AUTHORS NOTE

I N 2001 I MOVED TO SEOUL AS A CORRESPONDENT FOR THE Los Angeles Times, covering both Koreas. At the time, it was exceedingly difficult for an American journalist to visit North Korea. Even after I succeeded in getting into the country, I found that reporting was almost impossible. Western journalists were assigned minders whose job it was to make certain that no unauthorized conversations took place and visitors hewed to a carefully selected itinerary of monuments. There was no contact permitted with ordinary citizens. In photographs and on television, North Koreans appeared to be automatons, goose-stepping in formation at military parades or performing gymnastics en masse in homage to the leadership. Staring at the photographs, Id try to discern what was behind those blank faces.

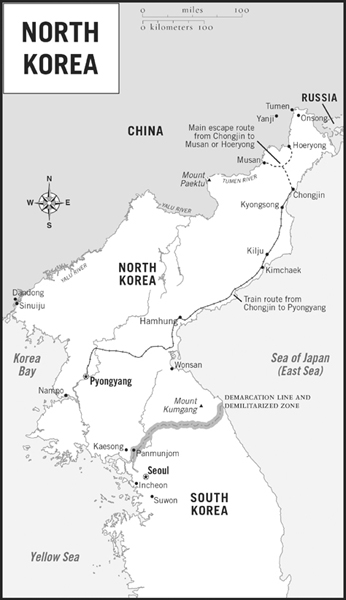

In South Korea, I began to talk to North Koreans who had defected, escaping to South Korea or China, and a picture of real life in the Democratic Peoples Republic of Korea began to emerge. I wrote a series of articles for the Los Angeles Times that focused on former residents of Chongjin, a city located in the northernmost reaches of the country. I believed that I could verify facts more easily if I spoke to numerous people about one place. I wanted that place to be far from the well-manicured sights that the North Korean government shows to foreign visitorseven if it meant I would be writing about a place that was off limits. Chongjin is North Koreas third-largest city and one of the places that were hardest hit by the famine of the mid-1990s. It is also almost entirely closed to foreigners. I had the good fortune to meet many wonderful people from Chongjin who were both articulate and generous with their time. Nothing to Envy grew out of that original series of articles.

This book is based on seven years of conversations with North Koreans. I have altered only some of the names to protect those still living in North Korea. All of the dialogue is drawn from the accounts of one or more people present. I have attempted as best I can to corroborate the stories I was told and to match them with publicly reported events. The descriptions of places that I havent visited personally come from defectors, photographs, and videos. So much about North Korea remains impenetrable that it would be folly to claim Ive gotten everything right. My hope is that one day North Korea will be open and we will be able to judge for ourselves what really happened there.

CHAPTER 1

HOLDING HANDS IN THE DARK

Satellite photo of North and South Korea by night.

I F YOU LOOK AT SATELLITE PHOTOGRAPHS OF THE FAR EAST by night, youll see a large splotch curiously lacking in light. This area of darkness is the Democratic Peoples Republic of Korea.

Next to this mysterious black hole, South Korea, Japan, and now China fairly gleam with prosperity. Even from hundreds of miles above, the billboards, the headlights and streetlights, the neon of the fast-food chains appear as tiny white dots signifying people going about their business as twenty-first-century energy consumers. Then, in the middle of it all, an expanse of blackness nearly as large as England. It is baffling how a nation of 23 million people can appear as vacant as the oceans. North Korea is simply a blank.

North Korea faded to black in the early 1990s. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, which had propped up its old Communist ally with cheap fuel oil, North Koreas creakily inefficient economy collapsed. Power stations rusted into ruin. The lights went out. Hungry people scaled utility poles to pilfer bits of copper wire to swap for food. When the sun drops low in the sky, the landscape fades to gray and the squat little houses are swallowed up by the night. Entire villages vanish into the dusk. Even in parts of the showcase capital of Pyongyang, you can stroll down the middle of a main street at night without being able to see the buildings on either side.

When outsiders stare into the void that is todays North Korea, they think of remote villages of Africa or Southeast Asia where the civilizing hand of electricity has not yet reached. But North Korea is not an undeveloped country; it is a country that has fallen out of the developed world. You can see the evidence of what once was and what has been lost dangling overhead alongside any major North Korean roadthe skeletal wires of the rusted electrical grid that once covered the entire country.

North Koreans beyond middle age remember well when they had more electricity (and for that matter food) than their pro-American cousins in South Korea, and that compounds the indignity of spending their nights sitting in the dark. Back in the 1990s, the United States offered to help North Korea with its energy needs if it gave up its nuclear weapons program. But the deal fell apart after the Bush administration accused the North Koreans of reneging on their promises. North Koreans complain bitterly about the darkness, which they still blame on the U.S. sanctions. They cant read at night. They cant watch television. We have no culture without electricity, a burly North Korean security guard once told me accusingly.

But the dark has advantages of its own. Especially if you are a teenager dating somebody you cant be seen with.

When adults go to bed, sometimes as early as 7:00 P.M. in winter, it is easy enough to slip out of the house. The darkness confers measures of privacy and freedom as hard to come by in North Korea as electricity. Wrapped in a magic cloak of invisibility, you can do what you like without worrying about the prying eyes of parents, neighbors, or secret police.

I met many North Koreans who told me how much they learned to love the darkness, but it was the story of one teenage girl and her boyfriend that impressed me most. She was twelve years old when she met a young man three years older from a neighboring town. Her family was low-ranking in the byzantine system of social controls in place in North Korea. To be seen in public together would damage the boys career prospects as well as her reputation as a virtuous young woman. So their dates consisted entirely of long walks in the dark. There was nothing else to do anyway; by the time they started dating in earnest in the early 1990s, none of the restaurants or cinemas were operating because of the lack of power.

They would meet after dinner. The girl had instructed her boyfriend not to knock on the front door and risk questions from her older sisters, younger brother, or the nosy neighbors. They lived squeezed together in a long, narrow building behind which was a common outhouse shared by a dozen families. The houses were set off from the street by a white wall, just above eye level in height. The boy found a spot behind the wall where nobody would notice him as the light seeped out of the day. The clatter of the neighbors washing the dishes or using the toilet masked the sound of his footsteps. He would wait hours for her, maybe two or three. It didnt matter. The cadence of life is slower in North Korea. Nobody owned a watch.