolutionary Warera tunes. There were short speeches at the war memorial, salutes at the Civil War monument, and hot dogs at the American Legion Hall. All told, this celebration of Veterans Day, 2003a holiday that was first established by Congress in 1926 as Armistice Day, an observance of the truce that ended World War I at 11:00 a.m. on November 11, 1918lasted about an hour.

But the procession, modest as it was, had something else that made it unique among Veterans Day parades throughout the United States that year: Corporal Jesse Laurence Moffitt, a bona fide World War I veteran, a man who was then 106 years, eight months, and five days old. He had joined the Connecticut National Guard in February, 1917; when America entered the war, two months later, his unit became the 102nd Infantry Regiment, which was in turn part of the 26th Division, the Yankee Division, so called because it was composed entirely of regiments from New England. That summer, he shipped out for France, where he would, eventually, fight in one terrible battle after anotheruntil, on November 11, 1918, as he recalled, all firing stopped. Complete silencethere wasnt a sound at eleven oclock. And we were able to go out of our dugouts and trenches without our helmets or gas masks, which was the first time wed been able to do that since we first went to the front.

Exactly eighty-five years later, he rode in a parade in the picturesque seaside town of Orleans, Massachusetts, to mark the anniversary of that day, just as he did every year. Afterward, I asked him why, at his age, he made a point of doing so.

People like to see a World War I exhibit, he replied. I would assume that it means something to people to see a World War I veteran, because theres not many of us around, as you know. Just to be able to say that you have seen a 106-year-old is satisfying to some people. After all, its not an everyday event for most people.

I couldnt argue with that; if anything, it was a serious understatement. It had taken me several months of intensive searching to find just such a man, and several more before I found myself here, witnessing this historic occasion. And yet, as remarkable as all this was to me, I would not grasp the occasions true significance for some time to come. None of us who lined the road that morning could have known that what we were actually witnessing there in Orleans was the last small-town Veterans Day parade anywhere to feature a living American veteran of World War I.

I write these words on the island of Manhattan, the center of a city older than Boston and Philadelphia, a city that is richer in history than perhaps any other in America. That this is so often comes as a surprise to people, because New York is and always has been about what is new, not what is old; about what will be rather than what was. But just a few blocks from where I sit, mounted on the front of a small, vest-pocket Presbyterian church, there is a very large plaque listing the names of 136 members of that congregation who went off to fight in the First World War, including five who never returned. Three blocks away, inside a large Catholic church, another plaque lists the names of thirty-eight men from the parish who were killed in the same war. Across the park, almost to the East River, is York Avenue; most New Yorkers assume it is named, as is their city, for the Duke of York, but it is actually an homage to Sergeant Alvin C. York, a pacifist from the mountains of eastern Tennessee who was drafted and sent off to France, where, on the night of October 8, 1918, he single-handedly killed seventeen German soldiers and captured 132 more, a feat for which he was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, the French Lgion dHonneur, and several other high honors. Farther uptown, at the spot where Broadway and St. Nicholas Avenue converge, you will find a large bronze statue of doughboys struggling on a battlefield, mounted atop a granite monument to neighborhood boys who did the same. And up at the tip of the island, in the neighborhood known as Inwood, there are streets named for local sons who never returned from the trenches. Their last names, and the war they served in, are all that is remembered of them today.

Next page