Graham Keevill - Monastic Archaeology

Here you can read online Graham Keevill - Monastic Archaeology full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2017, publisher: Oxbow Books, genre: History / Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Monastic Archaeology

- Author:

- Publisher:Oxbow Books

- Genre:

- Year:2017

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Monastic Archaeology: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Monastic Archaeology" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Monastic Archaeology — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Monastic Archaeology" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Monastic Archaeology

Papers on the Study of Medieval Monasteries

Papers on the Study of Medieval Monasteries

Edited by

Graham Keevill, Mick Aston and Teresa Hall

First published in the United Kingdom in 2001. Reprinted in 2017 by

OXBOW BOOKS

The Old Music Hall, 106108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JE

and in the United States by

OXBOW BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Road, Havertown, PA 19083

Oxbow Books and the individual authors 2001

Paperback Edition: ISBN 978-1-78570-567-0

Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-78570-568-7

Mobi Edition: ISBN 978-1-78570-569-4

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the publisher in writing.

For a complete list of Oxbow titles, please contact:

UNITED KINKUDOM

Oxbow Books

Telephone (01865) 241249, Fax (01865) 794449

Email: oxbow@oxbowbooks.com

www.oxbowbooks.com

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Oxbow Books

Telephone (800) 791-9354, Fax (610) 853-9146

Email: queries@casemateacademic.com

www.casemateacademic.com/oxbow

Oxbow Books is part of the Casemate Group

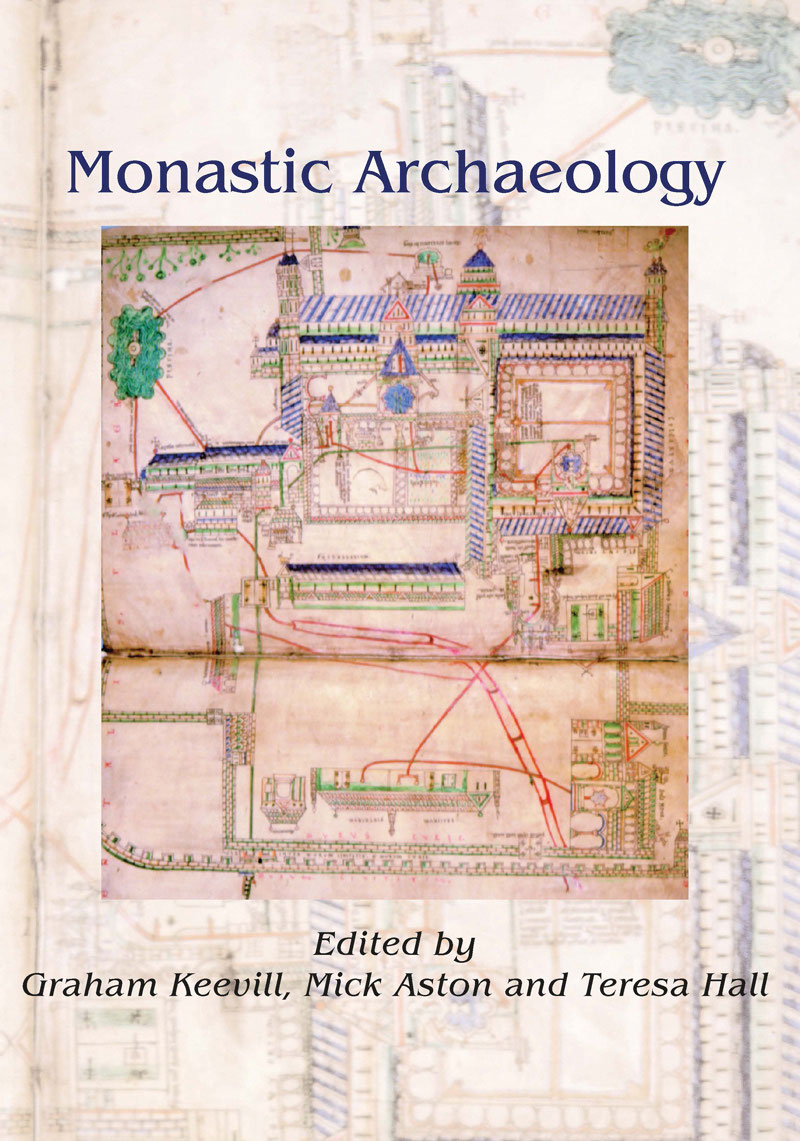

Cover illustration: Trinity MS R.17.1 ff. 2845: Christ Church waterworks drawing

(reproduced by courtesy of the Master and Fellows of Trinity College Cambridge)

The pioneering monastic studies of the late 19th century through to the 1930s perhaps inevitably placed an extremely strong emphasis on the elucidation of ground plans. Information on plan development was also desirable where possible (though interpretations made then are by no means unchallengeable because of the partial nature of the studies; see Coppack, this volume). The best analyses were often based on detailed site surveys allied to extensive documentary research, and some of the extraordinary ground plans (often covering very large surface areas in difficult terrain) stand as lasting testaments to the work of their producers. Sites were studied systematically, and the detailed descriptive reports which appeared virtually annually in the likes of Archaeologia, the Antiquaries Journal and the Archaeological Journal (to say nothing of county periodicals) graphically demonstrate the pioneering zeal and industry of St John Hope, Norman, Brakspear, Clapham, Peers and others. Nevertheless there are few of these surveys which can be taken entirely on trust today, especially where further work has since taken place.

It is not necessarily surprising that most of the surveyors began with a general notion of how monastic plans should look. There were, after all, Catholic monasteries in Britain and Europe to provide a living template, along with post-Dissolution surveys, descriptions and illustrations of many medieval houses. There were also a number of medieval depictions of monastic houses and their precincts to provide a contemporary witness (most notably the famous St Gall template of the 9th century, and the equally well-known late 12thcentury plans of Christ Church Canterbury). The basic requirements of church and cloister with buildings ranged around them were fairly readily understood, but the best early surveys recognised that this was not a blueprint that all sites would automatically conform to. The influence of local topography on the location of the cloister to the south or north of the church was easily recognisable, and the importance of water supplies was also clear. Detailed studies could take this further; at Worcester, for instance, the unusual location of the dorter and reredorter on the west side of the cloister was recognised as a pragmatic use of the location: the river Severn ran along this side of the abbey precinct (Brakspear 1916). An important series of papers also sought to examine the influence of different orders on the architecture and layout of monasteries (eg Clapham 1923; Graham and Clapham 1926), or specific aspects of monastic sites such as water supply (Micklethwaite 1893; Norman 1899; St John Hope 1902; Norman and Mann 1909), while others examined sites on a regional basis (eg Brakspear 1928).

Inevitably, however, the strength of emphasis on the plan tended to restrict the degree of attention to detail around and within the monastic buildings. Furthermore attention was so strongly focused on the church and cloister that the service ranges of the outer court and on occasion even such important inner areas as the infirmary cloister were often overlooked. There are exceptions, of course, such as St John Hopes survey of Hulne (St John Hope 1890), and Brakspear in particular was ahead of his time in this as in other areas of his work. The general attitude was clear, however, and continued largely unaltered into the 1950s, when the recognition of medieval archaeology brought with it a greater sensitivity to the overall monastic environment. Nevertheless a conscious and general shift of emphasis away from church and cloister towards the wider monastic landscape had to wait until much more recent times (see, for instance, virtually all of the papers in Gilchrist and Mytum 1989). The change was codified in the Society for Medieval Archaeologys submission of a framework of research priorities (SMA 1987, section I(c)ii) to English Heritage. Curiously the eventual English Heritage report (EH 1991) scarcely mentioned any aspect of monastic archaeology in its overview of priorities for the 1990s.

Ironically this wider approach to abbeys, though entirely justified in its own right, has deliberately drawn attention away from the church and cloister, the indisputable heart of monastic life. Relatively little attention has been paid to the spiritual and religious aspects of monasticism, perhaps in the belief that early studies of abbeys had already paid due heed to such topics. This would be erroneous, because most early work was aimed at elucidating the architectural development of the churches and determining the layout of the cloisters. All too often there was little (if any) thought of an archaeology of context, whether ceremonial or functional. Recent work at sites such as Bordesley Abbey (Hirst et al 1983), Norton Priory (Greene 1989), Sandwell Priory (Hodder 1991), the Coventry Charterhouse (Soden 1995 and this volume) and Hulton Abbey (Klemperer this volume) has shown the potential for archaeological study of ceremonial matters. Fergusson and Harrisons magisterial examination (1999) of Rievaulx Abbey, that great Yorkshire monument to the Cistercian movement, perhaps shows us the true potential of placing religion at the core of such studies. The archaeology of ritual need not stop at prehistoric sites, and this should be an essential element of monastic studies. We should be examining plans critically rather than relying on notions of what is typical.

All of the above was relevant to my own work during the early 1990s, especially at Eynsham Abbey in Oxfordshire (this volume) where I was in charge of a major archaeological project on a Benedictine house with late Saxon origins. There were many opportunities to share information and ideas with colleagues, most notably at the Medieval Europe 1992 conference in York. The idea for a conference dedicated to monastic archaeology grew out of such exchanges and the realisation that there was a great deal of new work being done which deserved a wider audience. This was true both of individual sites or projects and of more general thematic programmes. There was, of course, ample precedent for holding such reviews of work in progress, notably the conferences on rural and urban monasteries the proceedings of which were published in Gilchrist and Mytum 1989 and 1993 respectively. An approach to Oxford Universitys Department of Continuing Education (OUDCE) late in 1993 to see whether they would be interested in hosting such a conference at Rewley House met with an enthusiastic response. A weekend towards the end of 1994 was duly booked. The task of preparing a draft list of speakers and topics was an interesting one in its own right, the difficulty being to keep the numbers of possible contributions down to a manageable number from OUDCEs point of view. It was gratifying to find that all of the speakers I had chosen were both interested in the idea and willing to contribute; just as remarkably they were all available on the weekend in question. The programme, therefore, came together very quickly and included such luminaries of modern archaeology as Mick Aston, Paul Bennett, Martin Biddle, James Bond, Glyn Coppack, Patrick Greene and Terryl Kinder along with a few names (including my own) which would doubtless have been less familiar to the typical mix of professional colleagues and well-informed amateurs (in the best possible sense of the word) which typifies conferences at Rewley House. The conference itself was immensely enjoyable, even for me given my duties as organiser and host on OUDCEs behalf.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Monastic Archaeology»

Look at similar books to Monastic Archaeology. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Monastic Archaeology and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.