Introduction

T he Portuguese, by their discoveries and conquests east of the Red Sea in the sixteenth century, were the people who brought Europe and Asia together in modern times. While they were going East, the Spaniards were going West. In the Spanish conquest of Mexico the clash between the Catholic thought of Europe and the system of ideas which prevailed in Central America was more violent than the clash between European and Asian thought. The Portuguese made little immediate impression on India, but the Spanish way of life quickly prevailed in America. I had found it a subject of great interest to trace the interaction of the cultures of Europe and the Orient. The clash in the opposite direction, when I came to study it, seemed yet more absorbing, because it was concentrated in a single event of an extraordinary kind, the meeting of Corts with Montezuma. The facts of the drama in which these two men were involved are, in general, well established. Prescott, in the nineteenth century, and Madariaga in recent years, have covered the ground in long scholarly books. But what the facts mean remains, and perhaps will always remain, in dispute. For Prescott the hero was Corts, a white adventurer who achieved with a handful of men the conquest of a powerful barbarian kingdom. Madariaga, aware that this was an old-fashioned simplification in view of the extensive information which is becoming available about the ancient and curious civilization of Central America, presented Corts in a more modern historical perspective. He remains, however, the leading figure of the drama.

The present book, hardly as much as a quarter as long as Prescotts or Madariagas, is an attempt to interpret the facts in the light of the latest researches into the Mexican way of thought. My first concern has been to try for a clear and consistent explanation of each situation as it arrives. Without intending disrespect to what is an historical classic, one is obliged to say that Prescott in his The Conquest of Mexico fails to make sense of many of the singular events which he describes. It was, indeed, impossible for any writer to do so in the period when he wrote. Madariaga in his Hemn Corts, acutely conscious that Prescott does not make sense, strives to do so with all the learning at his command. I have struggled to take Madariagas elucidations a little further. In this difficult task I have been greatly helped by advice given me by Mr. C. A. Burland, the eminent student of Central Americas old magical books, whose kindness and generosity are no less noteworthy than his scholarship. As I worked on the sources I came to see Montezuma as an even stranger personage than has generally been supposed. He cannot, as in former books, be given second place. The drama is his as much as Corts. Indeed, of the two protagonists he is the more interesting because he is the more mysterious. To penetrate the mystery of his actions is one of the chief objects of this book.

For those already acquainted with the subject, I should state that I have not used the term Aztec, hitherto employed to denominate the race which ruled Central America at the time of the conquest. The race was called the Mexica in its own language, Nauatl. The Spanish writers contemporary with the conquest use this word in its form as Mexican. Aztec is not found in the Nauatl language. It was coined by Europeans after the conquest and seems to be of questionable validity. The time has come to forget it. The time has also come, I think, to discontinue the term Indians for the original Americans. But that will be more difficult.

The spelling of all the Mexican names and their translations are taken from the index and glossary of Vol. II of the Codex Mendoza as edited by James Cooper Clark.

The authorities I have used are cited in the text, though page references are omitted as being unsuitable for an essay of this kind. The student, however, will have no difficulty in locating them. I am indebted to Mr. Nicholas Egon for helping me with Dr. Selers German translation of Sahagns Nauatl text, to Mr. Cawthra Mulock who lent me a suggestive article on the cosmic aspects of Mexican mythology, and to Dr. Joseph Needham who drew my attention to Jacques Soustrelles La Pense Cosmologique des Anciens Mexicains.

The quotations from authorities are in inverted commas, but in some passages (for instance, Bernal Dazs soliloquy on the old Conquistadors at the end of the book) inverted commas are not used, because the passages are not direct quotations, but rather the summary of the text.

MAURICE COLLIS

{1}

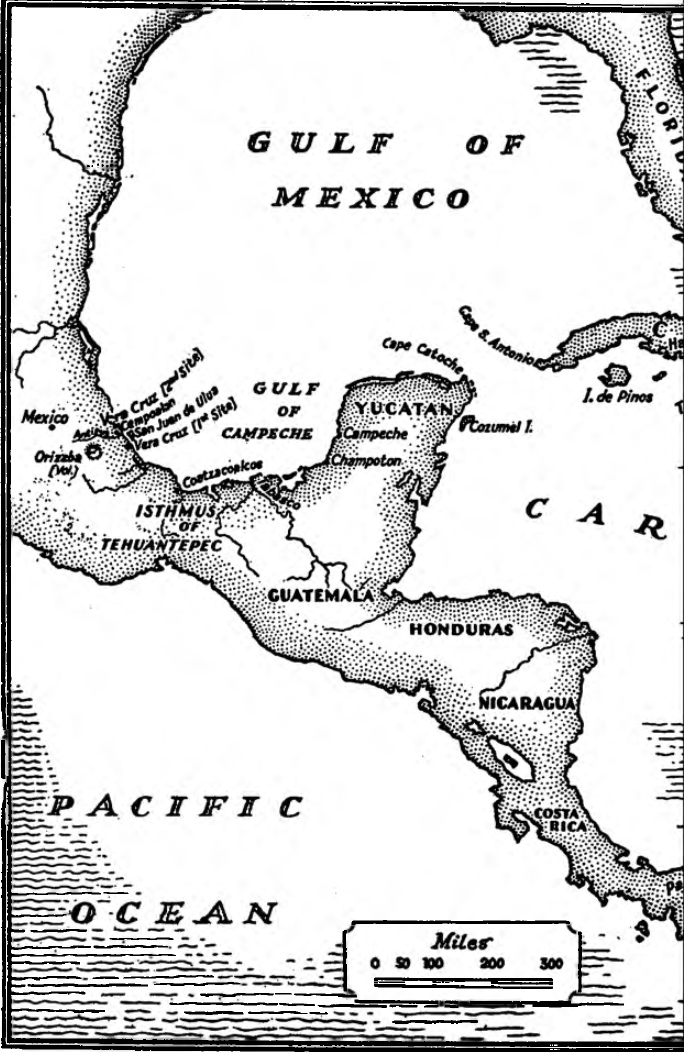

Corts in the West Indies

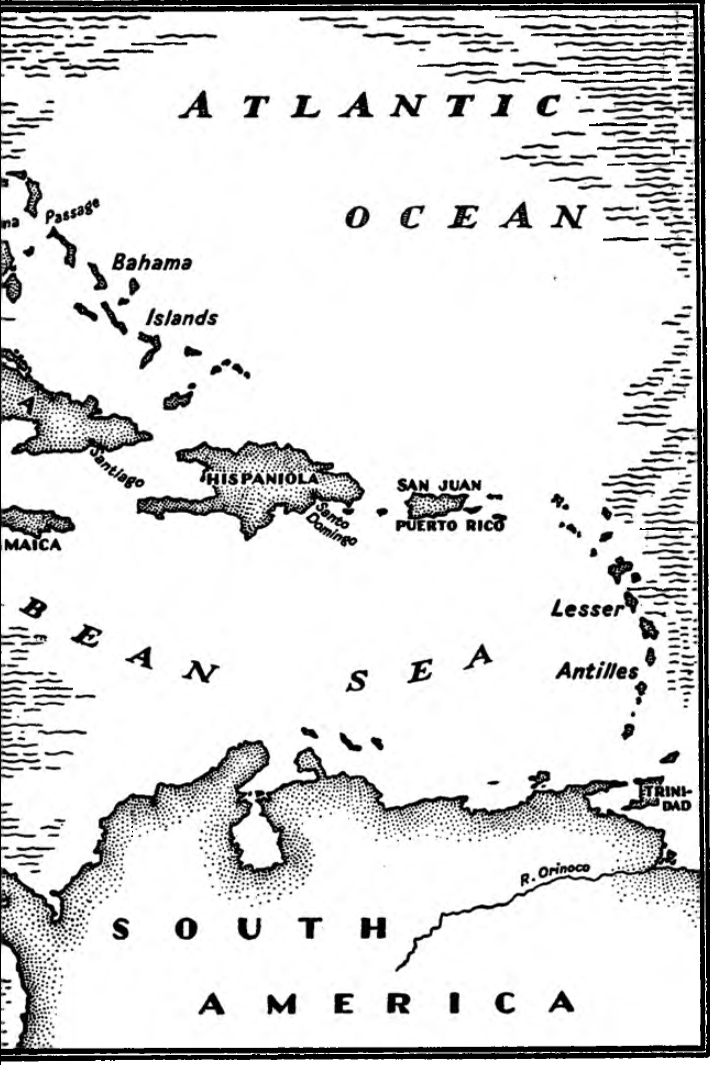

T he Magnificent Lord Cristbal Coln (whom we always call Christopher Columbus) sighted Watling Island in the Bahamas on 11th October 1492. Thence he went on to discover the West Indian islands of Cuba and Hispaniola (Haiti). On his return to Spain in 1493, he informed King Ferdinand that he had reached the outlying parts of eastern Asia, somewhere in the neighbourhood of Japan or China. He did not know that the continent of America lay between what he had discovered and what he thought he had discovered.

The two kingdoms of the Iberian peninsula, Spain and Portugal, were exploring in opposite directions. When Columbus discovered the West Indies, the Portuguese were navigating as far as the Cape of Good Hope in a methodical attempt to reach the East Indies. To avoid disputes in the future the two countries asked the Borgia Pope, Alexander VI, to demarcate their spheres of interest. Taking a pen he drew a line down the middle of the Atlantic and in a Bull called Inter Caetera declared the Portuguese to have exclusive rights to all lands they already possessed or might discover eastward of it and the Spaniards a similar right to what Columbus had discovered in the West Indies and to what subsequently they might come upon beyond those islands.