For Kevin

Contents

Introduction

As a World War II child, I was indelibly marked with a sense of American history as a home to heroes. The first books I remember reading are the Ingri and Edgar DAulaire lives of George Washington and Abraham Lincoln; I can still conjure up images of little George in his wig and frock coat, and young Abe studying by candlelight. The glorification of Americas heroic past was part of the World War II propaganda effort. It was easy to contrast the founding fathers of democracy with the founding fathers of Axis dictatorships.

I was patriotic to the core. I knew the hymn of every armed service and had my own victory garden (I remember radishes). My great-uncle John Burke Horne was a sergeant in the Army, where my mother, his niece Lena, sang for GIs. Uncle Burke was already a hero to me because he was engaged to my personal military role model, Lieutenant Harriet Pickens, a Navy Wave, dazzling in her white dress uniform. I had no idea then that Uncle Burke was a sergeant in the segregated Army or that Harriet was the first black Wave; but I knew that I wanted the war to last long enough for me to wear the uniform. Like any other World War II child, I aspired to heroism. I also equated victory with virtue. I had no idea then that there were wartime race riots in northern cities, often over black war workers. And I had no idea that black GIs often sat behind German prisoners of war at United Service Organizations shows, although my mother was banned from the USO for refusing to sing at such an event.

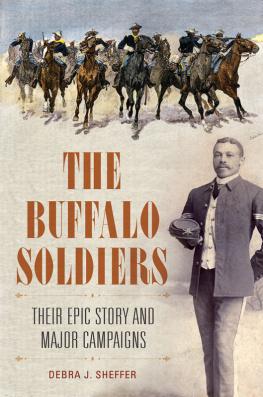

Later on, when I began to research The Hornes, a family history, I found another hero, Burkes much older brother Errol. The oldest of four brothers and a city boy, despite the farm at the end of the street (a token of Brooklyns bucolic roots), Errol was the product of an integrated neighborhood as well as an integrated education. There was no military tradition in the family, but somehow he decided to make a career in the Army, then based in the faraway vastness of the West, home of the 9th and 10th Cavalries and 24th and 25th Infantries: the legendary Buffalo Soldier Regiments.

Always a superb athlete, Errol was taught to ride and shoot by old Indian-fighters at Fort Huachuca, in the Arizona desert. Among the very few nonsegregated activities in the Army, all-unit marksmanship and riding competitions regularly awarded top prizes to blacks. By 1916, handsome twenty-six-year-old Sergeant Horne was at the top of his profession. (In those days, sergeant was the highest rank to which a black soldier could aspire.) But Errol was about to be promoted. My mother always remembered being told that Uncle Errol had chased Pancho Villa into Mexico.

In March 1916, a punitive expedition of some five thousand U.S. Army troops under the command of Brigadier General John J. Pershing crossed the Rio Grande, pursuing Pancho Villa in what was the fourth Mexican Revolution since 1910. Among those seeking the bandit-revolutionary, and revenge for the seven soldiers killed in his raid on Columbus, New Mexico, were members of the black, Texas-based 24th Infantry and 10th Cavalry Regiments: heroes of the Indian Wars, the Spanish-American War of 1898, and the Philippine Insurrection of 18991906. Pershings strategy was to rapidly move three columns southward. Two of the three columns were made up of squadrons of the 10th Cavalry, an indication of Pershings high regard for the black cavalry troops he had led in the Spanish-American War.

In April, sounding familiar bugle calls of help on the way, Major Charles Young and members of the 10th Cavalry raced to the rescue of a large ambushed unit of the white 13th Cavalry at Santa Cruz de Villegas. By God, Young, I could kiss every black face out there, Major Frank Tompkins said to his 10th Cavalry counterpart. If you want, Young said, you may start with me. Villas incursion made national heroes of the 10th and of one of its few black officers, the forty-two-year-old Major Young, the third black graduate of West Point.

War with Mexico was averted only by Americas entry into the First World War. Because of Mexico, Pershing (who owed his nickname, Black Jack, to the color of his troops) was promoted to major general and named chief of the American Expeditionary Forces in France. Major Young, a hero of the Philippine Insurrection as well as of the pursuit of Villa, was promoted to lieutenant colonelbut then declared physically unfit for further combat and retired from active duty. The reason was simple: if Young went to France as a full colonel, he might come back home as a brigadier. And the American military would never countenance a black general. To prove his fitness, Young mounted his cavalry horse, Charlie, for a nonstop Pony Express dash from Wilberforce University in Ohio to the Department of the Army in Washington. The Army was forced to surrender, more or less. Young was promoted to full colonelbut not recalled to active duty until the last week of the war.

While the Mexican campaign meant the end of Charles Youngs career, it was a breakthrough and a new beginning for Sergeant Errol Horne. Junior officers were needed for the new black labor divisions scheduled to be sent to France, and Errol was called to the First World War as a second lieutenant. He got his lieutenants bars and, at almost the same time, married a lovely young woman named Lottie. He took her picture sometime in 1917 before setting off for active duty. His shadow holding the box camera is clearly visible, as Lottie poses in a white middy dress that seems almost translucent in the harsh glare of the desert sunlight.

Within a year, twenty-eight-year-old Lieutenant Horne was dead, a victim of the influenza pandemic that swept the ranks of the American Expeditionary Forces and much of the world in the winter of 1918. Everything possible was done for him, and he was buried with every military honor, but O, it is a deep, deep sorrow, my great-grandmother wrote in a black-bordered note to a cousin. Am here in the country trying to rest mind and body, she said. I have Lottie with me and she is a wreck. It is impossible to know how much of the war Errol actually saw: his records were among those destroyed in the tragic 1973 fire in the U.S. Army archives.

* * *

American history is full of heroes. For a long time, it seemed that none of them were black. Yet there have been black heroes from the beginning; they were simply cut out of the picture. What do heroes do? They fight dragons. And blacks have been fighting the dragons of racism since the country began. One of their most powerful weapons, I learned, was military service. In going to war, black men and women believed they could both better their own lives and make their country true to its own best promise.

I discovered Crispus Attucks, the first black hero of the Revolution, in my World War II childhood when our propaganda effort (in contrast to the Axis powers) celebrated multicultural heroes. For a long time, I assumed that Crispus Attucks was the only black hero of the Revolution. Researching this book I found a world of black heroes, many connected to the most treasured and sacrosanct images of the Revolution. All the heroes of the Revolution, white and black, were founders of our nation.

Midway through the Revolutionary War, some 15 percent of the Continental Army was black. They mix, march, mess and sleep with the Whites, wrote the eighteenth-century historian William Smith of the integrated American ranks. Only half-disapproving, Washington ultimately called his army a mixed multitude. It would be the last mixed multitude for 175 years, until the Korean War.

Next page