N owadays, if you have a few pounds to spare, you can buy a copy of The Times, printed on the day you were born. Leafing through the pages, you glean something of the world as it was at the time of your own arrival. You see recorded the lives of those who made your world, their interests and values, what motivated them, and what they feared. You see the world that has shaped and bordered your life and, in significant measure, made you what you are.

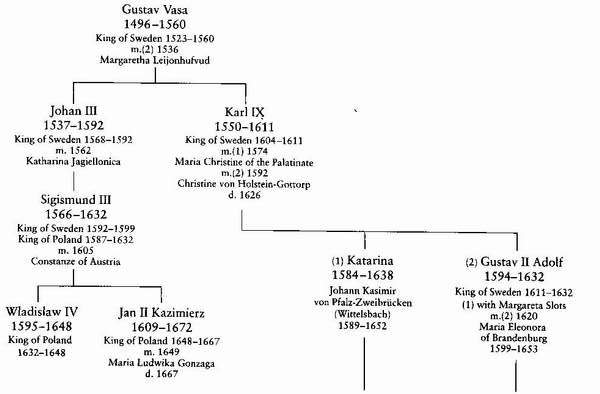

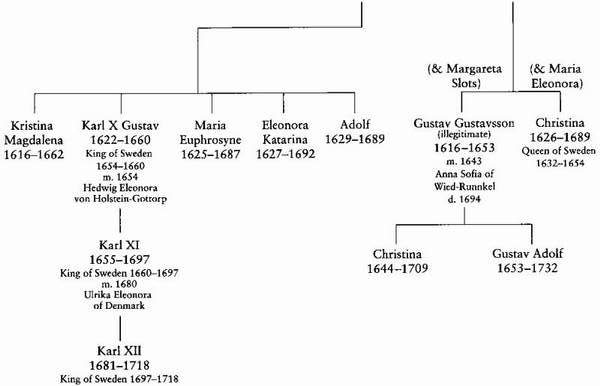

What, then, was Christinas world? What forces shaped her; what ideas framed her mind? She was born in 1626, into a world overwhelmingly European, though the bounty and burdens of the great era of exploration had opened its eyes to other lands beyond. American silver framed the holy icons of the pious, and the soft white hand of many a countess sparkled with jewels from the East, while the first African indentured servants had begun their woeful voyage aboard a Dutch cargo ship. Knowledge had come, too, with the diamonds and the silver, but Europes gentleman-travellers still seldom ventured to very distant shores in search of it. It was left to the sailors and traders and priests to make the longest journeys, and to bring the tales back home.

Christinas was a cold world, the coldest time Europe had known for thousands of years, the Little Ice Age which balked the harvests and froze the seas. Fires blazed on ice-thickened rivers, and birds were seen to drop from the skies in mid-flight, frozen to sudden death. Christinas world was a dirty world of sudden illness and doubtful water and scanty, tainted food, where peasants and beggars faced hunger as routinely as the sunrise. It was a mans world, where women had little public power; high rank might soften the outlines, but too frequent childbirth was most womens lot. And it was a familiar world, a world of small towns where great families ruled, where faces were known and strangers few, and secrets hard to keep.

Above all, Christinas world was a world at war, the great Thirty Years War which raged across Europe from 1618 to 1648, claiming countless lives, including that of her own great father. Christina would grow quickly accustomed to it; during the whole of her life, Europe would know barely a single year of peace. Warfare in her world was a normal aspect of government. States and empires grew from it in a savage symbiosis, filling its maw with their choicest fruits, and drawing new wealth from its wake. Christinas contemporaries accepted it as a fact of life, and reserved their greatest praise for those who waged it successfully.

The finest laurels were still worn by the Habsburg Empire of Spain, whose brilliant armies had dominated Europe for more than a hundred years. But, fearful of new ideas and disdainful of trade, Spain had now begun its long decline. The new road was being paved by its vibrant little brother along the western shores of the continent; in the energetic, enterprising provinces of Holland, the ships and banks and warehouses of a new commercial prosperity were busily being built. Within a few decades, Spains political laurels would pass to France, whose brilliant star had yet to rise, and its military honours were even now being captured by Sweden itself, whose innovative armies, seemingly invincible, had pressed deep into Europe, captained by their own splendid King.

The Swedes great enemy was the Austrian Habsburg Empire, a vast Catholic power which stretched from Poland to the Czech lands and from Bavaria to Croatia. Since the infamous defenestration of Catholic officials in Prague in 1618, the Empire had been at war, alternately desultory and ferocious, with various Protestant powers. The many German lands which were not within its borders stood as independent states, either Catholic or Protestant, numbering in their confusing hundreds.

No single land of Italy existed, but the marvellous Italian cities, Europes most fabulous jewels, still dazzled eye and mind after centuries of cultural pre-eminence. Their most gifted sons had made their way to every corner of the continent, leaving the fruits of their artistry in marble and on canvas, changing perspectives, opening minds, firing the imagination. The papal city of Rome itself had recently enjoyed a great artistic renaissance, encouraged and funded by successive popes intent on re-establishing the primacy of Catholicism after the Protestant Reformation.

England, though not isolated from European life, remained as yet peripheral. Its new King was beginning to set out his claim to absolute rule by divine right, an idea that would spark revolution, and in time engender the downfall of Christinas world. The Kings nemesis, Oliver Cromwell, was a young country gentleman, still unknown. Shakespeare had lain just ten years in his grave.

To the east, the first Romanov Tsar sat upon the throne of Muscovy. After its long Time of Troubles, Russia now looked forward with hope, but for decades to come it would be outshone by its dual neighbour, Poland-Lithuania, the largest state in Europe, and Swedens longstanding threat from the east. And southward, linking Sweden with the mainland over the much-disputed Baltic Sea, lay the ancient enemy and former ruling power of Denmark.

Despite its military prowess, Sweden itself was undeveloped. In economic and social terms, it was essentially still a medieval land, overwhelmingly rural, exporting its ablest youth to more promising environments, and relying on foreigners for capital and enterprise at home. Throughout the country a series of cold fortress castles, grim stone on the outside and bare-walled inside, contained what little the kingdom possessed of scientific endeavour or cultivated living. But the war booty of recent years had at last allowed it to begin its ascent into the light of culture and learning, and in the 21 years of his youthful reign, Christinas brilliant father would succeed in dragging and thrusting his backward homeland into the very heart of European life.

Christinas world was a world of vibrant learning, of philosophy and poetry, of religious scholarship and scientific experiment. It had begun its long, deep love affair with the world of classical antiquity, now resurgent after the exotic lures of the great age of exploration; on the foundations of this ancient world new temples were being built to Greek thinking and the manly virtues of Rome. Renaissance ideas persisted, too, not least in the widespread practice of alchemy, consuming fortunes and lifetimes in a misbegotten search for truth.

And, while Europes princes fought among themselves, their Christian world faced two mightier enemies, from without and from within. The external threat was the great Ottoman Empire of the Turks, which at Christinas birth stretched from Algiers to Baghdad and as far west as Budapest. Late in her life she would hear of a vast Turkish army pitching its tents at the very gates of Vienna. But it was the internal enemy that in the long run would prove the more decisive. With their stumbling, excited experiments, Europes natural philosophers had begun their challenge to religious orthodoxy. With increasing success, they now strove to provide materialist explanations of the natural world. Though most were repaid with hostility and persecution, and some even with death, no Church, and no state, could stop them. The great march of empirical science had begun, and all ears, willing and unwilling, heard the beat of its tremendous drum.