Master of Sea Power

Master of Sea Power

A Biography of

Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King

Thomas B. Buell

With an Introduction

by John B. Lundstrom

NAVAL INSTITUTE PRESS

Annapolis, Maryland

The latest edition of this work has been brought to publication with the generous assistance of The United States Naval Academy Class of 1945.

Naval Institute Press

291 Wood Road

Annapolis, MD 21402

This book was originally published in 1980 by Little, Brown and Company, Boston.

1980 by Thomas B. Buell

Introduction 1995 by the U.S. Naval Institute, Annapolis, Maryland

Cartoon on page 138 by Jon (Corka) Cornin, 1944 by Curtis Publishing Company

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

First Naval Institute Press paperback edition published in 2012.

ISBN 978-1-61251-210-5 (eBook)

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows:

Buell, Thomas B.

Master of sea power : a biography of Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King / Thomas B. Buell ; with an introduction by John B. Lundstrom.

p. cm. (Classics of naval literature)

Originally published: 1st ed. Boston : Little, Brown, 1980. With new introd.

Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index.

1. King, Ernest Joseph, 18781956. 2. AdmiralsUnited StatesBiography. 3. United States. NavyBiography. 4. World War, 19391945Naval operations, American. I. Title. II. Series.

V63.K56B83 1995

359.0092dc20

[B]

95-3308

Print editions meet the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Print editions meet the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

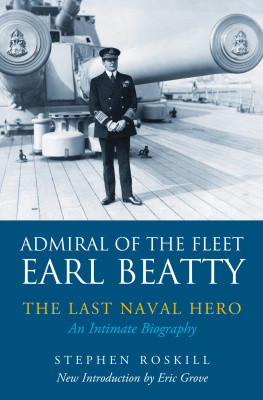

Frontispiece: Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King, Commander in Chief U.S. Fleet, and Chief of Naval Operations, 1945 (National Archives 80-G-416886)

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Marilyn, Melora, and David

Contents

Current historiography exhibits a fashionable bias toward determinism and dotes on social history. Its practitioners tend to disparage the very real impact that individuals can exert on the broad course of events, particularly at times of great crisis. In contrast, the study of warfare often flirts with a Carlylean interpretation of history that emphasizes the importance of individual commanders. Given the nature of the subject, the actual process of deciding strategy during a campaign or fighting a battle can be analyzed minutely, and the role of specific leaders carefully assessed. Obviously, the institutions that nurtured these commanders to a large extent fashioned their basic philosophy and created the weapons they wielded in battle. Yet at crucial times the particular man or woman placed on the spot can have a great influence on how an entire nation will respond to a crisis.

Following this approach, it is fascinating to contemplate how different the course of World War II might have been without the unique contribution of Fleet Admiral Ernest Joseph King, U.S. Navy, to the strategy employed by the United States in particular and the Allies in general.

On 7 December 1941, Admiral King was serving as commander in chief of the Atlantic Fleet. Thus he was free of the taint of the debacle of the Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor. Respected for his ability and toughness, King was the logical choice to revitalize the U.S. Navy and lead it to victory. On 30 December 1941 he was elevated to the restored billet of commander in chief of the United States Fleet, whose official abbreviation he insisted on changing from the uninspiring CinCUS (pronounced sink us) to CominCh.

Soon after, King acquired more control over the Navy. On 26 March 1942, while still remaining CominCh, he replaced Adm. Harold R. Stark as Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) and became the first individual to hold both posts simultaneously. In addition, a presidential order gave him unprecedented control over the Navys administrative apparatus. Especially during the tenure of Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox (who died in 1944), King enjoyed relatively little interference from his civilian superiors. Thus he became the most powerful naval officer in the history of the United States and likely the entire world. Certainly no one else has ever commanded more ships, naval aircraft, or sailors.

In addition to running the Navy, King took his rightful place on the newly established U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff and concurrently on the Allied Combined Chiefs of Staff. There he joined in the often stormy counsels that put together the grand strategy employed by the Allied coalition to defeat the Axis powers.

During 1941 while the United States was still at peace, planners from the U.S. Army and U.S. Navy worked in concert with their British counterparts. Following the lead of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his key strategists, they determined it was necessary to concentrate forces to defeat Germany and Italy before dealing extensively with any threat Japan might present. Their resulting war plan, Rainbow Five, prescribed future offensive operations in Europe and dictated a strict defensive posture in the Pacific. This was in line with Roosevelts policy of supporting Britain against Germany. He significantly weakened the Pacific Fleet (the principal deterrent against Japan) in order to fight what was essentially an undeclared war between Kings Atlantic Fleet and the German Navy. The desperate plight of the Soviet Union in its savage war with Germany gave even more urgency to this approach.

In the first months of the Pacific War, Japan blitzed through Southeast Asia, the Dutch East Indies, and the western Pacific. The stunned Allies withdrew into the Indian Ocean, the environs of Australia, and eastward halfway across the Pacific. In early 1942 despite these terrible blows, U.S. Army planners, looking always toward Europe, continued to advocate remaining on the defensive in the Pacific Theater, even accepting the loss of Australia if otherwise unavoidable given the meager forces allocated. Conversely, Army chief of staff Gen. George C. Marshall pressed for a massive buildup in England to conduct in the summer of 1942 an amphibious offensive across the English Channel into France.

To King, such passivity in the face of the surging Japanese was totally unacceptable. His long experience as a naval strategist argued that the best defense was a good offense. He knew that it was imperative to seize the initiative from the Japanese and attack before they could advance further or consolidate their hold on their newly gained territories. King also felt that the strident calls for a general European offensive were premature, given the time needed for the United States to mobilize its military strength. Therefore, during this long, unavoidable buildup, some of the massive resources earmarked for eventual use in Europe would be much more effective if used immediately in the Pacific.

Next page