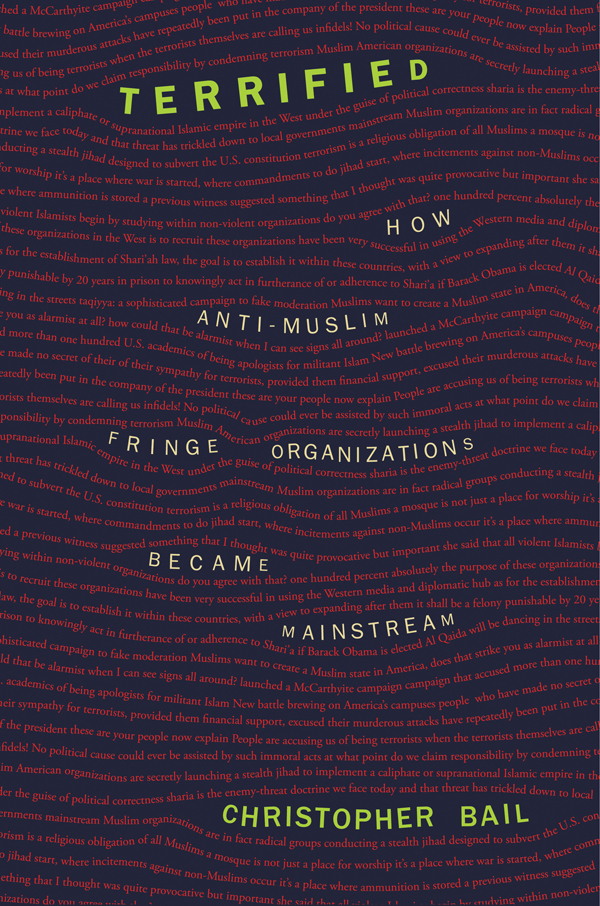

TERRIFIED

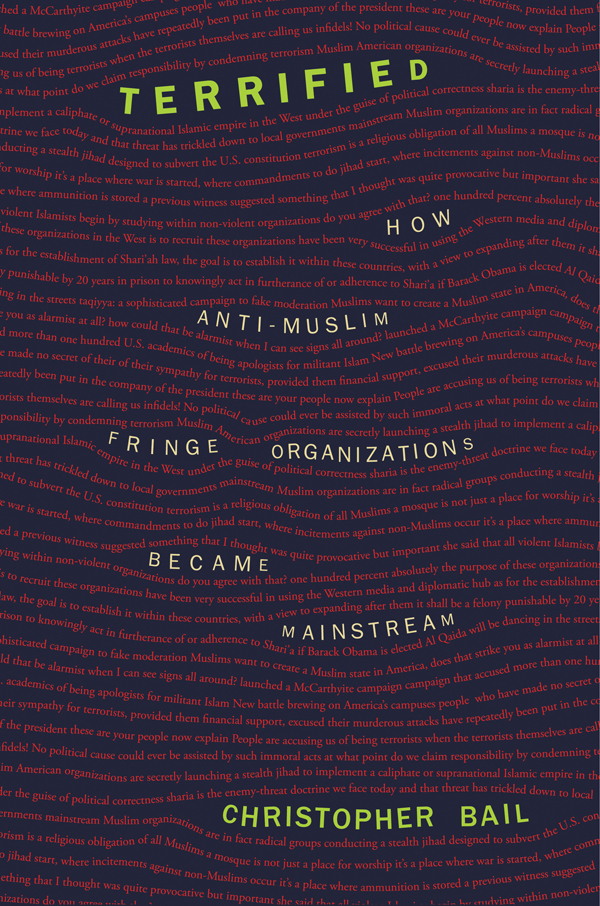

TERRIFIED

How Anti-Muslim Fringe Organizations Became Mainstream

CHRISTOPHER BAIL

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2015 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-15942-3

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014947502

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Franklin Gothic and Charis

Printed on acid-free paper

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

TABLES

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

T HIS IS A BOOK ABOUT HOW CIVIL SOCIETY ORGANIZATIONS shape the evolution of public discourse about social problems after major crises such as the September 11th attacks. One of my principal arguments is that civil society organizations achieve most influence upon public discourse when the evolutionary forces that made them powerful become invisible. If this book influences how people think about the evolution of public discourse, it will be thanks to the many colleagues, universities, funding agencies, family, and friends who helped make this work possible.

This book was first conceived undergroundbetween the labyrinthine walls of Harvards Pusey Library. My self-imposed exile was part of an artless attempt to impress my mentor, Michle Lamont, by reading every social science manuscript within sight. With characteristic brilliance and good charm, Michle soon convinced me that the most important discoveries are made above ground, in the wondrously messy world of empirical observation andperish the thoughtinteraction with other social scientists. I soon found myself enjoying eclectic conversations with Orlando Patterson, whose encyclopedic wit nurtured my burgeoning interest in public discourse about Islam. William Julius Wilsons legendary enthusiasm emboldened me to attempt a wholly unreasonable dissertationin both scope and substance. I was therefore fortunate to convince Jocelyn Viterna to serve on my dissertation committee; she helped me focus my broad interests within the literature on collective behavior with generous enthusiasm and acumen. Yet it was Mary Waters who helped me realize the metamorphosis of my dissertation into this book, and the near total transformation that such efforts require.

As is perhaps common, my education in graduate school stretched far beyond my dissertation committeeand so too the family of people who inspired this book. I was particularly fortunate to learn from Jason Beckfield, Neil Gross, and the inimitable Stan Lieberson. I also enjoyed the wisdom and collegiality of Mary Brinton, Frank Dobbin, Peter Hall, Sandy Jencks, Tamara Kay, Gary King, Peter Marsden, Rob Sampson, and Chris Winship. I am likewise very grateful that Andreas Wimmers sojourn within Harvards sociology department coincided with my time there, since he remains one of my most trusted critics to this day. This book also benefitted from conversations with many other graduate students at Harvard: among many others, Cybelle Fox, Marco Gonzalez, David Harding, Simone Ispa-Landa, Kevin Lewis, Mark Pachucki, Lauren Rivera, Wendy Roth, Pat Sharkey, Graziella Silva, Cat Turco, and Natasha Warikoo.

Though this book was born in Cambridge, it came of age in Ann Arbor, where I spent two blissful years at the University of Michigan as a Robert Wood Johnson Scholar. At Michigan I enjoyed many long conversations about this book with Elizabeth Armstrong, Sarah Burgard, Christian Davenport, Jerry Davis, Mge Gek, David Harding, Vince Hutchings, Rob Jansen, Victoria Johnson, Greta Krippner, Karyn Lacy, Sandy Levitsky, Mark Mizruchi, Jeff Morenoff, Jason Owen-Smith, Norbert Schwartz, Peggy Somers, Kiyoteru Tsutsui, and Fred Wherry. I was also particularly fortunate to benefit from the generous and cheerful mentorship of Mayer Zald during the last year of his life. I spent most of my time, however, enjoying interdisciplinary cross-pollination with my colleagues in the Robert Wood Johnson Program: Jane Banaszak-Holl, Rachel Best, Graeme Boushey, Seth Freeman, Alice Goffman, Rick Hall, Daniel Lee, Jamila Michener, Sarah Miller, Dan Myers, Edward Norton, Brendan Nyhan, and Francisco Pedraza.

I completed this book during my first year as a junior faculty member in the sociology department at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. This was an ideal locale to finish this manuscriptnot only because of the unparalleled strength of my colleagues within cultural and political sociology such as Andy Andrews, Neal Caren, Daniel Kriess, Charlie Kurzman, and Andy Perrin, but also because of the tremendous warmth and inspiration of my colleagues from other subfields. Though I would eagerly acknowledge the support and encouragement of each one if space allowed, I must at least thank the following people for conversations that helped improve this book: Howard Aldrich, Jackie Hagan, Kathie Harris, Arne Kalleberg, and Laura Lopez-Sanders.

Numerous colleagues offered written criticism of this work in its early, intermediate, and advanced stages. I am most indebted to Randall Collins, Heather Haveman, Daniel Kriess, Charlie Kurzman, Terry McDonnell, Francesca Polletta, Iddo Tavory, and Haj Yazdiha for reading the entire manuscript. Andy Andrews, Elizabeth Armstrong, Avi Astor, Rachel Best, Mehdi Bozorghmehr, Michaela De-Soucey, Neil Gross, Rob Jansen, Brayden King, and Andy Perrin offered generous comments upon individual chapters as well. Yet this book also benefitted from dozens of conversations with the following colleagues from an invisible college: Mabel Berezin, Amy Binder, Grard Bouchard, Karen Cook, Paul DiMaggio, Jennifer Earl, John Evans, Roberto Franzosi, Jennan Ghazal Read, Amin Ghaziani, Ron Jacobs, James Jasper, Colin Jerolmack, Riva Kastoryano, Paul Lichterman, Omar Lizardo, Doug McAdam, Ashley Mears, John Mohr, Charles Ragin, Gabriel Rossman, Patrick Simon, Chris Smith, Phil Smith, Brian Steensland, Ed Walker, and Patrick Weil.

Several organizations provided financial support for this book. The National Science Foundation, the Harvard Divinity School, and the Horowitz Foundation for Social Policy generously supported my fieldwork. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation freed me from teaching and committee responsibilities for two years, providing me with the time and space necessary to collect new data and hone my argument. The foundation also enabled me to hire two outstanding research assistants, David Jones and Nate Carroll, who assisted me in data collection, analysis, and editing of this book. I am also indebted to Taylor Whitten Brown and Matt Mathias, who assisted me in the analysis and writing of this book at various stages. Jenny Wolkowicki, Ryan Mulligan, and Joseph Dahm ushered the manuscript through the final stages of production at Princeton University Press.

Finally, I owe a deep debt to my incomparable editor, Eric Schwartz. His vision, patience, and steady hand helped me navigate the odyssey of writing ones first book. Yet my greatest debt is to my wonderful partner, family, and friends. Whenever I was frustrated by obstaclesoften self-createdthey reminded me that I would enjoy their love and respect, no matter what the outcome of my work.

ACRONYMS

AAADC | American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee |

AAAS | American Association for the Advancement of Science |

Next page