Contents

Guide

Pages

Rummage

ALSO BY EMILY COCKAYNE

Cheek by Jowl: A History of Neighbours

Hubbub: Filth, Noise & Stench in England

EMILY COCKAYNE

Rummage

A History of the Things We Have Reused, Recycled and Refused To Let Go

First published in Great Britain in 2020 by

PROFILE BOOKS LTD

29 Cloth Fair

London EC 1 A 7 JQ

www.profilebooks.com

Copyright Emily Cockayne, 2020

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Typeset in Garamond by MacGuru Ltd

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78125 851 4

eISBN 978 1 78283 357 4

This book is dedicated to the memory of Evelyn Bradbury

(19231992)

1

Time Up for Master Humphreys Clock

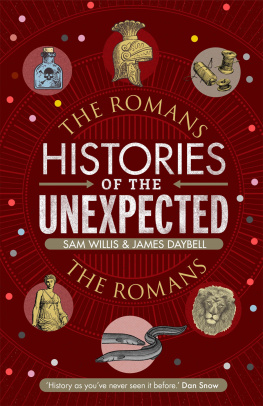

I ventured into the back room of my local second-hand bookshop for the first time a few years ago, lured by the promise of a special set of books. Dusty piles of old leather-bound tomes surrounded me as a jolly woman stood on a chair to reach down a first-edition three-volume set of Charles Dickenss weekly serial Master Humphreys Clock, published in 1840. I had located the volumes online and had been pleasantly surprised to see they were so close to home. I inspected them. The third volume had been repaired some time in the twentieth century; a tell-tale flash of purplish backing peeped out under the brown of the original spine. I wondered what had happened to that volume, to render it in need of repair when the other two had not been. What lives had these volumes lived? I do not know how many people had owned them before me; there are no inscriptions. I do know what happened to another set from the same printing litter during the Second World War. That came within a whisker of being pulped for the war effort. Such books are not only relics of the past; they each contain the history of their own survival.

1. Master Humphreys Clock (1840). Authors collection, photographed by Taryn Everdeen.

In 1942 James Ross, the City Librarian of Bristol, was tasked with examining and sorting books donated to the citys Salvage Drive. During the drive, books came from all over: some volumes were collected by children at school; others were gathered through house-to-house collections; some were pulled from papers donated to a paper mill. Sorting through the heaps, Ross and his team consigned volumes to one of four piles. Some were to be sent to the troops, each stamped with To Fighting Forces wherever you may be. With best wishes from the citizens of Bristol, England. Others went to re-stock war-damaged libraries. A portion were deemed valuable enough to be saved without further reasoning as to their use. The rest were pulped or used in munitions-making and packing. One fated afternoon, Ross will have flicked through Master Humphreys Clock. The text is narrated by a lonely misshapen deformed old Londoner who hoards piles of dusty papers in his beloved clock, and believes butterflies will generate in some dark corner of these old walls. Ross, with the Ministry of Supply instructions before him, put the Dickens volumes in the to be saved pile with other books he deemed to be hard to obtain, rare, valuable or of bibliographical value. By the end of the war, Rosss team had received over a million books. Countless editions of classics were pulped to make boxes for munitions or heating pipes for bombers. Through a combination of sheer luck and the efforts of people like James Ross, some treasures including the set of Dickens I then clutched in the back of a bookshop survived. Recycling is not only about economic or ecological value. It involves cultural judgement, social norms, taste and memory. In an emergency, what would seem too precious or inconvenient to scrap, even in the face of existential threat?

Every future is, to some degree, a bricolage of the pasts uncertain remnants. History was once the study of the victorious. In the world of objects, antique furniture and paintings by the masters are victors of a kind; they gain value and become more cherished. Sometimes, as in the case of Master Humphreys Clock, the fact that they came so close to destruction seems to imbue objects with a special worth. But the vanquished and the forgotten have value of their own. More recently, neglected people have finally received more attention from historians and, in parallel, things previously deemed irrelevant or commonplace have acquired new significance. In every age, complicated but everyday judgements are made about the usability of things: what to keep and what to discard. The relative value of leftovers constantly changes, influenced by the hopes, expectations and needs of human communities, whether we are looking at the stories, people or objects to carry from the past into the present. Rummage is about material redemption. It is a history of the reused, a history of extraordinary reinvention.

This book begins with Master Humphreys Clock not only because it has survived the past, or because its narrator is a thrifty hoarder, but because the book itself is a paragon of reinvention. The majority of materials that came together to make it, like most books published before the end of the nineteenth century, were recycled. Bound in brown cloth, Master Humphreys Clock has covers adorned with an embossed image of a clock and pages printed on paper made from linen rags. The binding glue was made from animal by-products, and even the gold used to emboss the clock may have come from floor sweepings. After the late nineteenth century, most books included a relatively insignificant fraction of recycled content: their paper was made from virgin wood pulp. Books often exemplify broader changes in the practices of reuse and recycling.

Rummage focuses on the material transformation of things, especially ingenious repurposing and material remodelling. That could include recycled materials, such as the linen rag used in books, and also waste products put to a first use. The latter are not, strictly speaking, examples of reuse, because they involved little in the way of processing in order to be put to use. Still, some slip into the narrative because the public and the politicians did not always discriminate. This can be seen in the way salvage during the wars included the use of human food waste for pigs, and the use of old bones to manufacture glycerine. Such processes influenced broader attitudes to the often grimy and grubby work of recyclers. The story I will tell is as much about these changing attitudes as it is about material objects.