Miscellany

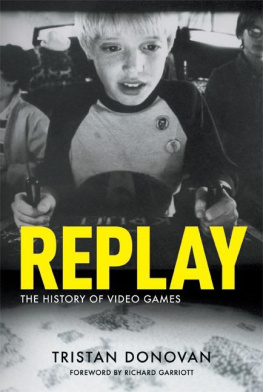

Cover

Dedication

To Jay, Mum, Dad and Jade

Acknowledgements

This book would not have been possible without the support and help of many other people. My partner Jay Priest tops the thank you list for his design work on the book, support in getting the whole project off the ground, sound advice, help with the research and business aspects, and above all for his patience and unfailing support over the year-and-a-half it took me to write it.

Keith Grimes and David McCulloughs insights and suggestions were incredibly helpful, as was their willingness to help me sift through dozens and dozens of good (and many not so good) games when putting together the books game guide. Also a special thanks to Keith for making the iBook version possible.

Tom Homewood gets a big thank you for his work on the cover design and his advice on typeography as does my crack proofreading team of Ruth Smith, Cathy Wallace and Rachael Wood, who were willing to make their way through a book on a subject they knew nothing about in meticulous detail. Cathy Wallace gets an extra mention for her tweets.

My Japanese translator Klara Ellefson went beyond the call of duty by providing me with numerous useful insights in Japanese culture and through her willingness to help track down several of the Japanese developers I interviewed.

Thanks also go to: Cathy Campos of Panache PR for her patience with the delays to the books completion and her PR work, Jess McAree for the legal pointers, and Jon Savage for inspiration (although he doesnt know it).

Lastly, and by no means least, Ill like to thank the hundreds of game industry veterans, PRs and agents who I contacted while researching this book for the time they took in answering my many questions, helping me track down the information I needed and for digging out photos or images for the book. A special thanks goes to Ralph Baer, Dona Bailey, Dave Nutting, Cynthia Franco (of the DeGolyer Library at Southern Methodist University, Dallas), Richard Garriott, Eugene Jarvis, Ed Logg and Philip Oliver who all went the extra mile.

Space race: Spacewar! co-creators Dan Edwards (left) and Peter Samson engage in intergalactic warfare on a PDP-1 circa 1962. Courtesy of the Computer History Museum

1. Hey! Lets Play Games!

The world changed forever on the morning of the 17th July 1945. At 5.29am the first atomic bomb exploded at the Alamogordo Bombing Range in the Jornada del Muerto desert, New Mexico. The blast swelled into an intimidating mushroom cloud that rose 7.5 kilometres into the sky and ripped out a 3-metre-deep crater lined with irradiated glass formed from melted sand. The explosion marked the consummation of the top-secret Manhattan Project that had tasked some of the Allies best scientists and engineers with building the ultimate weapon - a weapon that would end the Second World War.

Within weeks of the Alamogordo test, atomic bombs had levelled the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The bombs killed thousands instantly and left many more to die slowly from radiation poisoning. Five days after the destruction of Nagasaki on the 9th August 1945, the Japanese government surrendered. The Second World War was over. The world the war left behind was polarised between the communist east, led by the USSR, and the US-led free-market democracies of the west. The relationship between the wartime allies of the USA and USSR soon unravelled resulting in the Cold War, a 40-year standoff that would repeatedly take the world to the brink of nuclear war.

But the Cold War was more than just a military conflict. It was a struggle between two incompatible visions of the future and would be fought not just in diplomacy and warfare but also in economic development, propaganda, espionage and technological progress. And it was in the technological arms race of the Cold War that the video game would be conceived.

* * *

On the 14th February 1946, exactly six months after Japans surrender, the University of Pennsylvania switched on the first programmable computer: the Electronic Numeric Integrator and Calculator, or ENIAC for short. The state-of-the-art computer took three years to build, cost $500,000 of US military funding and was created to calculate artillery-firing tables for the army. It was a colossus of a machine, weighing 30 tonnes and requiring 63 square metres of floor space. Its innards contained more than 1,500 mechanical relays and 17,000 vacuum tubes the automated switches that allowed the ENIAC to carry out instructions and make calculations. Since it had no screen or keyboard, instructions were fed in using punch cards. The ENIAC would reply by printing punch cards of its own. These then had to be fed into an IBM accounting machine to be translated into anything of meaning. The press heralded the ENIAC as a giant brain.

It was an apt description given that many computer scientists dreamed of creating an artificial intelligence. Foremost among these computer scientists were the British mathematician Alan Turing and the American computing expert Claude Shannon. The pair had worked together during the war decrypting the secret codes used by German U-boats. The pairs ideas and theories would form the foundations of modern computing. They saw artificial intelligence as the ultimate aim of computer research and both agreed that getting a computer to defeat a human at Chess would be an important step towards realising that dream.

The board games appeal as a tool for artificial intelligence research was simple. While rules of Chess are straightforward, the variety of possible moves and situations meant that even if a computer could play a million games of Chess every second it would take 10 years for it to play every possible version of the game. As a result any computer that could defeat an expert human player at Chess would need to be able to react to and anticipate the moves of that person in an intelligent way. As Shannon put it in his 1950 paper Programming a Computer for Playing Chess: Although perhaps of no practical importance, the question [of computer Chess] is of theoretical interest, and it is hoped that a satisfactory solution of this problem will act as a wedge in attacking other problems of a similar nature and of greater significance.

In 1947, Turing became the first person to write a computer Chess program. However, Turings code was so advanced none of the primitive computers that existed at the time could run it. Eventually in 1952, Turing resorted to testing his Chess game by playing a match with a colleague where he pretended to be the computer. After hours of painstakingly mimicking his computer code, Turing lost to his colleague. He would never get the opportunity to implement his ideas for computer Chess on a computer. The same year that he tested his program with his colleague, he was arrested and convicted of homosexuality. Two years later, having been shunned by the scientific establishment because of his sexuality, he committed suicide by eating an apple laced with cyanide.

While Turing never got to make his Chess program, computer scientists such as Shannon and Alex Bernstein would spend much of the 1950s investigating artificial intelligence by making computers play games. While Chess remained the ultimate test, others brought simpler games to life.

In 1951 the UKs Labour government launched the Festival of Britain, a sprawling year-long national event that it hoped would instil a sense of hope in a population reeling from the aftermath of the Second World War. With UK cities, particularly London, still marred by ruins and bomb craters, the government hoped its celebration of art, science and culture would persuade the population that a better future was on the horizon. Herbert Morrison, the deputy prime minister who oversaw the festivals creation, said the celebrations would be a tonic for the nation. Keen to be involved in the celebrations, the British computer company Ferranti promised the government it would contribute to the festivals Exhibition of Science in South Kensington, London. But by late 1950, with the festival just weeks away, Ferranti still lacked an exhibit. John Bennett, an Australian employee of the firm, came to the rescue.