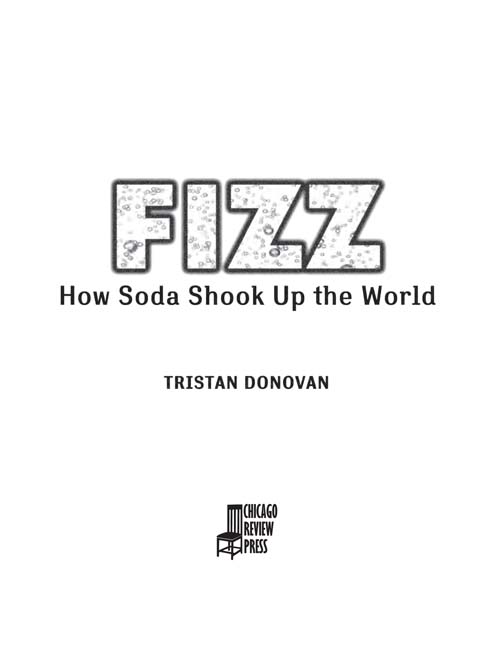

Copyright 2014 by Tristan Donovan

All rights reserved

Published by Chicago Review Press Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 978-1-61374-722-3

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Donovan, Tristan.

Fizz : how soda shook up the world / Tristan Donovan.

pages cm

Summary: This social, cultural, and culinary history charts sodas remarkable, world-changing journey from awe-inspiring natural mystery to ubiquity. Off-the-wall and off beat stories abound, including how quack medicine peddlers spawned some of the worlds biggest brands, how fizzy pop cashed in on Prohibition, how soda helped presidents reach the White House, and even how Pepsi influenced Apples marketing of the iPod. This history of carbonated drinks follows a seemingly simple everyday refreshment as it zinged and pinged over societys taste buds and, in doing so, changed the world Provided by publisher.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61374-722-3 (pbk.)

1. Soft drinksHistory. 2. Carbonated beveragesHistory. I. Title.

TP630.D66 2013

663.62dc23

2013023222

Cover design: Rebecca Lown

Interior design: Jonathan Hahn

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

To J AY

Contents

Index

INTRODUCTION

To the Stars

It was 1984, the height of the Cola War. Pepsi was riding high on the back of the Pepsi Challenge and an endorsement from Michael Jackson, the worlds biggest star. After more than 60 years of trying to beat Coca-Cola, victory was in sight. But the Atlanta soda giant still had a trick up its sleeve to use against its fast-growing Yankee rival: it would take soda into outer space.

Coca-Cola announced to the world that NASA would take its world-famous cola into orbit when the Challenger space shuttle blasted off from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida in July 1985. As more people explore outer space, it was our judgment that it would be a darn shame if people on these long voyages wouldnt have the opportunity to have a moment of refreshment with Coca-Cola, Coke president Don Keough informed USA Today. After all, he could have added, when youve conquered the world, the only direction is up.

Coca-Cola spent a fortune on its space mission, assigning a team of its finest engineers to build a unique soda can capable of dispensing its fizzy nectar to astronauts as they floated in zero gravity. It had taken months to develop and been tested to destruction on high-altitude flights aboard NASAs Vomit Comet, the Boeing KC-135 that the space agency would fly on a parabolic flight path so astronauts could train in a near weightless environment.

The tough steel can featured an adhesive fastener strip so that it could be attached to the spacecraft walls to stop it from floating around. It had a special paint that would not melt in intense heat or flake in extreme cold (in which case it could float off and damage the shuttles circuits). There was a safety lock to stop the liquid from escaping and a spout, activated by a plunger, from which Coca-Cola could be squirted down the throats of space travelers.

At the offices of Pepsi in Purchase, New York, the news that its archrival was to be first into space came as a shock. Bob McGarrah, the equipment development manager at Pepsi when Coca-Cola made its announcement, remembers the reaction: What! Cokes going to space and were not? There might not have been moon bases or Martians out there to buy their fizzy drinks but this was the Cola War and the contest to be crowned soda king was on a knife edge. Pepsi couldnt let Coca-Cola be the first into space. No way. If Coke was going where no soda had gone before, Pepsi was coming too.

Roger Enrico, the president of Pepsi-Cola, ordered his staff to gatecrash Cokes orbital party. Pepsi got in touch with NASA and pointed out to the agency that PepsiCo is strongly identified with the Republican Party and the support of President Reagan and his administration. In short, put us on that shuttle or expect trouble in Washington. What could NASA say except OK?

Having gotten their ticket on the same shuttle flight as Coca-Cola, Pepsi now needed a space can of its own that could pass NASAs rigorous tests. Pepsi assembled its best engineers and told them to make a space can. Fast. One of those on the team was McGarrah: In something like 14 weeks, a really compressed period of time, we had to come up with a package that could go up in a spaceship. Everything thats going to go onto that spaceship has to be tested for things like flammability, ability to withstand a vacuum, and on and on and on. You have to create the product and go through this elaborate testing process out in New Mexico to get approval.

Working out of Pepsis research facility in Valhalla, New York, and with support from spray technology specialists Enviro-Spray, the team raced against the clock to build the kind of space-worthy can that Coca-Cola had spent months developing. One of the team, Scott Gillesby, was the main courier to the testing facility and he would fly back and forth to the testing grounds in New Mexico, McGarrah recalls. He was literally in the air more than he was on the ground; flying out to the test site and back. He had to keep coming back and forth because a lot of the time the can failed.

After several weeks of ferrying prototypes back and forth, Pepsi had their can. Essentially a repurposed aerosol canister, Pepsis steel space can contained small plastic pouches that would mix citric acid and sodium bicarbonate when the spray nozzle was pressed down. The acid and baking soda would react to produce carbon dioxide gas that would cause the pouches to expand, increasing the pressure inside the can and forcing the cola out through the nozzle. On July 8, 1985, with just four days to go before takeoff, NASA gave Pepsi permission to fly. Cokes hopes of being the first soda in space were over. As takeoff approached, the seven astronauts found themselves besieged with questions from journalists wanting the scoop on the Cola Space War. Were not up there to run a taste test between the two, exasperated astronaut Colonel Gordon Fullerton told reporters.

The orbital Pepsi Challenge didnt take off quite as planned. At T minus 3 seconds the shuttle launch was canceled and delayed until July 29 when, finally, the worlds favorite sodas made the journey into space. Back on Earth, Pepsi marked the day with newspaper ads declaring the venture one giant sip for mankind. Once in space the astronauts tested out the cans, blowing wobbly spherical globules of zero-gravity cola around the ship before gulping them down. And when they returned to Earth the assembled press couldnt wait to find out who had won the outer space taste test. Neither, replied the astronauts. The shuttle didnt have a refrigerator, the crew explained, and warm soda just doesnt cut it.

Even worse were the zero-gravity burps from drinking carbonated drinks in space. On Earth, thats not such a big deal, but in microgravity its just gross, Vickie Kloeris, the food systems manager at NASA, reported on the space agencys website in 2001. Because there is no gravity, the contents of your stomach float and tend to stay at the top of your stomach, under the rib cage and close to the valve at the top of your stomach. Because this valve isnt a complete closure (just a muscle that works with gravity), if you burp, it becomes a wet burp from the contents in your stomach. Not that Pepsi cared. Was Cokes can better? Probably, says McGarrah. But Coke was there and we were there too.

Next page