Featuring three new stories: The Accident, Location, and Armistice Day.

W e mark the eras of human history by our technologiesStone Age, Iron Age, Information Ageand we often mark the eras of our own lives by our technologies as well. I place a memory in context by recalling the car that I drove at the time, and a life-changing phone call is remembered, in part, by the shape of the phone that I gripped. An important aspect of my memory of 9/11an event made possible by the intersection of some specific technologiesis hearing about it on the radio, and then searching for a television where I could see the news, and finally of watching the towers fall on a tiny, silent cathode ray TV set on the counter at a diner.

We assume that the progress of time turns technologies into history, but perhaps it is the other way around, and without the progress of technology we would have no history. In the film Cave of Forgotten Dreams, Werner Herzog shows two Neolithic paintings that are located on the same cave wall and appear so identical in style they might have been painted by a single artist. But carbon dating has shown that they were painted 5000 years apart. Herzog, in a voiceover, observes that the paintings indicate a people who lived outside of history. Time was a circle, until the rapid evolution of our machines pulled it straight, and if our technologies define the line of the past, then we assume that they will do the same in the future. In 1999, I was in a writing workshop where another student, Antoine Wilson, submitted a short story titled It Is the Business of the Future To Be Dangerous. I particularly envied that title. Later, I learned that the phrase comes from the writings of the philosopher Alfred North Whitehead. It is the business of the future to be dangerous, Whitehead wrote, and it is among the merits of science that it equips the future for its duties.

The future seems more dangerous than the past because we cannot imagine what we will soon invent, or even the consequences of the things we have recently inventedwhether the effects of social media, the emissions of our engines, or the ramifications of artificial intelligence. But the only solutions we consider involve different technologies, new technologies, more technologies. To go backward is impossible, for a thousand reasons. The rush of progress is larger than any one of us, a dumb behemoth; where it will lurch next, we can only guess, and even the engineers, scientists, and programmers who feed it are helpless to stop it, can only hope to give it the slightest of nudges.

I wrote the stories collected in In the Electric Eden during the years 1998 to 2001, and the book was first published in 2003. At the time I intended for only two of the stories in the collection to be considered historical fiction, but looking at it now I see that time makes all fiction into historical fiction. The stories that were contemporary when I wrote them rely on technologies and devices that now seem quaint, or soon will. They record a world where many of us didnt own a cell phone; voicemail was a relative novelty; YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter didnt exist; and Amazon was a website that sold books. I remember I was sitting at a desktop computer searching the internet when I stumbled across a video of Thomas Edisons 1903 film of Topsy the elephants electrocutionfeatured in the title story of In the Electric Edenand the fact that I could watch a video on an internet website still seemed remarkable to me.

By that time I had studied engineering in college, and I had worked for a couple of years in product development at Ford. Engineering was a career I had stumbled into, based on a knack for math and science and a vague attraction to the idea of building things like rockets and airplanes. But Id grown up in a little Midwestern town where I didnt know any actual engineers, and I had no practical experience with what they did day-to-day. Becoming an engineer was like parachuting into a strange tribe with its own language, customs, and habits of thinking. It was interesting to observe these people, and to consider the effects of the things we were creating, how the things we make in turn remake our lives, our feelings, our souls.

Fiction has always been my means, or mechanism, for grappling with the world, asking questions, trying to find patterns and threads of sense. It is in our nature to understand ourselves and our world through our stories, and as we shape our stories, our stories in turn shape us, in a restless cycle. Stories and technologies are similar in this way, two feedback loops between creators and creations, two conversations we are having with ourselves.

Engineers who write fiction are relatively rare, and many of the engineers who do write fiction favor science fiction, which often reflects on the same themes Ive mentioned here. My own stories are set in the past or the present, but it is all of a continuum: the present is the science fiction of the past, and fiction describing tomorrow is the historical fiction of tomorrows tomorrow.

In one of the stories in this collection, a character in the eighteenth century marvels at a new technology that allows a man to fly. He observes, The hard shell of the impossible had been cracked, and who could say what might appear next? I believe that, whether we are noticing it or not, the hard shell of the impossible is cracking every day; these stories are an attempt to notice.

Nick Arvin

2018

Progress, therefore, is not an accident but a necessity. It is a part of nature.

Herbert Spencer

I, though interested in diesel engines, did not take my eyes off the girl.

Max Frisch

M y grandfather Henry kept an unusual umbrella stand beside his front door. Encased in seamless gray leather, it appeared coarse-grained and lusterless in the shadowed corner where it stood. Beneath my fingers it felt rough and slightly bumpy. Generally cylindrical, it widened at the bottom, like a tree trunk, or an elephants footwhich it was. Topsy had been the elephants name.

Recently, I received an e-mail that started me thinking about the umbrella stand again, and I began to do some research, in the library, on the Web.

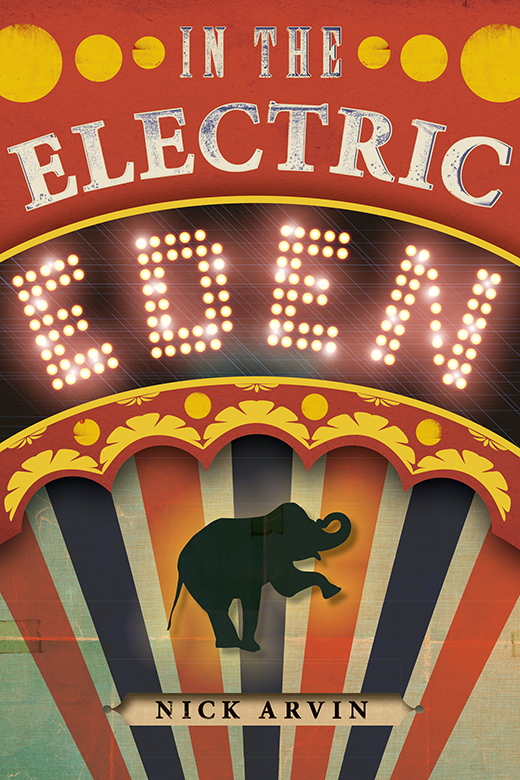

One central fact can be agreed upon: they Westinghoused Topsy on the grounds of Luna Park, Coney Island, on Sunday, January 4, 1903. But the histories and novels tend to depict the event with bright lights and blazing colors, offering in it a symbol for all the excesses of Coneys heyday. We see an elaborate stage, a giant switch labeled 100,000 Volts, bleachers filled with cheering spectators at ten cents a head. Thomas Alva Edison, the Wizard of Menlo Park himself, presides. A score of men strain against ropes as big around as their arms to bring Topsy into position. For a warm-up she eats bushels of cyanide-laced carrots and shakes them off. In the background Luna Parks quarter million electric bulbs burn against a dark sky, transforming night into noon and providing the park with its advertising sobriquet: The Electric Eden. The execution switch is thrown and two hundred and fifty thousand filaments flicker and dim.