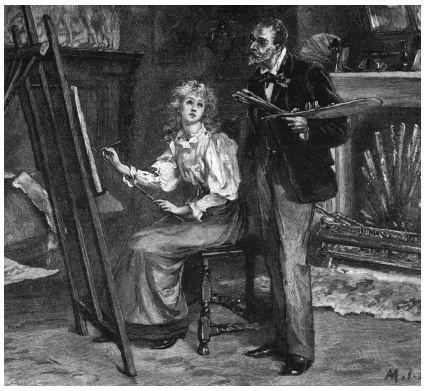

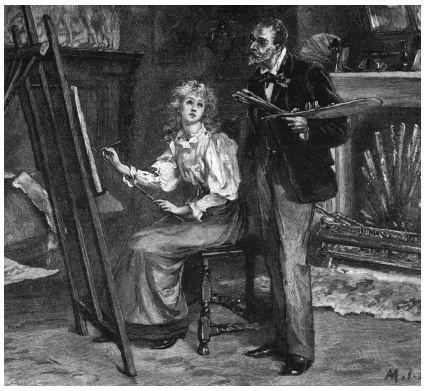

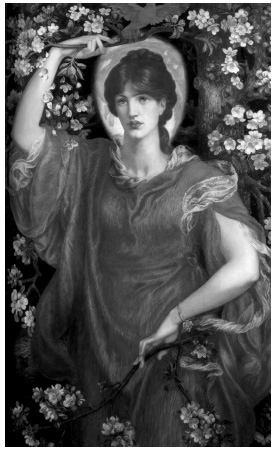

The ideal student, from a male point of view

First published in Great Britain in 2011 by

REMEMBER WHEN

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Russell James 2011

ISBN 978 1 84468 095 5

eISBN 9781844687305

The right of Russell James to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset by Phoenix Typesetting, Auldgirth, Dumfriesshire

Printed and bound by CPI UK

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword

Aviation, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Wharncliffe

Local History, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics, Leo

Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

Introduction

Long before Victoria died the nations top artists, like modern pop stars, were fabulously rich, lived in mansions, and surrounded themselves with luxury. They were household names. Outside the top bracket, artists struggled or starved; some drank themselves to death, some overdosed on drugs, others died lonely and disillusioned. The pop world again. Some had tangled love affairs, a few of which were played out and lapped up by the public. And most artists, for all their dilettante lifestyle, worked far harder at their craft than they let on; many were more commercial than they let on; they had managers, agents, supporters and promoters, and they displayed their talents in prestigious venues. They were in the entertainment business.

In this guide we look at some 400 artists, from the famous to the long forgotten, from the classical to the advanced and we look as much at the artists lives as at their canvases. Who were they? How did they live? Why do so many of us today warm to nineteenth-century art, liking it more than we like art from any other century, including our own? Is it just nostalgia or is it that the pictures Victorians produced were, to put it simply, very, very good?

Art books tend to ignore artists models, despite their being close, often intimately close, to the artists who painted them. But in this book models are brought into the light and have a chapter to themselves. They and all the artists, famous and obscure, are listed in the index, though in the book I have arranged artists by the type of work they produced. Many indeed, most artists cannot be classified into one single category; artists experiment, they change. Though most, at some time, painted portraits, I have put into the Portraits section only those best known for portraiture. Similarly with the other sections. Was Landseer a Landscape or an Animal Life painter? Though Holman Hunt was a Pre-Raphaelite, shouldnt he be seen also under Religion and Foreign Climes? Several artists Ive called Fairy Painters might be surprised, even disappointed, to see themselves listed in that chapter; wasnt Fairy painting an incidental part of their art? Not, I suggest, if it is for Fairy painting that they are best known today. Though every one is in the index, I hope youll turn to certain chapters first: the chapters that interest you, and where youll discover, perhaps, that if you like the works of Alma-Tadema, you might want to look for Ernest Normand. And have you met Normands wife?

Chapter One

THE PRE-RAPHAELITES

Back to the Future

Stephen Spender, in his article The Pre-Raphaelite Painters (1945), called Pre-Raphaelitism the greatest artistic movement in England during the 19th century. Few can disagree that, in Britain at least, it was the most influential. How did it begin, and what did it achieve?

In the late 1840s, at Londons Royal Academy Schools, the brightest star hed entered as a child prodigy was John Everett Millais, the youngest ever student and one from whom much was anticipated. Millais had befriended a fellow student, Holman Hunt, as had another student, Gabriel Rossetti. Less conscientious and already a rebel to the Academy, Rossetti had quit to become an awkward pupil to the slightly older (and equally rebellious) Ford Madox Brown. Hunt and Millais were already bosom friends when, in August 1848, Rossetti met with them in Millaiss comfortable Gower Street house (where he lived with his parents) and, while looking at a book of engraved early Italian frescoes, the three young men talked up the idea of an art student rebellion, in which they would reject the stuffy dictates of the Academy but, rather than carve a new niche as students like to do, they would rediscover the sharp and sincere simplicity of medieval painting before what they saw as its corruption through the stultifying polish of Raphael. They would emulate early masters; they would throw out contemporary rules and conventions and, instead of producing studio pictures applauded by the Academy, would work directly from nature to reveal truth.

Rossetti, ever impulsive, invited what can only be called a motley band to join them: a budding sculptor, Thomas Woolner; an art student, James Collinson; one of Hunts students, F G Stephens; and Rossettis brother William who had never made any great claim to be an artist. The group drafted a Pre-Raphaelite manifesto (which in retrospect seems remarkably tame):

1. To have genuine ideas to express

2. To study Nature attentively, so as to know how to express them

3. To sympathise with what is direct and serious and heartfelt in previous art, to the exclusion of what is conventional and self-parading and learned by rote

4. And most indispensable of all, to produce thoroughly good pictures and statues .

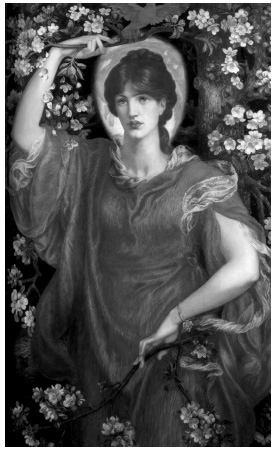

Laus Veneris by Burne-Jones (18738)

They would declare their intentions at the following years RA Exhibition, they decided, with works to astound the world. So far, so very student rebellion. Not for them still-lifes or unpopulated landscapes. For the 1849 Exhibition Millais prepared Isabella , a scene from Keats, Rossetti The Girlhood of Mary Virgin and Hunt a scene from a Bulwer-Lytton novel ( Rienzi , in which Rossetti and Millais were his models). Each painting would bear the initials PRB (Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood). Rossetti, true to form, pulled out, and displayed his picture instead at the Free Exhibition in a minor gallery in Hyde Park. But the world was not astounded. Though the pictures were decently received, they created no sensation. No one noticed the meaningful initials.

The following year the still-unknown Brotherhood launched a putative student magazine, The Germ , which limped through four editions before closing with unpaid bills. Rossetti (a lifetime avoider of exhibitions) chose the Free again, while the others chose the Royal Academy. Rossetti, true to form again, spiced things up a second time by letting slip what the letters PRB stood for. And it was that which brought sensation.