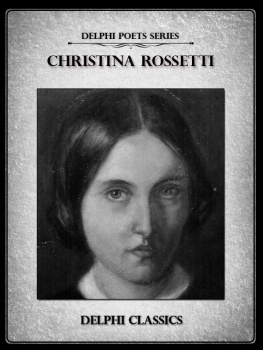

A S SHE LATER recreated in her own nursery poem, Christina Rossettis earliest memory was of her father crowing like a cock to wake his children:

Kookoorookoo! Kookoorookoo!

Crows the cock before the morn;

Kikirikee! Kikirikee!

Roses in the east are born.

Kookoorookoo! Kookoorookoo!

Early birds begin their singing;

Kikirikee! Kikirikee!

The day, the day, the day is springing.

It came of course, from Italian, as she recaptured when translating her verse back into her fathers tongue:

Cuccurucu cuccurucu

All alba il gallo canta.

Chicchirichi chicchirichi

Di rose il ciel sammanta.

Nursery memories also included childish versions of other animal noises made to amuse the youngsters donkeys braying, pigs grunting , geese hissing. Born and reared in London, the Rossetti children heard real farmyard sounds only when staying with their grandparents in the country, where, at the age of one, Gabriel was scared by the mooing of a real-life cow.

Our first recorded glimpse of Christina is in the country, aged eighteen months, when her father pictured his skittish baby daughter, with rosy cheeks and sparkling eyes, taking tentative steps in the garden like a little butterfly among the flowers and currant bushes. It was time Christina be weaned, he suggested, though there was no other baby on the way.

As the youngest, she was cradled at the breast while the older children played, with that sense of utter security later invoked in her childrens verses, Sing-Song:

You are my one and I have not another;

Sleep soft, my darling, my trouble and treasure;

Sleep warm and soft in the arms of your mother,

Dreaming of pretty things, dreaming of pleasure.

Soon, she would learn her first words. When their mother reported the amusing sayings of the other children, their father promised picture books and a box of figs, to reward their good behaviour and satisfy their small greed. The picture books contained traditional rhymes like Ding, dong, bell and Ladybird, ladybird, whose echoes fill Sing-Song, while a faint memory of the figs also reached its pages:

Currants on a bush,

And figs upon a stem

And cherries on a bending bough

And Ned to gather them.

At home, Christinas brother William recalled, their plump, balding, good-humoured father would often take a child on his knee and clap their hands together, repeating with his Italian intonation and clear-cut delivery, the pat-a-cake, pat-a-cake rhyme, transformed in Sing-Song into lines whose accompanying gestures may easily be imagined:

Mix a pancake,

Stir a pancake,

Pop it in the pan;

Fry the pancake,

Toss the pancake

Catch it if you can.

The Rossettis lived in central London, in a tall house behind the grander Portland Place, a short walk from the newly-opened Regents Park. No. 38 Charlotte Street had no garden, so the children played indoors, and in a family with four children born within five years, there was naturally much squabbling and crying. Hop o my thumb and little Jack Horner, What do you mean by tearing and fighting? asks Sing-Song in hornbook mode. William was the least assertive of the four in his own words, a demure little boy, not quarrelsome and not teazing. To his mother he was my own Willie-wee, and his childhood ambition was long-remembered:

Little Willie in his heart

Is a sailor on the sea,

And he often cons a chart

With sister Margery.

Maria, nicknamed Maggy, was an energetic and bossy big sister, rising four at the time of Christinas birth. She learnt to read and write early, a jealous edge to her warm disposition no doubt sharpened by having three siblings born in quick succession. She made the most of her superior knowledge and was always regarded as the cleverest child, who might have topped us all, as Gabriel recalled, and as she remained to Christina. In respect of sex, looks and behaviour however, Maria was outdone by Gabriel, Christina and William respectively, and in all other ways she was challenged and eclipsed by Gabriel a fiery spirit not lightly to be rebelled against; in Williams words: in anything wearing the garb of mischief he counted for all, and Maria for nothing. A charming as well as favoured eldest son, he dominated the nursery, encountering no opposition , and little resentment. He was also precociously gifted: one day in 1834 the milkman expressed astonishment at such a baby making a picture!, as he sat scribbling in the hallway. Mamma carefully kept the drawing, of a toy rocking horse, as she did all their youthful productions, in what Christina later called her proud maternal store.

Christina and William, with just over a year between them, were small allies against their teasing and often imperious elders. But Christina was also aligned with Maria by gender and, perhaps more enticingly, with Gabriel by a shared spiritedness. Where William was placid, pretty little Christina was volatile and fractious: hardly less passionate than Gabriel and more given to mere tantrums, with a formidable will. Their father called her an angelic little demon, and in 1836 wrote of her and Gabriel with their mother in the country as two little rascals brawling and bawling, while at home Maria and William were good as gold. Gallantly he offered to exchange the two storms for two calms.

But vehemence in Gabriel was considered snappishness in Christina . From infancy she had a reputation for wilfulness and temper, lamented by her father despite a certain admiration for her spirit. Before she was two years old, he compared her lack of docility to the recalcitrant House of Lords, unwilling to pass the 1832 Reform Bill. They will make all the outcry and resistance that Cristina is wont to make when you force her teeth, medicine glass in hand he wrote, but what is the end of the performance? Cristina gulps the medicine. She remembered this in Sing-Song, with Papas voice echoing in the Italian version:

| Baby cry | Ohibpiccina |

| Oh, fie! | Tuttoatterita! |

| At the physic in the cup: | Lamedicina |

| Gulp it twice | Beverside |

| And gulp it thrice | Uno,due,tre, |

| Baby gulp it up. | Edfinita. |

Toys included the little rocking horse, a spinning top, ninepins and a teetotum like a large dice with letters. The girl had dolls, and a treasured dolls tea-set, but from an early age the children were most happily occupied with colouring books and penny plain theatrical prints. Partly with an educational purpose there were card games like beggar-my-neighbour, which Williams memory linked to arithmetic, for in Mammas hands, games and pictures were usually more than play, and Sing-Song contains several learning rhymes to teach children about time, or the months of the year, or the coins of the realm:

What will you give me for my pound?

Full twenty shillings round.

What will you give me for my shilling?

Twelve pence to give Im willing.

What will you give me for my penny?

Four farthings, just so many.

Numbers came in rhyme, too, as did colours, starting with a pink rose and ending with just an orange! that is like nothing else. All around Christina, in her baby years, there was such instructional rhyming.

Letters soon followed, in alphabet verses like her own, running from Antelope and Bear to Zebra and Zebu. Y was a yellow yacht or, according to Papa, noting that the letter was unknown in Italian, the shape made by the cat as she stretched her paws on the fender before the fire.