RETRO CLASSICS

is a collection of facsimile reproductions

of popular titles from the 1980s and 1990s

National Trust Histories: The Lake District

was first published in 1984

by William Collins & Co Ltd.

Re-issued in 2015 as a Retro Classic

by G2 Rights

in association with Lennard Publishing

Windmill Cottage

Mackerye End

Harpenden

Hertfordshire

AL5 5DR

Copyright 1984 Chris Barringer and Lennard Books Ltd

ISBN 978-1-78281-148-0

Editor: Michael Leitch

Designed by David Pocknells Company Ltd

Printed and bound by Lightning Source

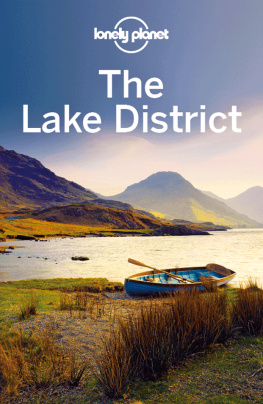

This book is a facsimile reproduction of The Lake District

as it was originally published in 1984.

No attempt has been made to alter any of the wording

with the benefit of hindsight, or to update the book in any way.

C ONTENTS

Character of the region;

Stone Age communities and their domestic remains;

Hadrians Wall and the west coast forts.

The Celtic North-West;

Farming the fells infield and outfield;

Industrial growth;

E DITORS INTRODUCTION

Whenever I visit the Lake District in spring, autumn or winter I am always convinced that there cannot be a more beautiful place in all the world. A glance at the atlas tells us that this is a relatively small and compact area, with the Lake District core of Cumbria covering not that much more ground than the built-up area of London.

The atlas also tells us that the main three-thousand-footer peaks of the region are mere pimples in comparison to the Alps, let alone to the Himalayas. But atlases cannot tell us about the character and ethos of the area, and the Lake District has an aura of bigness which defies the cartographical facts. The lakes seem broader, the grey summits loftier and the crags more defiantly vertical than they really are. The deceptions do not end here, and most visitors probably imagine that in these rugged, largely unspoilt and sometimes almost brutal landscapes one is meeting a natural wilderness. Yet in fact the scenery of the Lake District is emphatically man-made. Were it not for the efforts of man the farmer, active here for at least six thousand years, the fells would still be blanketed in pine, hazel and oak. Today, when so many lovely English landscapes have been heedlessly destroyed by modern agriculture, the tough and sometimes impoverished hill farmers are still helping to maintain the lovely scenery of fell pasture, moor and walls which are the essence of the regions charm.

The Lake District was, until the nineteenth century, a remote, neglected and inaccessible part of England. Before the arrival of good communications and tourism it had been home to successive generations of very hardy people: prehistoric peasant farmers, the defenders of small Roman garrisons, Norse and Saxon settlers, monastic tenants and, after the Dissolution of the Monasteries, the doughty farming families of yeomen or statesmen and communities of miners and quarry workers. Each group has left its powerful imprint on the landscape and there is an exceptional legacy of prehistoric and Roman monuments, interesting medieval castles and monastic buildings and a wealth of post-medieval vernacular buildings in stone, as well as plenty of relics to attract the industrial archaeology enthusiast.

It is fitting that the Lake District should be the subject of one of the first volumes in this series of National Trust regional histories, since the Trust manages so many properties in the region and has done so much to conserve its beauty. There are scores of books which delight in the loveliness of the Lake District, but very few which tell the visitor in uncomplicated terms about the creation of the landscape. There are also very few scholars who understand this story as well as Chris Barringer does. He was educated at Ilkley in Yorkshire and at St Johns College, Cambridge. Between 1954 and 1965 he was Senior Geography Master at Lancaster Royal Grammar School and, working on the threshold of the Lake District, he could explore every facet of the lake and fell country and develop an understanding of the history of its peripheral towns. This close acquaintance with the region has been regularly renewed since he became Resident Tutor in Norfolk for the University of Cambridge Board of Extra-Mural Studies. Chris Barringers previous works include a more detailed guide to the geography of the Lake District and a fine landscape history of the Yorkshire Dales.

Richard Muir

Great Shelford, 1983

T HE SHAPING OF CUMBRIA

Cumbria is one of the most clearly defined areas of England. It stretches from Morecambe Bay to the Solway Firth and from the Irish Sea to the valleys of the Lune and Eden Rivers. Not only is it a clear-cut geographical area, it is also unique in English landscapes for its combination of lakes and mountains. Local government reforms in 1974 recognized this unity of the Lake counties in renaming Cumberland, Westmorland and parts of Lancashire and the West Riding of Yorkshire under the umbrella name of Cumbria. It is sad to have lost Cumberland and Westmorland as names, and the attractive-sounding Lancashire across the sands, but Cumbria has a presence of its own.

Our story begins long before the counties appeared and runs through to modern times and the creation of Englands busiest National Park. Other sections discuss the stories of the Lake poets, the Lake artists and writers, and the growth of the Lakes as a favourite holiday area. These themes are, of course, closely related and one may well ask why such a small part of England has come to be so well-known. The typical English scene, perhaps based on perceptions of Stratford-upon-Avon and the Cotswolds, is often portrayed as one of the slow-flowing stream, of thatched cottages grouped near a timeless church and very probably round a village green. The Lake District, the core of Cumbria, has none of these: its streams roar, its cottages are slate-roofed, and its churches, other than those few in market towns, date largely from the nineteenth century.

Perhaps it is in part this very differentness that attracts the traveller. The concept of the Grand Tour, born in the eighteenth century, and later the Gothic Revival movement in architecture, both stimulated educated people to take an interest in new and unusual places. Wordsworth was born in the Lakes and returned to them and so, through him, many more literary and artistic figures were introduced to the region. Painters looking for the Picturesque turned Lakeland vistas into Wagnerian backdrops: Turner, Towne and Harden presented these new scenes for the delectation of new connoisseurs. The railways and the Lakes steamers allowed the nouveaux riches of Liverpool, Manchester and Tyneside to buy up the Lakeside estates on Windermere and around Keswick.

Since then, the Lake District has held its own with the cut-price, jet-borne search for the sun. The YHA, school trips, Outward Bound projects, the cult of Peter Rabbit, television films on wildlife and rock climbers, and Ken Russells version of Wordsworth striding into the mist, have all drawn new groups of visitors to the Lakes. Meanwhile, the M6 has made it possible for holiday-season motorists to reach Ambleside and Keswick in ever-greater numbers their queues unfortunately matching those which extend out of nearby traditional resorts such as Blackpool and New Brighton. In fact, so successful has the Lake District become as a resort area that its administrators now try to disperse ramblers more evenly and discourage motorists from all seeking to park their cars at the same viewpoint. Perhaps this book can help further those aims by leading walkers and motorists to look beyond the honey pots and discover the host of lesser-known sites when they visit the region, and so enjoy it more fully.

Next page