ALSO BY BARBARA DEMICK

NOTHING TO ENVY

2012 Spiegel & Grau eBook Edition

Copyright 1996, 2012 by Barbara Demick

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Spiegel & Grau, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

S PIEGEL & G RAU and Design is a registered trademark of Random House, Inc.

Originally published in hardcover and in different form in the United States by Andrews McMeel, a Universal Press Syndicate Company, in 1996.

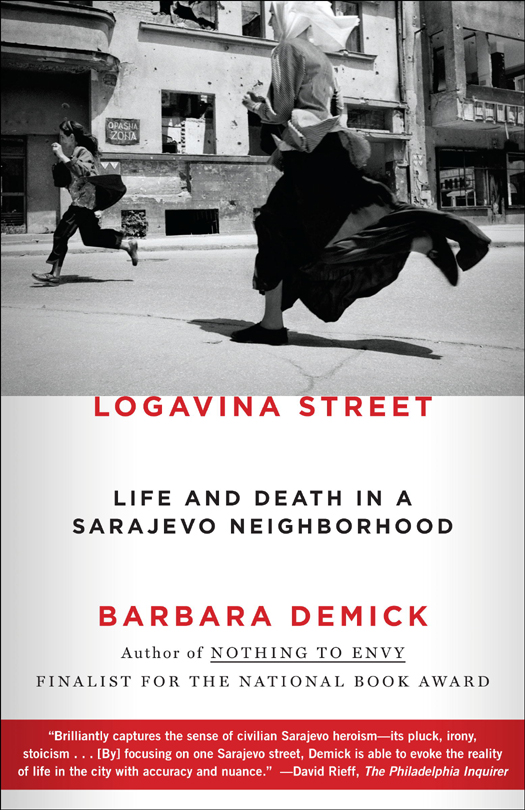

Photographs by John Costello

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Demick, Barbara.

Logavina Street: life and death in a Sarajevo neighborhood / by Barbara Demick.Spiegel & Grau trade pbk. ed.

p. cm.

Originally published in hardcover in the United States by Andrews McMeel in 1996T.p. verso.

eISBN: 978-0-679-64412-5

1. Sarajevo (Bosnia and Hercegovina)HistorySiege, 19921996Personal narratives. 2. Yugoslav War, 19911995Personal narratives, Bosnian. 3. Sarajevo (Bosnia and Hercegovina)Biography. 4. Sarajevo (Bosnia and Hercegovina)Social conditions20th century. 5. NeighborhoodsBosnia and HercegovinaSarajevoHistory20th century. 6. War and societyBosnia and HercegovinaSarajevoHistory20th century. 7. Civilians in warBosnia and HercegovinaSarajevoHistory20th century. 8. Civilian war casualtiesBosnia and HercegovinaSarajevoHistory20th century. 9. Demick, BarbaraTravelBosnia and HercegovinaSarajevo. I. Title.

DR1313.32.S27D46 2012

949.703dc23

2011048307

www.spiegelandgrau.com

v3.1

Dedicated to

Elizabeth Neuffer (19562003)

PREFACE

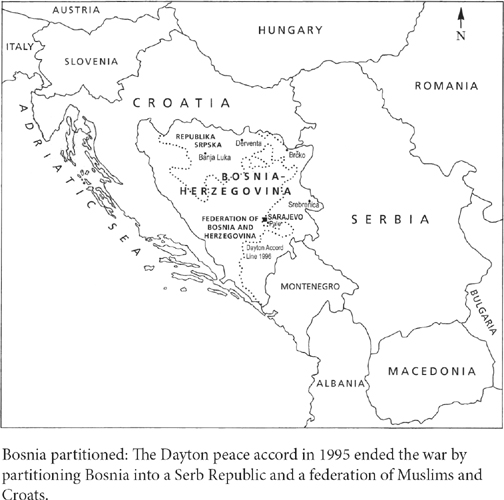

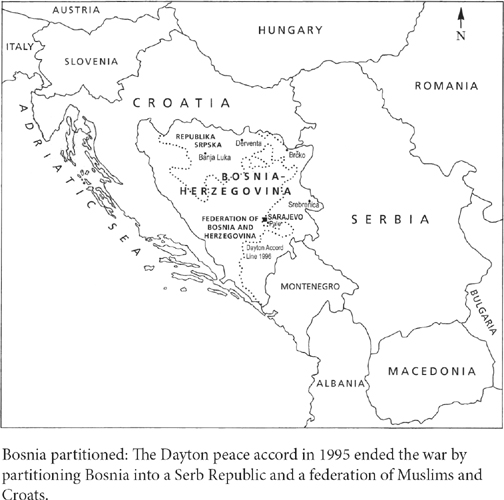

I N 1991, THE YEAR that the Soviet Union broke up, a nationalist revival was sweeping Eastern Europe. It found its most pernicious expression in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, a country patched together in 1943 out of six republics. Slovenia, the richest and most westernized, extricated itself after only a ten-day war. Croatias war was longer and deadlier. The Yugoslav National Army, dominated by Serbs, put up more of a fight to hold on to the boomerang-shaped republic that included most of the Adriatic coastline. The savagery reached its height the following year when Bosnia declared its independence from the country that had been collapsing around it. Bosnia was the most ethnically diverse of the republics, and its leaders proposed that it would be in effect a mini-Yugoslavia of Serbs, Croats, and Muslims living together. Nationalists in the Serb population wanted to remain with Serbia and formed a breakaway republic, the Republika Srpska. With the tacit support of Serbian president Slobodan Miloevi, they commandeered much of the weaponry of the disbanding Yugoslav National Army and launched a campaign to erase the Muslim presence on the lands they claimed for their own. Concentration camps and mass graves returned to Europe for the first time since World War II. The beautiful city of Sarajevo, with its mosques, synagogues, Orthodox and Catholic churches, was besieged for three and a half years, its food and electric supplies cut off, its civilian population relentlessly bombarded.

Given our experiences of the past two decadesthe September 11 attacks, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistanit is hard to imagine how shocked the world was by the brutality in Bosnia.

The early 90s were a time of giddy optimism. A celebratory mood followed the end of the Cold War. The first Persian Gulf War had been waged and won. The Berlin Wall was gone. Liberal democratic values had triumphed, and we thought we could close the door on the evils of the twentieth century. People were talking about peace dividend and new world order. Who would have guessed that the term ethnic cleansing would instead enter the popular lexicon?

In 1993 I accepted an assignment from my newspaper, The Philadelphia Inquirer, to report on Eastern Europe while based in Berlin. My background was in investigative and financial reporting (I had recently covered the issue of campaign finance for the 1992 U.S. presidential race, in which Bill Clinton was elected). My focus in Berlin was supposed to be on the reshaping of the regions economy, postCold War. As for that nasty little war going on in the former Yugoslavia, a colleague assured me, It will be over by the time you get there.

Of course it wasnt. And during my stint in Eastern Europe, I never wrote an economic story. The war in Bosnia subsumed my entire four years in Eastern Europe, and I lived less in Berlin than in Sarajevo.

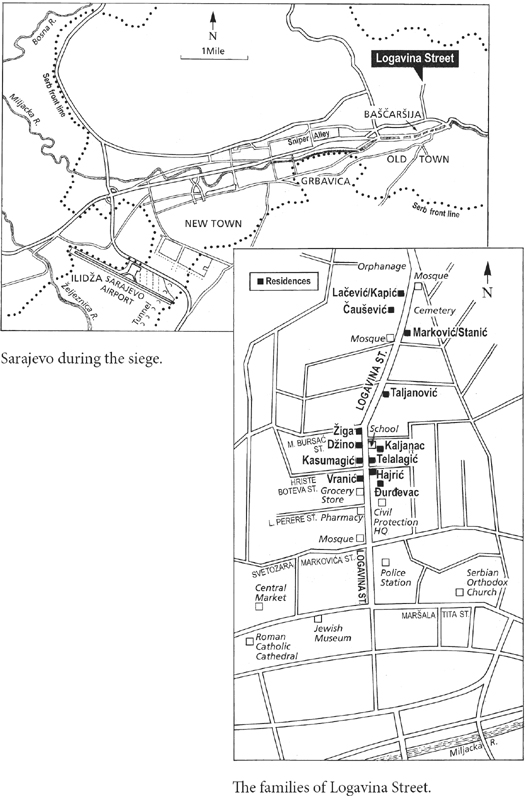

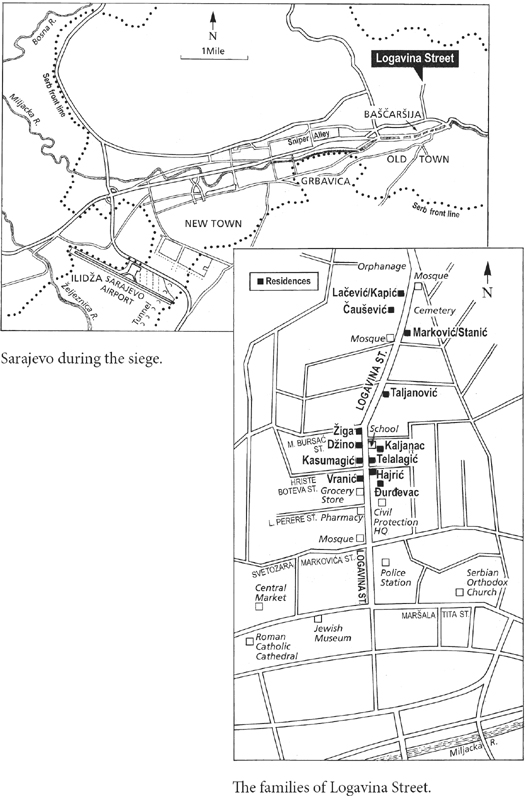

I first came to Sarajevo in January 1994 on a C-130 cargo plane from Split, on the Croatian coast, that was part of the UN airlift bringing aid into the besieged city. When we arrived, we sprinted to the terminal, bags flung over our shoulders, because the airport was under constant fire from Bosnian Serb gunners. We rode downtown in an armored personnel carrier. Like the rest of the press corps, I was staying in the Holiday Inn, its mustard-colored glass faade on the south side blown away by mortar fire from the Serb lines just across the river, less than a mile away.

Luckily, my room faced north. But there were bullet holes and shrapnel in the wall, around which somebody had drawn circles on the wallpaper and written down the dates. It was not an encouraging sign.

A whole generation of war correspondents cut their teeth covering Bosnia, watching from the ground up as a civilian population was bombed and besieged. It was so difficult to get in and out of Sarajevo that a huge press corps simply moved in and became ourselves part of the story. I experienced the siege with the Sarajevans. True, we had electricity, some food, and occasional running water and many of us drove around in armored cars, but we were as vulnerable as anybody to the constant mortar fire. In this environment, the line between journalist and subject blurred.

From the outside, the conflict seemed very complicatedancient Balkan hatreds, geopolitical fault lines, and all that stuffbut when you were actually there, it was simple. Civilians were trapped inside the city; people with guns were shooting at themand us. The Sarajevans were impressive. Well into the war, well past the point that brutality should have engendered hatred, when idealism should have been shattered, most Sarajevans still believed they could preserve a multicultural space in their city.

Sarajevo became a cause and a cri de guerre. In the Western world, its very namelike Darfur or Dunkirkelicited knowing and downcast looks. Luciano Pavarotti organized humanitarian concerts; U2s Bono composed the song Miss Sarajevo and visited at the end of the war. The writer Susan Sontag visited Sarajevo when the war was at its height and directed a production of Waiting for Godot. She later compared Sarajevo to the Spanish Civil War, calling both emblematic events that seemed to sum up the principal opposing forces of ones time.

When I arrived, an empathy fatigueas they called it in the humanitarian aid businesshad settled over Bosnia. Readers were numbed to the suffering of a people whose names they couldnt pronounce in a place theyd never been. To bring home the reality of the war, my editors suggested that, with staff photographer John Costello, I pick a street in Sarajevo and profile the people living there, describing their lives during the war.