Also by Nick Bunker

Making Haste from Babylon:

The Mayflower Pilgrims and Their World

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2014 by Nick Bunker

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House LLC, New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto, Penguin Random House companies.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

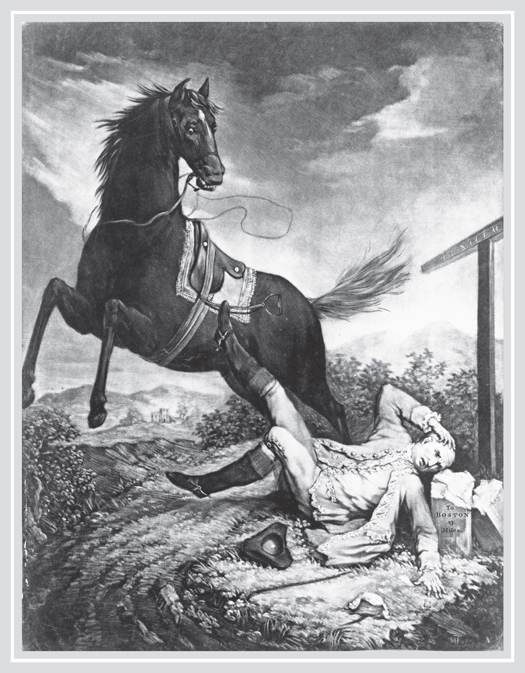

F RONTISPIECE: Published in London in September 1774, this print engraved by the Irish artist John Dixon uses the image of a horse throwing its rider on the road between Boston and Salem, Massachusetts, to symbolize colonial resistance to Great Britain, with the horseman representing the imperial government. Library of Congress

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bunker, Nick.

An empire on the edge : how Britain came to fight America / Nick Bunker.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-307-59484-6 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-0-385-35164-5 (eBook)

1. United StatesHistoryRevolution, 17751783Causes. 2. United StatesHistoryColonial period, ca. 16001775. 3. United StatesForeign relationsGreat Britain. 4. Great BritainForeign relationsUnited States. 5. Boston Tea Party, Boston, Mass., 1773. I. Title.

E210.B94 2014

973.3dc23 2014001032

Front-of-jacket photograph The Battle of Lexington by Alonzo Chappel. Superstock.

Jacket design by Stephanie Ross

v3.1

This book is dedicated to my wife, Sue Temple,

with love and gratitude

The rulers of Great Britain have, for more than a century past, amused the people with the imagination that they possessed a great empire on the west side of the Atlantic.

A DAM S MITH , The Wealth of Nations (1776)

Contents

P ROLOGUE

One

T HE F INEST C OUNTRY

IN THE W ORLD

Let the savages enjoy their deserts in quiet.

T HOMAS G AGE, COMMANDER IN CHIEF OF THE B RITISH ARMY IN A MERICA

In the summer of 1771, the Mississippi River marked the western boundary of the British Empire.

A few miles from the waters edge, in the furthest corner of what is now the state of Illinois, a traveler brave enough to venture overland from the east would come to a tall, rocky bluff, pitted with caves and crevices among the trees. Reaching the top he would look down across a wide and muddy tract of land filled with corn and ripe tobacco. Beyond the fields and just before the river, his gaze would fall upon a line of battlements built with limestone quarried from the ridge. They belonged to a fort with platforms for cannon at each corner and a British flag flying above it. As the traveler crossed the plain, more details would emerge from out of the haze. He would see a moat, a sloping earthwork, and a row of huts near the fort, with the smoke from kitchen fires hanging in the sunshine.

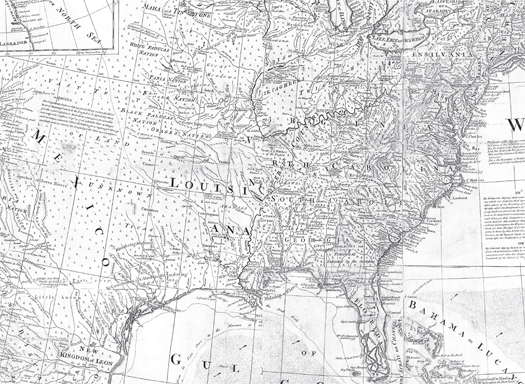

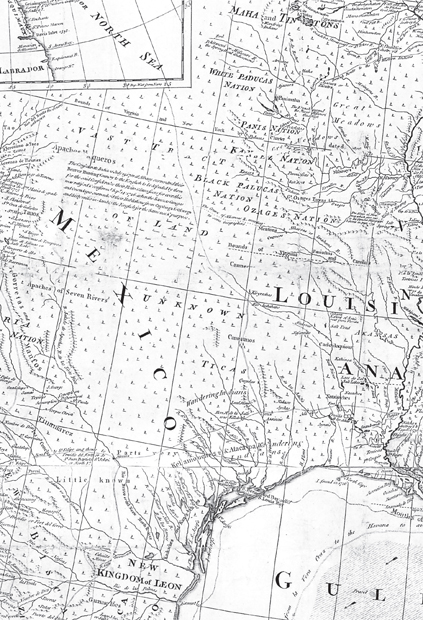

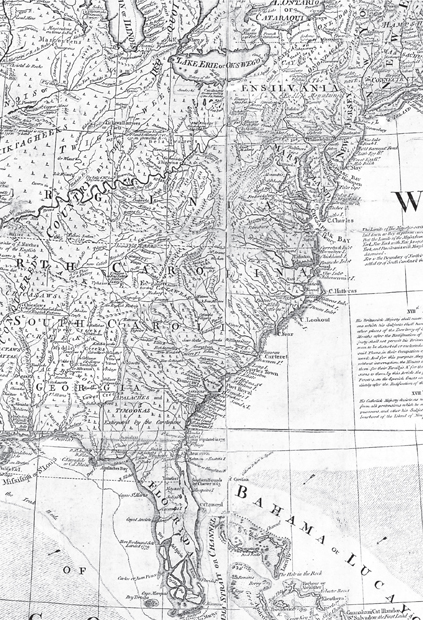

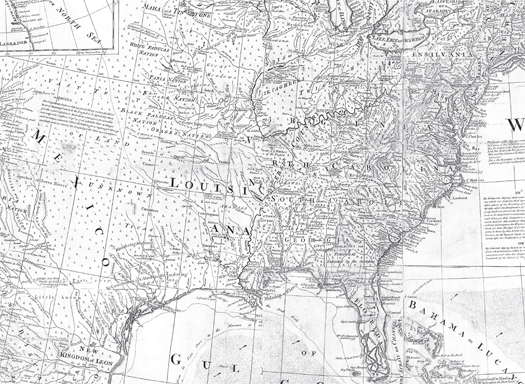

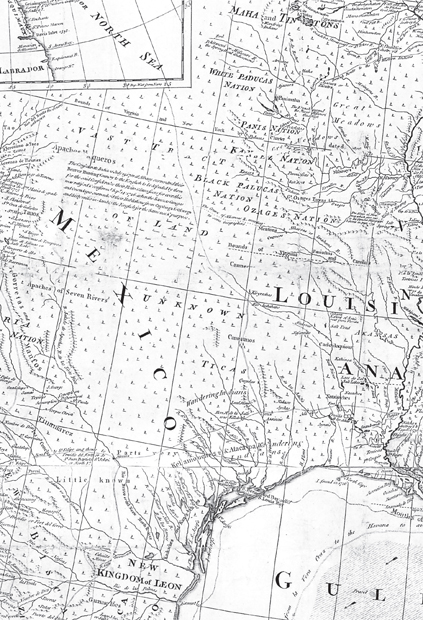

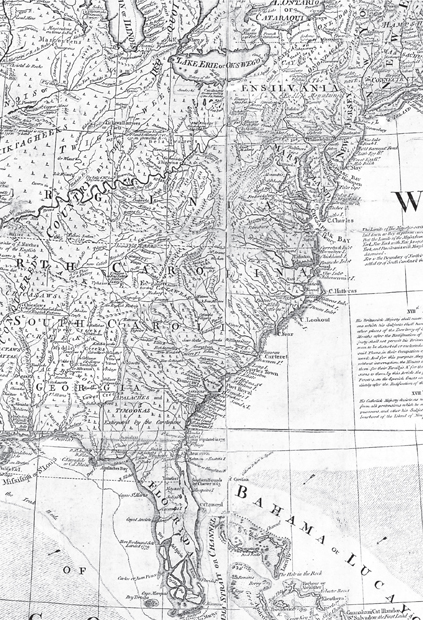

The North American interior as the British saw it in the 1760s, in a map drawn up for George III after the defeat of France in the Seven Years War. All the newly conquered territory west of the Appalachians was set aside for the Indians. The shading from north to south along the mountains represents the Proclamation Line, beyond which settlers were not supposed to pass. Fort de Chartres was located on the Mississippi, to the right of the V in Virginia, about forty miles south of St. Louis. British National Archives, Kew

From a distance the forts defenses seemed solid enough, but the traveler would soon identify odd traces of neglect. Nobody had cut the tall grass by the gate. Heaps of rubble lay beside the track, all that was left of a village or a few abandoned farms. Some broken fences remained, but the cattle they corralled had vanished long ago; the corn was running wild; and many years had passed since a field hand took a harvest of tobacco leaf. In the dusk, the traveler might exchange a greeting with the redcoats who stood sentry in this corner of the wilderness. They would offer him some rum and show him around the back of the fort, where he would find more evidence of decay. Close to the walls, the riverbank dipped away steeply in a cliff of yellow sand. From time to time parts of it crumbled and fell, to be carried off by the Mississippi in the night.

Far away at army headquarters in New York, the base by the river was officially listed as Fort Cavendish, after an English general of noble blood who never found time to cross the Atlantic. On the frontier, the redcoats chose to keep the name the French had given to the place. To a Frenchman, the post was known as Fort de Chartres, mispronounced by the British as Fort Charters. By the early 1770s, it was slipping into ruin like the rest of the imperial system to which the base belonged. From the French, the British had inherited a post constructed on moist, low-lying ground, close to a bayou and next to a swamp, in a site so exposed that the walls needed constant repair until at last they fell apart entirely. Handsome to look at but far too costly to maintain, the fort was built on weak foundations, the British had acquired it without a cogent plan for its future, and in time it was bound to collapse. In other words, the post symbolized Great Britains plight in North America as a whole, a continent she did not comprehend and could not hope to rule in its entirety.

In theory, Fort Charters controlled a long line of communication from Lake Michigan down to the Gulf of Mexico. In practice, the authority of King George III stretched no further than a field gun could fire six pounds of iron from the ramparts. Much the same was true in the rest of his American dominions, where his position would soon become almost as untenable as the fort.

In the story of what happened to the British in Illinois, we can find a parable about the vanity of empire. It was a tale of error and misunderstanding, of ideas only half thought out, of neglect and delay and occasional corruption. The occupation of Fort Charters would end in failure after a pitiful waste of lives and money: a foretaste of what was to come when, soon afterward, the British lost not only the Mississippi valley but also the loyalty of their old colonies along the eastern seaboard, as the American Revolution started to unfold.

The British involvement in the far west had begun in 1763, by the stroke of a pen at a conference in Paris. A treaty negotiated at the Louvre put an end to the Seven Years War, a conflict fought out on three continents between France, Spain, and Austria on the one hand, and Great Britain and its Prussian ally on the other. In exchange for peace the French king Louis XV ceded away a string of islands in the Caribbean and all his possessions on the frontier from Quebec to Alabama. Suddenly the British acquired a vast new domain beyond the Appalachians: a territory so immense that two more years passed before they could hoist their colors above every post the French had surrendered.