The Modern Portrait Poem

The Modern Portrait Poem

FROM DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI TO EZRA POUND

FRANCES DICKEY

University of Virginia Press

2012 by the Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

First published 2012

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Dickey, Frances, 1970

The modern portrait poem : from Dante Gabriel Rossetti

to Ezra Pound / Frances Dickey.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 9780813932637 (cloth : acid-free paper)

ISBN 9780813932699 (e-book)

1. Poetry, ModernHistory and criticism. 2. PortraitsHistory.

3. Art, ModernInfluence. I. Title.

PN1069.D53 2012

809.103dc23

2011044937

Contents

Illustrations

Acknowledgments

The poets discussed in the following pages drew from and collaborated with each other to an extent that belies traditional ideas of originality. On a more modest scale, the same is true of this book, built from the contributions of other scholars, shaped by the suggestions and ideas of my teachers, colleagues, and students, and most of all founded on the loving support of my husband, Matthew McGrath, and my sons Thomas and Charles. Without their sacrifices, encouragement, and belief that I would finish, I never could have done so. I dedicate this book to them.

I would like to thank my colleagues at the University of Missouri, especially Timothy Materer, for his encyclopedic knowledge of modern poetry and patient reading of the whole manuscript. In many late night sessions, Alexandra Socarides and Anne Myers also beat and coaxed shapeless writing into argument, vagueness into clarity (but any vagueness that remains is mine). I am grateful to the University of Missouri Research Board, Research Council, and the Center for Arts and Humanities for research leave and funding support. Conversations with members of my 2006 portraiture seminar shaped my initial perceptions of the genre and have fruitfully continued over the years; Peter Monacell and Stefanie Wortman edited and commented on portions of the manuscript; and the students in my 2011 genre seminar helped me work out some final knots as I was finishing.

Special gratitude is due to Jahan Ramazani, who selected my article Parrots Eye: A Portrait by Manet and Two by T. S. Eliot for the Kappel Prize at Twentieth-Century Literature in 2006, a vote of confidence that inspired the writing of this book. Thanks also to the journal for permission to reprint portions of that article here. Christopher Ricks, Eliot scholar extraordinaire, contributed essential guidance and leavening to my project. Members of the T. S. Eliot Society also made this book possible by their generous reception of my papers, perceptive comments and corrections, and enthusiasm for the poetry of St. Louiss native son. I would especially like to thank Anthony Cuda, David Chinitz, Michael Coyle, Benjamin Lockerd, Cyrena Pondrom, and Melanie and Tony Fathman. Although this book is not based on my dissertation, I have continued to draw on what I learned from my advisors, Allen Grossman and Walter Benn Michaels. My friends Dan Gil and Faye Halpern also helpfully commented on early versions of chapters in this book. Advice from anonymous referees on grant proposals and on my manuscript at the University of Virginia Press helped organize the book and make it more readable. Thanks also to editors Cathie Brettschneider, Ellen Satrom, and Mark Mones for their expert guidance.

Finally, I wish to thank family members and friends who assisted in countless ways with the work of caring for my children during six years of research and writing, especially their three grandparents, Barbara Dickey and Fran and Gary McGrath, and my friend Rebecca Senzer, who helped out in New Haven so that I could look at manuscripts. I remember with gratitude Thomas Dickey and Franklin Allen, whose kindness continues to sustain life and work.

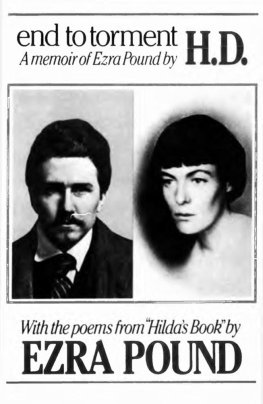

Thanks to the librarians at the Yale Beinecke Rare Book Library for access to the manuscripts of To La Mre Inconnue and Moeurs Contemporaines. Unpublished material by Ezra Pound: Copyright 2012 by Mary de Rachewiltz and the Estate of Omar S. Pound. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corporation. Thanks also to the owners of Charles Demuths A Prince of Court Painters for permission to reproduce this painting, and to the Wyndham Lewis Memorial Trust for permission to reproduce The Dancers.

The Modern Portrait Poem

Introduction

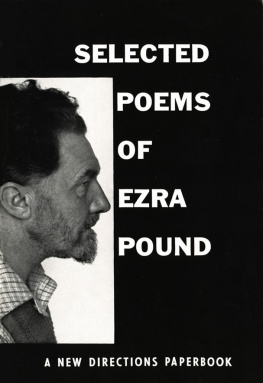

IN 1908, T. S. ELIOT saw a painting by Manet and described it in one of his first poems, On a Portrait. A year and a half later, he began Portrait of a Lady in his rooms at Harvard, finishing it in Paris in November, but keeping it to himself until he met Ezra Pound in London four years later. In the meantime, Pound had written several of his own portraits, including Portrait dune femme (1912), and went on to develop the genre in the sequences Moeurs Contemporaines and Hugh Selwyn Mauberley. Pounds college friend William Carlos Williams wrote a Self-Portrait series in 1914, followed by Portrait of a Woman in Bed, Portrait in Greys, his own Portrait of a Lady, and other poems with similar titles. Back from the war, E. E. Cummings assembled a sequence of portraits in his manuscript Tulips and Chimneys (1922). This flowering of the portrait poem was not a case of mutual influence, for in most cases the poets were drawn to it before they knew each others writing. Yet the appearance of these works at the very moment of modernization in poetry was also not exactly spontaneous or unprecedented: the portrait poem was a familiar nineteenth-century genre. In the 1860s Dante Gabriel Rossetti and members of his circle had transformed the Victorian portrait poem by bringing it into conversation with new techniques in figure painting. In their exchanges they explored the relations between surface and depth, exterior and interior, as aspects of both art and persons. Around 1908 a new generation of American poets began writing under the sign of Aestheticism and adopted its characteristic genre, making the portrait a vessel for similar questions about identity, interiority, and the relationship between images and words.

Why did the portrait appeal to these young poets at the outset of their careers? Calling a poem Portrait in 1912 identified the work with a set In this book I argue that an earlier moment of exchange and collaboration between art and poetry in the Rossetti circle fostered the visual sensibility and interest in issues of portraiture that became central to American Modernist poetry.

In the 1860s, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, James McNeill Whistler, and Algernon Swinburne explored the possibilities of portraiture in a rapid exchange of related works. In a series of paintings of women, Rossetti and Whistler shifted their emphasis from the illusion of depth (both as a visual quality and a trait of the portrait subject) to an aesthetic of surface and pattern. At the same time, Rossetti and Swinburne composed ekphrastic poems about these paintings, poems that called into question the conventions of the Victorian portrait poem. The Rossetti circle thus used the portrait to raise questions that would again preoccupy Modernist poets around 1910. Does the self consist of a soul or interior, and if so, can we know it from appearances? What constitutes a person, if not an inside and an outside? In view of these questions, what should a portrait represent, and how? These questions bespeak uncertainty about what a person is, about the reliability of vision as a guide to knowing others, and about the role of artistic representation. If these questions seem familiar, it is because they are also core concerns of modern poets, who imitated, responded to, and revised Rossettis portraiture. In this book I trace the reception, adaptation, and modulation of the portrait from Rossetti and Swinburne to Ezra Pound, T. S. Eliot, and William Carlos Williams, as well as E. A. Robinson, Edgar Lee Masters, H.D., Amy Lowell, E. E. Cummings, and the authors of the Spectra literary hoax, Arthur Davison Ficke and Witter Bynner. Through the portrait poem, modern poets absorbed and transmitted the literary and visual culture of the nineteenth century in which they learned to write.

Next page