For all my Cornish cousins

Willow Books

William Collins & Co Ltd

London Glasgow Sydney Auckland

Toronto Johannesburg

Ravensdale, J R

Cornwall (National Trust regional history series)

1. Cornwall History

I. Title II. Series

942.37 DA670.C8

Hardback ISBN 0 00 218059 6

Paperback ISBN 0 00 218104 5

First published 1984

Copyright 1984 Jack Ravensdale

Made by Lennard Books

Mackerye End, Harpenden

Herts AL5 5DR

Editor Michael Leitch

Designed by David Pocknells Company Ltd

Production Reynolds Clark Associates Ltd

Printed and bound in Spain by

TONSA, San Sebastian

Cover Photographs

Centre: Lands End

Top left: St Agnes

Top right: Port Quin

C ONTENTS

Cornwalls unique rock structure;

Imperial life in Western Britain;

Social patterns in the Kingdom of Dumnonia;

The medieval tin-streamers;

Norman and Tudor castles;

From twelfth-century Earldom to modern Duchy;

Prince Charles revives an ancient ceremony.

Early parish churches;

Chapels, oratories and shrines.

After the Dissolution, palatial houses from monastic plunder;

Elizabethan and later buildings and gardens;

Medieval market centres;

The Cornish rebel against punitive taxes of Tudor kings and the enforcement of Protestantism;

Failure of the risings;

Brutal pacification of the county.

Changing fortunes of the miners;

First finds near St Austell;

Growth of the industry;

New applications today.

Decline of traditional industries;

China clay and tourism, staples of future growth.

E DITORS INTRODUCTION

One can holiday in a seaside resort in Cornwall and yet learn no more about the Cornish and their land than the package-tripper to Benidorm finds out about Spain. Newquay and Penzance can be welcome havens at the end of a long for many, a surprisingly long journey, but just beyond the resorts there is a countryside of rugged beauty which is packed with interest and historical details and is still, in most places, reasonably unspoilt.

Cornwall has its own language, culture and outlook and a powerful individuality; its scenery is unique in Britain, and to see a remotely similar countryside one must travel across the sea to another Celtic bastion, Brittany. It is also a place where reality is far more fascinating and diverse than the popular perceptions suggest. Hidden coves, where smugglers and wreckers lurked, and dubious Arthurian fantasies tend to dominate the visions of outsiders or up-country folk, and while the coastline is the equal of any and the folklore as rich and unlikely as can be, the real Cornish landscape and history have been strangely neglected by the public in general.

Although its terrain is relatively gentle, Cornwall is indisputably a part of upland Britain a land of damp and rather impoverished soils, offering only the most modest returns for the farmers hard labour: a place where mining and quarrying have, for all their dangers, lured many toilers from the land. Cornwall offers the visitor a remarkable portfolio of monuments. The prehistoric legacy of small tombs and circles could scarcely be surpassed, and if the Roman endowment is meagre, there are some tough little medieval castles, a few quite exceptional mansions and a most remarkable heritage of industrial relics.

Jack Ravensdale has provided a colourful but authoritative account of the Cornwall which the holidaymaker so often misses. His work as a historian and as author of the scholarly study of a group of Fen-edge villages, Liable to Floods, has won him the esteem of many professional historians. But Jack is a most modest person, and, although he has been a good friend since we worked together on some photographs for his best-seller, History On Your Doorstep, it took a special call to extract brief biographical details. After completing his degree at Cambridge University, he became an adult education tutor with the WEA, covering north and mid Cornwall and living in Wadebridge and Minions. In the course of those seven years he developed a close understanding of the creation of the Cornish landscape and he maintains his contacts with the area in the course of periodic visits to his numerous Cornish cousins. On leaving Cornwall he taught in Cambridgeshire, becoming Principal Lecturer in the History of the English Landscape at Homerton College and receiving a doctorate in 1972 from the University of Leicester where he had been working part-time in the Department of English Local History. In 1981 he retired from teaching in order to develop an expanding career as a writer.

Richard Muir Great

Shelford, 1983

T HE ENDOWMENT

Cornwall was bound to be different: its rocks had made it so. They are of several kinds and have different origins, but it is the grey granite which dominates Cornwalls landscapes and moods.

The story of the rocks began around 400300 million years ago, in the Devonian and Carboniferous periods, when the land that is now Cornwall lay beneath a sea. Sediments deposited in this sea accumulated to produce the Devonian shales and limestones of north Cornwall and Devon and the Carboniferous sandstones and mudstones which form the greater part of the surface geology of Cornwall. At the end of the Carboniferous period, around 290 million years ago, great earth movements centred further south in Europe thrust an enormous mass of molten rock or magma from far below the surface of the earth into the zones underlying the Cornish landscape. The sedimentary rocks above were bulged upwards, and wherever they came into close contact with the searing magma they were scorched and changed or metamorphosed.

The magma cooled and solidified to form a great underground mass or batholith of granite, which originally lay about 8miles (12km) below the surface. In the course of the subsequent millennia, erosion has stripped away the rocks covering the higher domes or cupolas of the batholith, and the granite has been exposed to form the distinctive moorstone landscapes of the Scilly Isles, Lands End, Carnmenellis, St Austell, Bodmin Moor and, in Devon, Dartmoor. Masses of rotted granite, decomposed by scalding waters released by the cooling magma, form the white kaolinite or china clay deposits which are quarried at the domes of the granite outcrops where the water was vented. No well-sited china clay pit has ever reached the bottom of the deposit, and the finest-quality Cornish clays are unequalled elsewhere in the world. When Cornwall arose from the ocean the good fairies were unusually active.

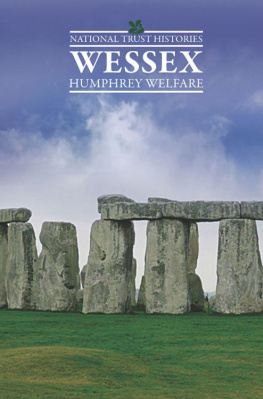

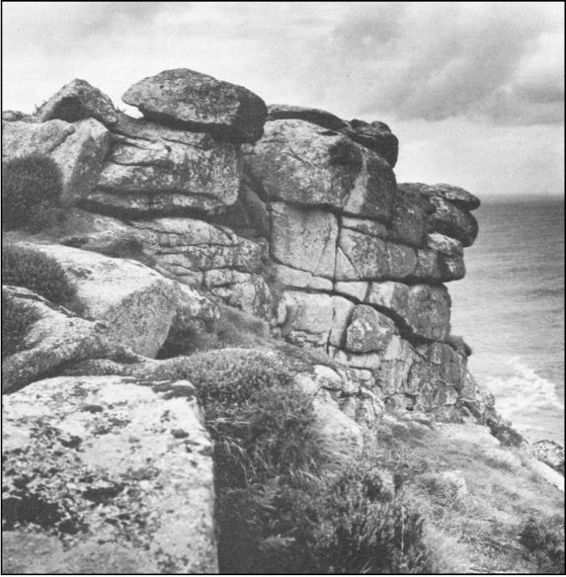

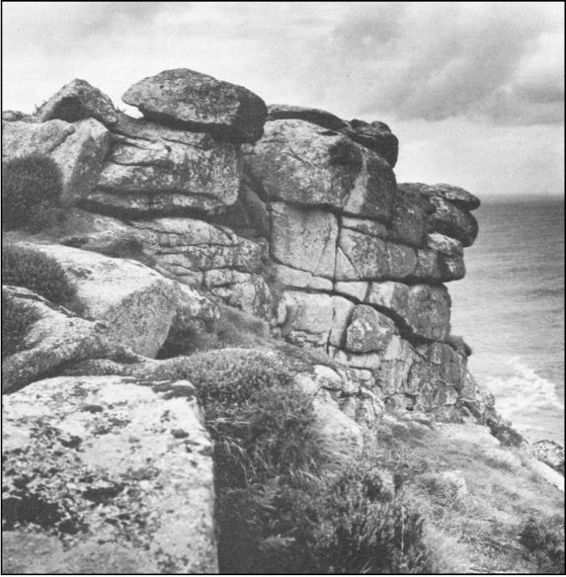

Cliffs at Bosigran. Granite outcrops such as this display a clear system of joints, and the cracks seem to have opened as a result of the release of pressure when erosion removed the heavy overburden of rock.

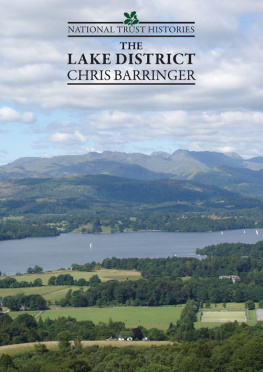

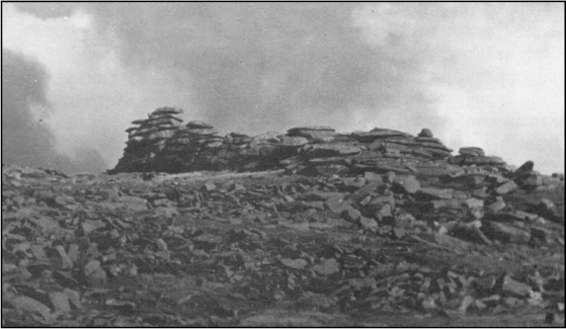

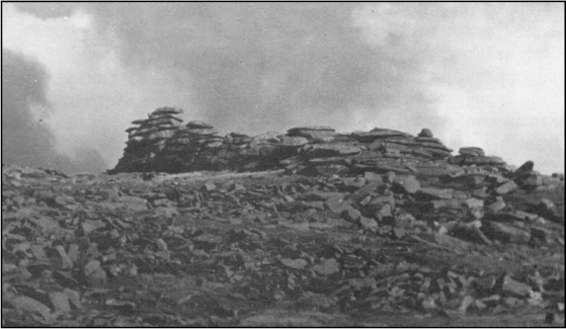

Rough Tor, on Bodmin Moor, is the second highest Cornish tor and looks over a remarkable concentration of hut circles and compounds from the Bronze Age, and field systems dating from every period since then.

Different rocks are found at the Lizard, where a great thrust has forced up serpentine, gabbros and schists. These varied rocks have long been valued by man and were exploited in prehistoric times by the makers of prestigious greenstone axes; since they weather into valuable and distinctive clays, they have also been exploited by potters for thousands of years.

Next page