For R.G.H. and C.R.A.

A crying of tires erupted from the street.

The two boys in the house froze and waited, listening. A high wooden fence surrounded the subdivision where they lived; on the other side lay what they called the big streets . Between their backyard and the intersection of Mill and Main stood only the wooden fence and a hundred feet of sidewalk.

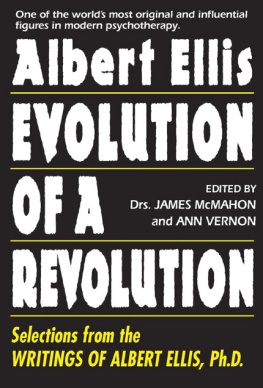

Tires squalled and cried toward the intersection, and Ellis and Christopher waited. They had done this before. Accidents occurred there often.

This was when they were young, and they still played together.

Then the collision ripped the air open for one roaring instant, and the boys startled, and the glare on the television glass trembled. It ended with a lingering metallic sound, like a rolling paint can, that drifted away, and silence resumed. The boys stampeded the door.

They ran nearly a quarter mile until they reached an opening in the fence, then turned into the big streets where a line of unmoving traffic was already forming, car behind car, drivers staring toward the intersection. Ellis wheezed and felt the shortness of his legs relative to Christophers, but he kept up. A sirens howl drew toward the intersection from the other side of town.

Two boxy American sedansa Chevy and a Plymouthlay in unnatural postures, pointed in oblique directions, their black guts exposed, their glossy surfaces crumpled, twisted, torn. An acrid odor filled the air. Radiator fluid the color of green Kool-Aid glistened in an arc on the asphalt. Across the intersection lay a single shining hubcap. It matched the chrome hubcaps on the nearest sedan, the Plymouth, where a fat man and his fat wife stood. The husband peered toward the approaching sirens while his wife glanced at her watch, repeatedly, and Ellis wondered why she was barefoot. Near the Chevy were two women. One, older, was comforting the other, a young woman with heaps of hair who lay on her back on the street and held her hands over her face and moaned and cried out to God for help.

A few people gathered on the corners. Two more boys from the neighborhood arrived and joined Ellis and Christopher. A third. They punched one another on the shoulders.

A policeman picked up the hubcap and directed traffic around the damaged vehicles. Another policeman talked to the women in the Chevy and scribbled on a notepad.

An ambulance arrived. The woman holding her face and moaning was placed onto a gurney and swallowed by the ambulance. A wrecker with flashing amber lights backed up to the Plymouth while the ambulance moved off with its siren alternating yowls, bleeps, and squawks.

The twins trotted in, and they were punched on the shoulders, too.

The sedans trundled away behind a pair of wreckers. A cop remained, taking notes, talking with people. He measured distances with a wheel on a stick that he rolled from point to point. He retrieved a camera from the trunk of his cruiser and took photos.

Go home, he shouted toward the boys.

They sidled a few steps down the sidewalk and loitered there. Only when this cop, too, had climbed into his car and driven away did Christopher start to saunter off.

The others followed. The short twin was pushed and he stumbled. Leave me alone, he protested, and the others laughed. They shoved one another and pretended to trip, flailed around, clutched one another. One of the boys jogged backward in front of the short twin and chanted in his face, Leave me alone. Leave me alone. Christopher veered over and hit Ellis with his shoulder and shouted, Smash!

Ellis bounced into another boy, yelling, Crash!

Christopher surged into the tall twin and screamed, Wham!

The boys tumbled together headlong down the sidewalk, pinballing and roughly chanting, Smash! Crash! Wham! Bash! Crash! Slam!

The tall twin screamed, Boom! A boy shouted, Wreck! Another hollered, Blood! And another yelled, Guts! They punched one another on the shoulders and shook their fists as if on a team that had won. They began to sprint and strain for speed.

The next day, Ellis rode through the intersection with his mother in her Oldsmobile. The damaged vehicles were gone, of course, and the splash of green fluid had vanished, too. The only indications of the collision were a couple of short dark tire marks on the pavement and, at the corners of the intersection, the shards of glass and broken ruby-colored plastic pushed by passing tires into long shallow piles.

On his lap Ellis Barstow held the police photographs of Pig Accident Two. Hed sorted them into three groups of about a dozen images each. The first group showed, from various angles, the accident vehiclea white Mercedes lying a short distance from the large pine tree that had smashed in the drivers door. In the second group was vehicle-path evidenceblack tire marks deposited on the asphalt as the Mercedes skidded and yawed before going off-road, and the furrows that the wheels had cut through the soft earth leading to the tree. And in the last group were roadway obstructionsthe scattered carcasses of a half dozen crushed and bloody wild pigs.

Ellis also held a rough, hand-sketched diagram of the accident scene. It had been made by the police, and it showed measurements locating the Mercedes, the tree, and the tire marks. He kept turning from the photos to the diagram and back again, with a vague impression of something anomalous. He couldnt identify its origin.

He and Boggs, his boss, had boarded the airplane in the purple darkness of early morning; now, as they banked, the first red light of the sun burst in the window. They were flying from the humid summer of Michigan to the humid summer of Wisconsin, to land in Milwaukee at eight in the morning. Ellis sat on the aisle, and next to him sat a young couple, a woman who wore a hair product that smelled like some obscure fruitpapaya, maybe. Next to her was a man with tattoos all over his arms. The two of them argued in undertones. When the womans elbow nudged Elliss on the armrest, he flinched and hunkered down. He didnt want to be distracted. He wanted to see the diagram and the photos completely and, further, to see the physics that they implied.

Boggs sat two rows up, his big hairy head tilted backward, asleep. At the airport that morning, while theyd waited for the flight to board and Boggs clipped his fingernails, dripping little white trimmings onto the airport carpet, hed declared that he hated waiting and he hated waiting in airports and he hated airports. The only viable emotion in an airport is anxiety, he said. You come into the airport and you feel anxious or you feel nothing.

I dont know. What about irritation? Ellis suggested. And boredom.

Boredom seems awfully close to the feeling of feeling nothing. But, irritationyeah, I suppose youre right.

And now Im feeling the thrill of being right.

Boggs worked at the nail on his thumb. Even if I were feeling irritated, he said, I wouldnt admit it.

A couple of the photos on Elliss lap were close-ups of one particular pig, the largest, a boar about four feet long from snout to tail, with a bristling razorback and tusks as big as a mans finger. Positioned more or less in the center of the lane, it lay on its side with one leg bent back underneath and an eye smashed in. This appeared to be the specific pig that caused the driver of the Mercedes to swerve. Ellis turned through the photos again. It looked like there was room to steer around the pig, through the roads shoulder.

Ellis noticed suddenly that the papaya-scented woman beside him was ignoring her companion and gawping at the photos. Reluctantly, he put them away.