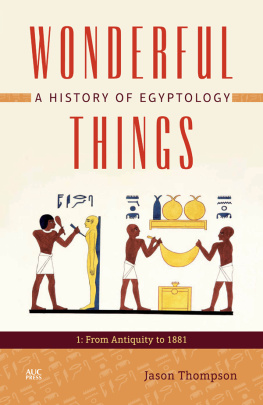

WONDERFUL THINGS

WONDERFUL THINGS

A HISTORY OF EGYPTOLOGY

1: From Antiquity to 1881

Jason Thompson

The American University in Cairo Press

Cairo New York

This electronic edition published in 2015 by

The American University in Cairo Press

113 Sharia Kasr el Aini, Cairo, Egypt

420 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10018

www.aucpress.com

Copyright 2014 by Jason Thompson

First published in hardback in 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 978 977 416 599 3

eISBN 9781 61797 636 0

Version 1

To the memory of Susan Howe Weeks, artist, Egyptologist, friend, and neighbor

Contents

S o many people and institutions have been helpful in this project that I hesitate to mention them for fear of leaving any out, but I must try to acknowledge my gratitude to friends, colleagues, and fellow workers who have helped me find my way. By resorting to alphabetizing, I seek to avoid any suggestion of favoritism. First there are those whom we have lost in recent years. Those include Vivien Betti, Gaballa A. Gaballa, T.G.H. (Harry) James, Jacobus (Jac) Janssen, Jean Leclant, Robert Lucas, and Susan Weeks.

Those who, thankfully, do not yet fulfill the final qualification for entry into Who Was Who in Egyptology include Jeffrey Abt, Lawrence M. Berman, Morris L. Bierbrier, Peter A. Clayton, Lorelei H. Corcoran, Agnieszka Dobrowolska, Helen Dorey, Stephen Edidin, Elizabeth Fleming, ric Gady, Jocelyn Gohary, Diane Harl, Zahi Hawass, Marsha Hill, Olaf Kaper, Joanna Kyffin, Rosalind Janssen, Janet H. Johnson, Michael Jones, Jack Josephson, Roger O. de Keersmaecker, Peter Lacovara, John Larson, Briony Llewellyn, Julian Lush, Diana Magee, Deborah Manley, Anthony J. Mills, Chris Naunton, Hana Navrtilov, Yvonne Neville-Rolf, Edward OReilly, Patrizia Piacentini, Patricia Podzorski, Stephen Quirke, Caroline M. Rocheleau, John Ruffle, Edna R. Russman, Jiina Rov, Mona Sadek, Wafaa el-Saddik, Helmut Satzinger, Sarah Searight, Caroline Simpson, Patricia Spencer, John H. Taylor, Emily Teeter, Eric Uphill, Patricia Usick, Marie-Paul Vanlathem, Miroslav Verner, and Emily Weeks.

I also want to thank the students in my History of Ancient Egypt classes at Colby College and Bates College for many inspiring moments that contributed to this book.

Scholars and writers who have read all or part of the manuscript and contributed to it in other ways include Neil Cooke, Abdalla Hassan, Jill Kamil, Peter Der Manuelian, Stephanie Moser, Andrew Oliver, Margaret Ranger, Maarten J. Raven, and Kent R. Weeks.

My wife, Angela, was my companion and sometimes coworker on several archival expeditions. My nine-year-old son Julian was an able research assistant in the field, although I might here complain that it was sometimes hard to keep pencil and paper since he was constantly appropriating them to make notes of his own at every site. I am more grateful to Angela and Julian for those shared experiences than I can express.

I owe a special debt of gratitude to Jaromir Malek, the person who is assuredly the most qualified to write a history of Egyptology. Without his approval, encouragement, and advice, I would never have undertaken to write one myself, nor would I have persevered in the effort.

At the American University in Cairo Press, Mark Linz, who also must be acknowledged in memory, and Neil Hewison were encouraging, supportive, and infinitely patient from the first in an undertaking that grew much larger and took much longer than we anticipated at the outset. Mark was enthusiastic about this project from the start. I might never have attempted it otherwise. I also wish to acknowledge the project editor, Johanna Baboukis; the copyeditor, Nell McPherson; the proofreader, Eva Abdin; and the indexer, lfwine Mischler. But none of the above should be considered guilty by association. I am fully responsible for all mistakes and shortcomings.

Institutions that have provided materials for this book includein no alphabetical or preferential orderthe Griffith Institute of the Ashmolean Museum, the Bodleian Library, the Cambridge University Library, the British Library, the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, the Epigraphic Survey of the University of Chicago, the Egypt Exploration Society, the American Research Center in Egypt, the New-York Historical Society, the Archives of the British Museum, the Archives of the Department of Ancient Egypt and Sudan at the British Museum, the Department of Egyptian Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Dakhleh Oasis Project, the Oriental Museum of the University of Durham, the Archives du Muse Nationale at the Muse du Louvre, the Sir John Soane Museum, the Brooklyn Museum, the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, the Egyptian Museum of Cairo, the Kunsthistorisches Museum of Vienna, the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden in Leiden, the Institute of Egyptian Art and Archaeology at the University of Memphis, and the Department of Egyptian, Nubian, and Near Eastern Art at the Michael C. Carlos Museum at Emory University, the Deutsches Archologisches Institut Kairo, and the Institut Franais dArchologie Orientale.

Awards from the American Research Center in Egypt, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the Bates College Faculty Development Fund provided valuable support for portions of my research.

Note

Spellings of pharaonic names are primarily followed from those in John Baines and Jaromir Malek, Atlas of Ancient Egypt. Transliterations of Arabic names and words are generally given in simplified form without diacritics or ayns. Unless otherwise indicated, translations are by the author.

Jaromir Malek

S ome years ago I gave a small talk to a group of Egyptologists at an old and famous German university. The subject was the Egyptological archive of the Griffith Institute in Oxford, the largest of its kind in the world, of which at that time I had the honor and pleasure of being Keeper. The thesis which I tried to promote in my lecture was that the maturity of a scholarly subject can be judged by how it treats and looks after its sources of information. For Egyptology, these may still be in situ in Egypt or be removed to museums, collections, laboratories, and storerooms, but they also include archive records, such as early copies of inscriptions and representations on tomb and temple walls, photographs, tracings, squeezes, and descriptions of sites and monuments. In this respect, I ventured to suggest, Egyptology had not yet fully matured. After the talk the professor of Egyptology at that university, a brilliant and much respected scholar, came to me and said, There is one other thing by which the maturity of a subject can be judged, and that is whether it has a written history. These words have remained with me ever since. And indeed, Egyptology has in this respect been wanting. A comprehensive history of Egyptology has until now not been attempted. The main reason, no doubt, has been the huge and immensely varied amount of material with which one would have to come to terms and the almost encyclopedic knowledge required for controlling it.

It is therefore good to see the first volume of a work which promises to take us a long way toward the fulfillment of our wish. Its author, Jason Thompson, is eminently suited for the task. He has contributed to various aspects of the history of Egyptology on many occasions in the past. His monographs on E.W. Lane and Sir John Gardner Wilkinson take pride of place in the literature dealing with this subject, and he has also written on, among others, Sir William Gell, Frederick Catherwood, and Donald Thomson, alias Osman Effendi. Most importantly, his training in history enables him to place various advances in the subject unerringly in the overall geopolitical context of the period in order to present a broader view of the trends, results, and missed opportunities.