Contents

ALSO BY MARY V. DEARBORN

Mistress of Modernism: The Life of Peggy Guggenheim

Mailer: A Biography

Queen of Bohemia: The Life of Louise Bryant

The Happiest Man Alive: A Biography of Henry Miller

Love in the Promised Land: The Story of Anzia Yezierska and John Dewey

Pocahontass Daughters: Gender and Ethnicity in American Culture

This Is a Borzoi Book Published by Alfred A. Knopf

Copyright 2017 by Mary V. Dearborn

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Dearborn, Mary V., author.

Title: Ernest Hemingway : a biography / Mary V. Dearborn.

Description; 1st ed. | New York : Knopf, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016015837 | ISBN 9780307594679 (hardcover) ISBN 9781101947982 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : Hemingway, Ernest, 18991961. | Authors, American20th centuryBiography.

Classification: LCC PS 3515. E 37 Z 5849 2017 | DDC 813/.52 [B]dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016015837

Ebook ISBN9781101947982

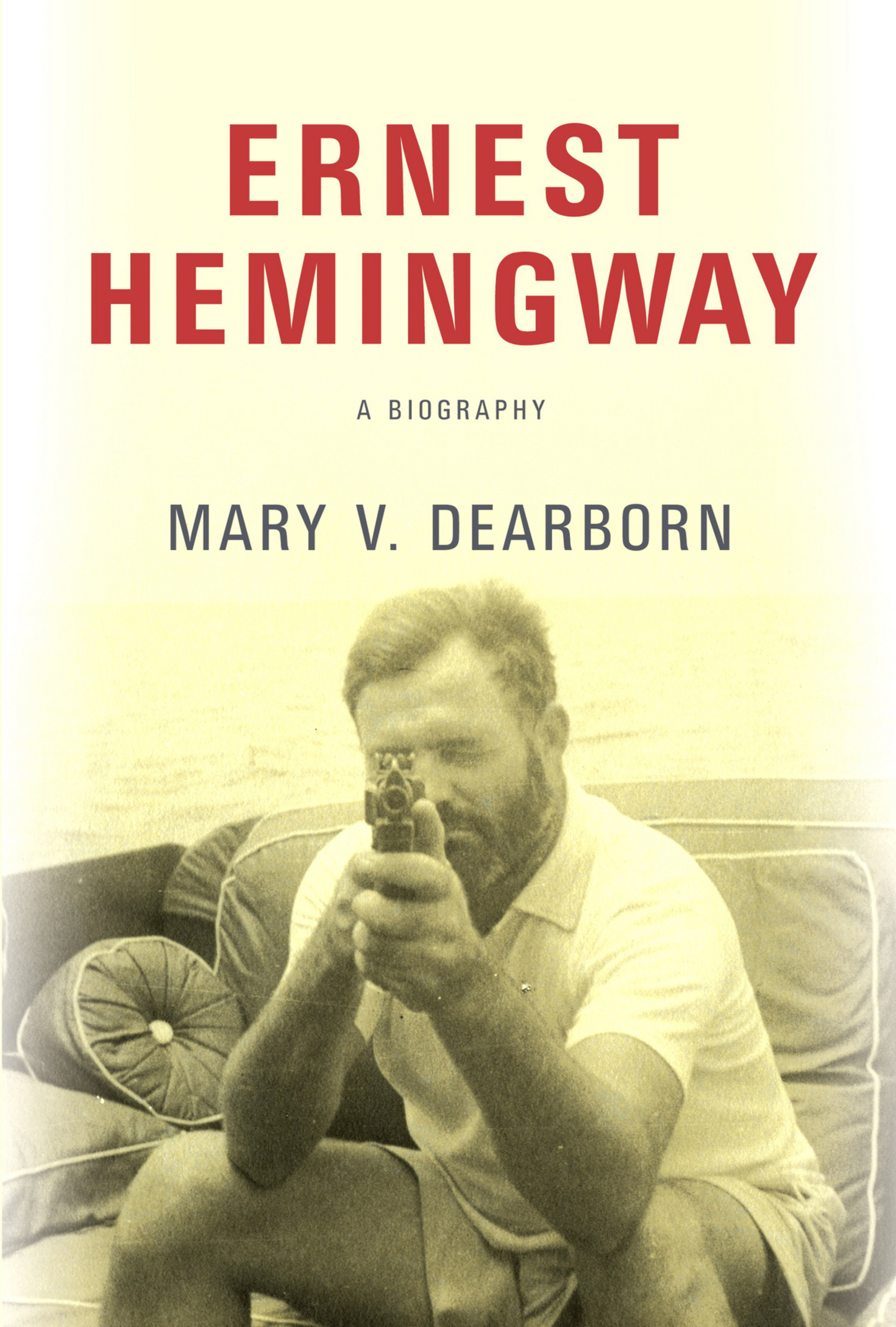

Cover photograph: Ernest Hemingway Collection, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum

Cover design by Janet Hansen

v4.1_r1

a

FOR ERIC AND FOR BETH

Contents

Prologue

O ne evening in the mid-1990s I attended a panel on Ernest Hemingway and his work at New Yorks Mercantile Library. The Mercantile was known for lively programming arranged by its then director, Harold Augenbraum, and this evening was no exception. Hemingway had been somewhat under fire of late. A controversial 1987 biography by Kenneth Lynn had left Hemingway fans reeling with the revelation that Ernest had been dressed as a girl in his early years, which Lynn argued had shaped the authors psyche and sexuality.

The previous year Hemingways posthumously published novel, The Garden of Eden, had revealed a writer seemingly obsessed with androgyny, its hero and heroine cutting and dyeing their hair to become identical, beyond genderjust as in the explicit sex scenes they move beyond traditionally male and female roles. At roughly the same time, Hemingway and his place in the Western literary tradition came under full-on attack, as readers, scholars, educators, and activists urgently questioned what dead white males like Hemingway had to say to us in a multicultural era that no longer accords them automatic priority. The so-called Hemingway codea tough, stoic approach to life that seemingly substitutes physical courage and ideals of strength and skill for other forms of accomplishmentincreasingly looked insular and tiresomely macho.

That night at the Mercantile Library, these issues were roiling the waters. Should we still read Hemingway? Are his concerns still relevant? Was Hemingway gay? (The short answer is no.) Why could he not create a complicated female heroine? Does Hemingway have anything at all to say to people of different races and ethnicities? On the plus side, does his intense feeling for the natural world take on greater significance at a time of growing environmental consciousness? If we were to continue to read Hemingway, we needed to take note of how we read him, it seemed.

The discussion after the panel was animated. The moderator called on a burly man with a peppery crew cut. I recognized him as a professor and critic who wrote about the literature of the 1920s, especially Hemingways friend F. Scott Fitzgerald. I just want to say one thing, he stood up and announced. Hemingway made it possible for me to do what I do.

I thought about what he said for a long time afterward. He seemed to mean something very specific and personalsomething to do with reading literature and writing about it as a vocation. He was not talking about teaching or making money. He was talking about whether writing was an acceptable occupation for a man, both on his terms and the worlds. Hemingway, not only in his extraliterary pursuits as a marlin fisherman, a big game hunter, a boxer, and a bullfight aficionado but also in his capacity as an icon of American popular culture, was the very personification of virilityand he was a writer. Any taint of femininity or aestheticism attached to writing had been wiped clean.

I was reminded of a rather extraordinary statement made late in life by the writer Harold Loeb, the model for Robert Cohn in Hemingways first full-length novel, The Sun Also Risesthe lover of Lady Brett Ashley who proves himself a wet blanket during the Pamplona bullfighting fiesta. It was hardly a flattering portrayal, but Loeb had not forgotten why he, like so many others, had been drawn to Hemingway when they both were young: I admired his combination of toughness and sensitiveness.I had long suspected that one reason for the scarcity of good writers in the United States was the popular impressionthat artists were not quite virile. It was a good sign that men like Hemingway were taking up writing.

As I went on to think and write about Hemingway myself in the period following this panel, I thought I understood the critics remarks that evening. But I couldnt account for the risky, emotional, and highly personal nature of his confession. What I couldnt understand was his passion. It seemed to me that something was being said here about being a man and a writer, and it made me feel excluded.

There is no shortage of Ernest Hemingway biographiesone of them runs to five volumes. His first biographer, Carlos Baker, set the bar in 1969, and the efforts of most of those who followed have been impressively researched and, for the most part, insightful. There has not yet been a biography written by a woman. This doesnt necessarily mean that much; mainly, I find that I am interested in different aspects of Hemingways life from the ones that drew his previous (male) biographers. I shrink from describing what aspects those are: Id rather not encourage the notion that men and women see things in fundamentally different ways. By definition, studying Hemingway is about the rough opposite, the cultural construction of genderhow sex roles are determined by the forces around us rather than our genes. It is through figures like Hemingway that masculinity gets definedeven if that same cultural construction affects him in turn.

Before turning to Hemingway, I wrote biographies of two major writers who also helped define American masculinity through both their lives and their fiction: Henry Miller and Norman Mailer. Himself a (later) expatriate in Paris. Miller curiously never spoke of Hemingway, though Miller, like Hemingway, livedfrom the outside, that isa life that is the stuff of many a male fantasy. Mailer was a great admirer of both Miller and Hemingway; while he may have enjoyed Millers work more, he considered Hemingway easily Americas greatest living writer. Yet he seemed to recognize that somewhere along the way, Hemingways work and life became onethat without Hemingways image of a ruggedly physical man of action, the work would not be the same. Mailer asked us to acknowledge how silly