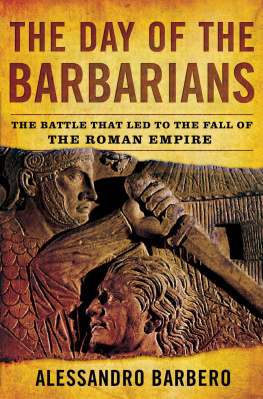

THE DAY OF THE

BARBARIANS

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

The Battle: A New History of Waterloo

Charlemagne: Father of a Continent

THE DAY OF THE

BARBARIANS

THE BATTLE THAT LED TO

THE FALL OF THE

ROMAN EMPIRE

ALESSANDRO BARBERO

Translated by John Cullen

Copyright 2005 by Alessandro Barbero

Translation copyright 2007 by John Cullen

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information address Walker & Company 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10010.

Published by Walker Publishing Company Inc., New York

Distributed to the trade by Macmillan

All papers used by Walker & Company are natural, recyclable products made from wood grown in well-managed forests. The manufacturing processes conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin.

Map by Ortelius Design, Inc.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA HAS BEEN APPLIED FOR.

Visit Walker & Company's Web site at www.walkerbooks.com

Originally published in Italy in 2005 by Gius. Laterza & Figli as

9 Agostu 378: Il Giorno dei Barbari

First published in the United States by Walker & Company in 2007

This paperback edition published in 2008

eISBN: 978-0-802-71897-6

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Typeset by Westchester Book Group

Printed in the United States of America by Quebecor World Fairfield

CONTENTS

T he subject of this book is a battle that changed the course of world history. It was not a famous fight like Waterloo or Stalingrad; in fact, most people have never heard of it. And yet some believe that it signified nothing less than the end of the ancient world and the beginning of the Middle Ages, because this battle set in motion the chain of events that would lead, nearly a century later, to the fall of the Western Roman Empire. That event is linked to a well-known date that forms part of our common fund of knowledge: AD 476, the year when Romulus Augustulus, the last Roman emperor of the West, was deposed. But in fact the removal of Romulus was only the final, inevitable step in a process that had begun long before. By 476, the emperor was a puppet without any effective power; the empire had already broken up and was losing one piece after another; barbarians were dominant in Gaul, in Spain, in Africa, and even in Italy; and Rome had been sacked more than once, by the Goths in 410 and again by the Vandals in 455. In short, the dissolution of the empire was already so far advanced that the deposition of the last Western emperor was not very important news. A famous essay by Arnaldo Momigliano titled "An Empire's Silent Fall" demonstrates that the so-called great event of 476, the dethronement of Romulus Augustulus, was noted by few at the time.

But if things had reached this point, if the western half of the Roman Empire had been reduced to an empty shell that a barbarian chieftain could sweep aside without eliciting a protest, it was because of a series of traumas that had begun exactly a century before. In 376, an unforeseen flood of refugees at the frontiers of the empire, and the inability of the Roman authorities to manage this emergency properly, gave rise to a dramatic conflict that was to culminate in Rome's most disastrous military defeat since Hannibal's Carthaginians destroyed the Roman army at Cannae in 216 BC.

This book recounts the battle of Adrianople, fought on August 9, 378, in what today is European Turkey and at the time was the Roman province of Thrace. In addition to telling the story of the battle, I shall try to show that it really did mark the end of one era and the beginning of another, an era in which Rome would find it harder and harder to keep the barbarians subjugated by force of arms and to keep believing itself the world's only superpower. I shall talk about the ancient world and the Middle Ages, Romans and barbarians, a multiethnic world and an empire in transformation, and about many other things besides: Christianity, for example, which by this time not only was the official religion of the Roman Empire but was making inroads among the barbarians, too, and changing them. But my central focus will be what happened there, at Adrianople in the eastern Balkans, during the course of a long summer afternoon.

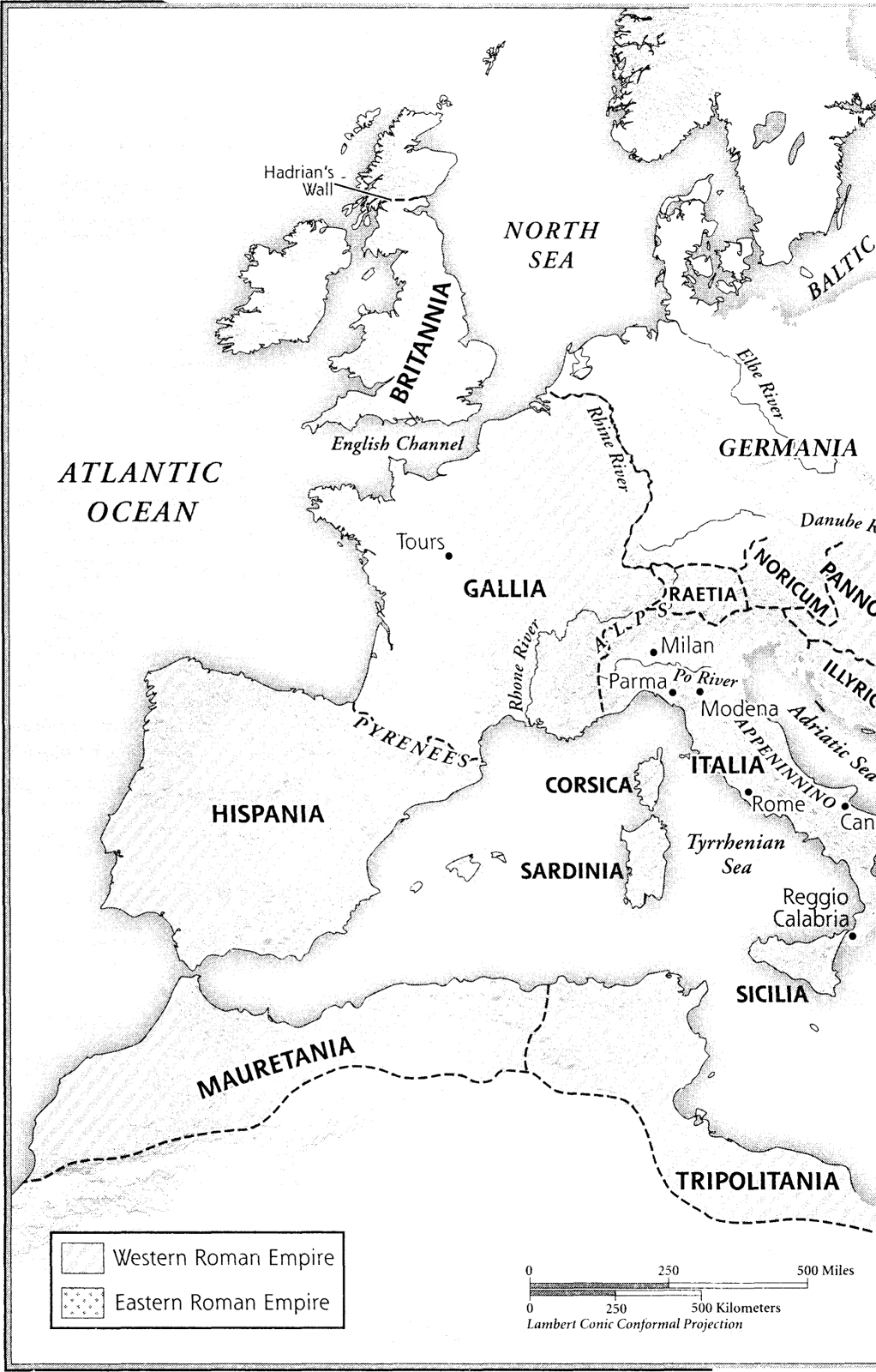

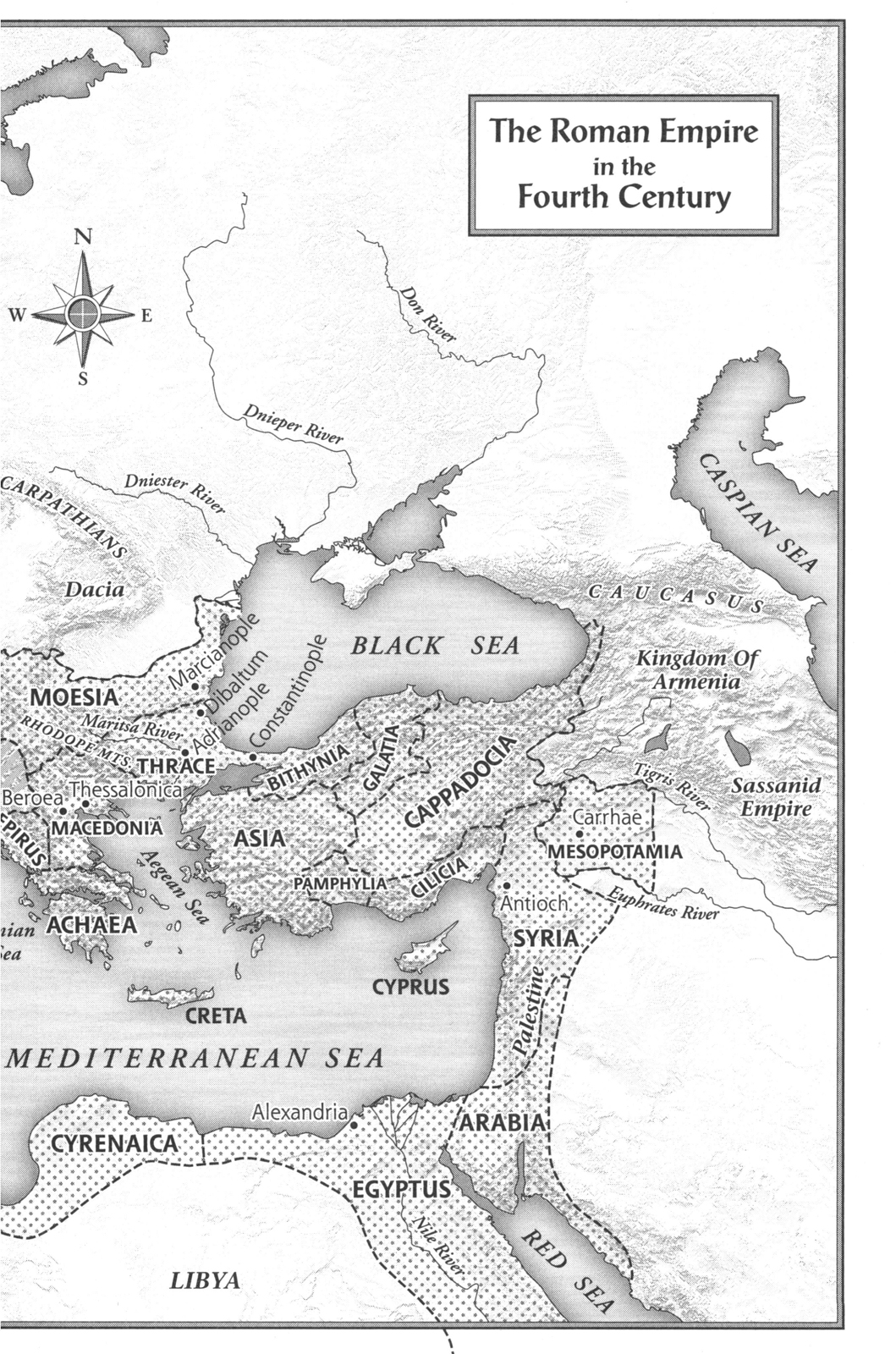

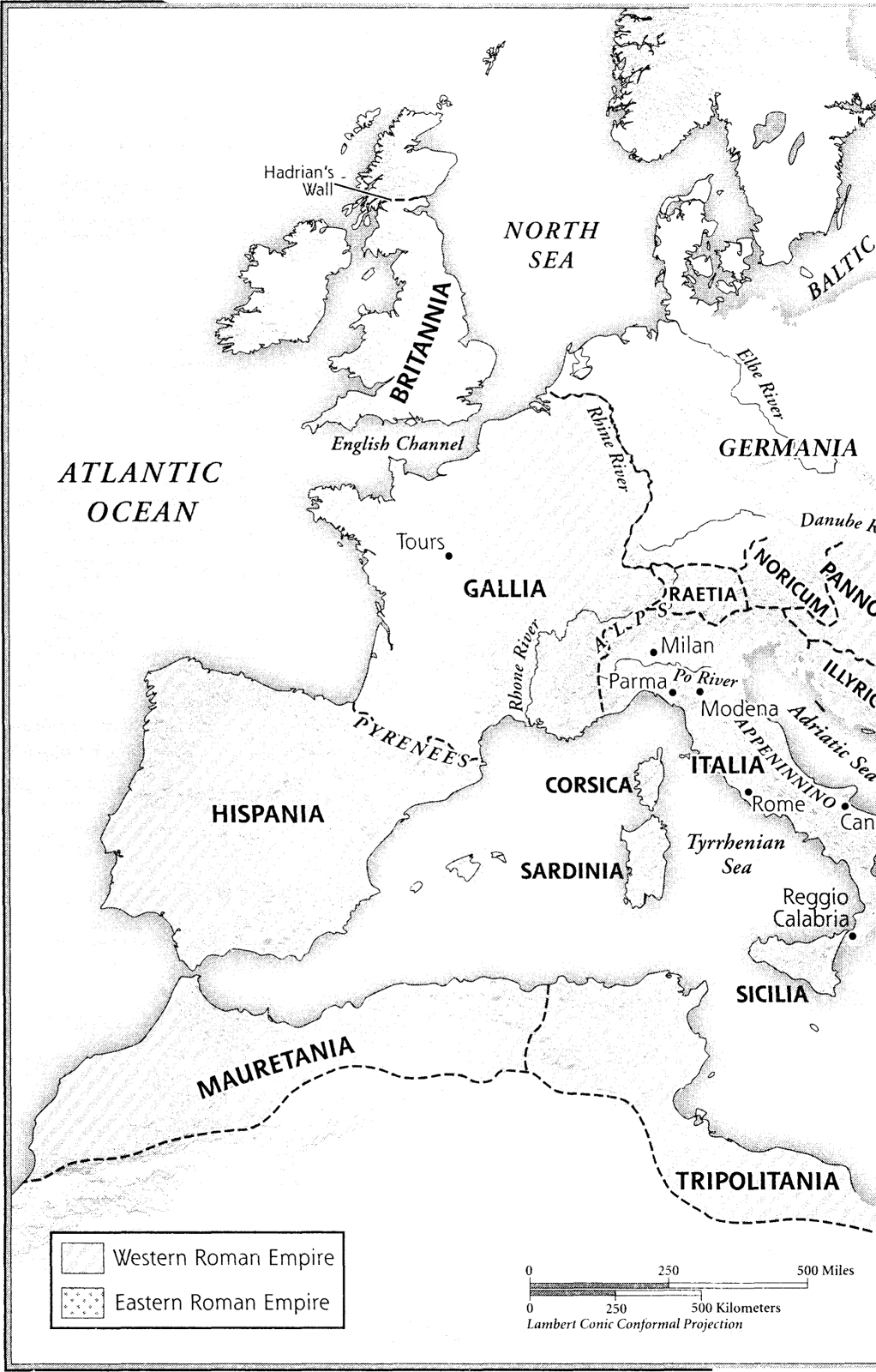

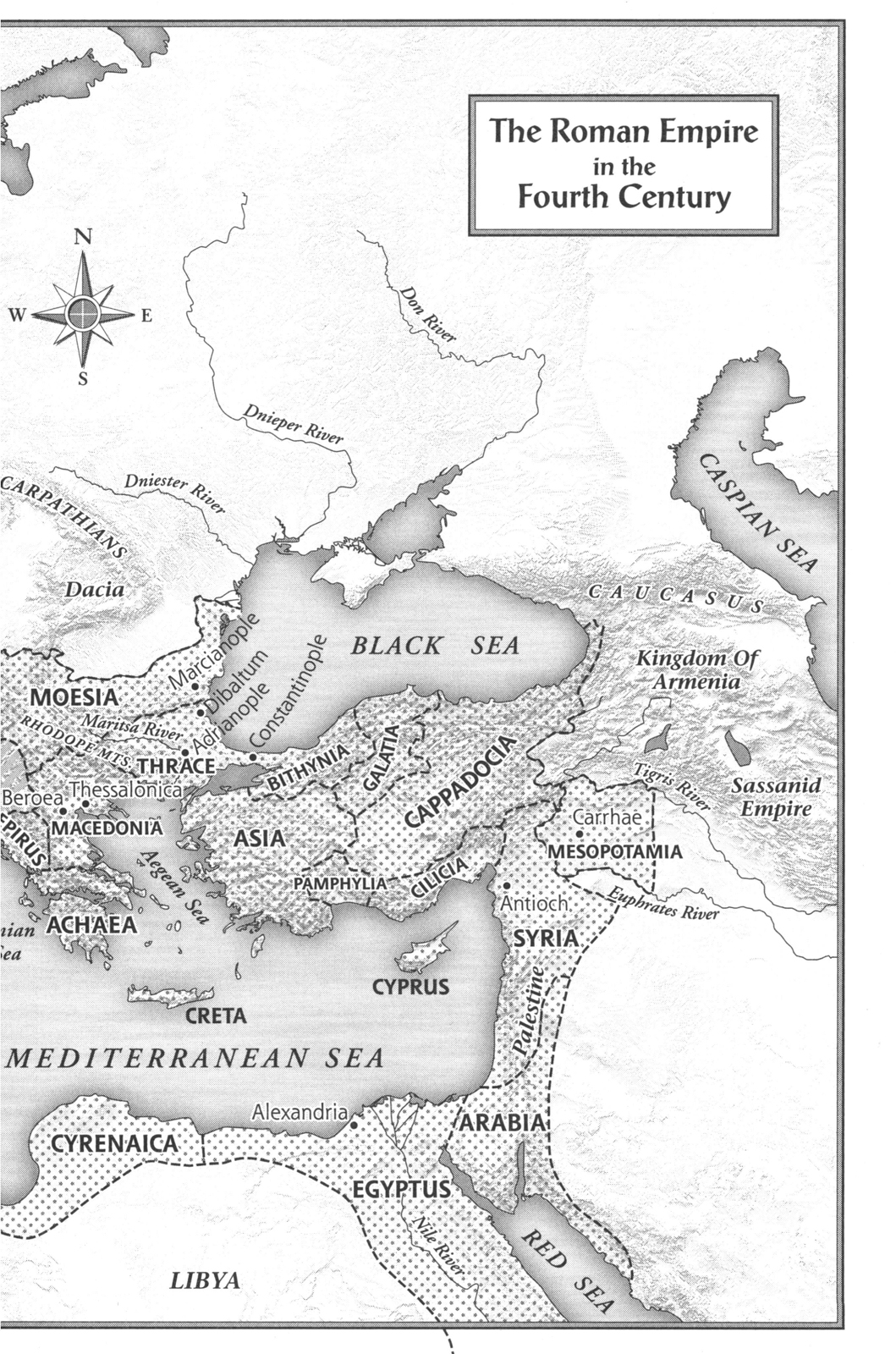

I n the year AD 378, the Roman Empire had grown to immense proportions, with geographic horizons far different from those of contemporary Europe. Today Europe is a continental civilization, open (if at all) toward the Atlantic; the Mediterranean is a boundary, and what lies beyond it is generally perceived as another civilization, another world. The Roman Empire, by contrast, coincided with the Mediterranean basin, and the sea, mare nostrum (our sea), was its center. The boundaries of the empire lay elsewhere: To the north, they were formed by two great rivers, the Rhine and the Danube, that to our way of thinking flow through the heart of Europe but to the Romans were border zones, the outer limits of civilization. Another great river, the Tigris, marked Rome's eastern frontier; the lands it enclosed seem distant and exotic to us, but they were part of the empire, too, and Roman functionaries, soldiers, and merchants probably felt less out of place in Mesopotamia than they did in the frigid outposts of the north. To the south, where the Romans had advanced deep into Africa and Arabia, the boundaries of the empire were the African and Arabian deserts. The Roman presence here was not confined to fortified frontier posts with garrisons of legionaries; it included city-sized commercial centers, great villas, and large estates, with olive groves and vineyards and grain fields. The Mediterranean, the central nervous system of this entire world, was crisscrossed by cargo ships carrying, for example, oil and grain from Tunisia to Rome, a metropolis of one million inhabitants who consumed an enormous quantity of food and provisions.

The lands that constituted the empire thus encompassed much more than the European provinces most familiar to our Western eyes: Spain, long since wrested from Carthage; Gaul, conquered by Julius Caesar; Britain, enveloped in the North Atlantic fog; Italy, which by the time of the battle of Adrianople had lost a portion of its statusand the privileges attendant upon that statusas the imperial center. In addition, the Roman Empire comprised the Balkan provinces, which provided Rome with its best soldiers; Asia Minor, which today we call Turkey; Syria, Palestine, and Egypt, or in other words much of the Middle East, including a portion of the Arabian Peninsula; and, finally, the North African coastal strip now known as the Maghreb. It thus comprised entire regions of the world that Europeans now consider "elsewhere"; yet those regions were at the time an integral part of the Roman world and included the richest and most civilized provinces of the empire.

Civilization's center of gravity was located in the East, and for this reason Emperor Constantine the Great had founded the city of Constantinople in AD 330 as a replacement for Rome. As we know, Constantinople became the modern city of Istanbul, the great Turkish metropolis. In our times, the admission of Turkey into Europe is a matter of controversy, but in the fourth century, Constantinople was the beating heart of the Roman Empire. In this empire, Latin, the language of the Romans, was spoken, but so was Greek; in fact, Greek was spoken more and more, because Greek was the language of the East. Latin was still, everywhere, the language of the courts and the barracks, the language in which laws were written. But in the great cities of the eastern provinces, the same cities where Christianity had known its first diffusion, the dominant language was Greek.

Next page