The project has also benefited from the aid of numerous archives, archivists, collections, and fellow hospital historians. I would like to thank, in particular, Jim Gehrlich, Elizabeth Shepherd, Adele Lerner, and Lisa Mix of the Medical Center Archives of NewYorkPresbyterian/Weill Cornell; Jack Eckert at the Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine of Harvard University, Boston; Arlene Shaner at the New York Academy of Medicine; Miranda Schwartz and Marilyn Kushner at the New York Historical Society; Stephen Greenberg at the National Library of Medicine in Bethesda; Steve Novak of the Archives and Special Collections of the Augustus C. Long Health Sciences Library of Columbia University; Robert Steele, formerly archivist at the Archives Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York City; Kaura Gale and Maria Astifidis of the Beth Israel Hospital; Karen Brewer and Colleen Bradly Sanders at the Ehrman Medical Library, New York University; Rob Roche, archivist at the firm of Shepley Bulfinch, Richardson and Abbott, Boston; and Barbara Opar, Syracuse University Fine Arts Librarian. The outlines of this work began at Cornell University under the able guidance of Christian F. Otto, Mary N. Woods, and Stuart R. Blumin, and I remain thankful for their generous support.

Introduction

To the well-known saying that dirt is only matter in the wrong place, may be added another, that disease, and death itself, is but life in the wrong place.

American Architect and Building News, 1882

Hospital: An institution or establishment for the care of the sick or wounded, or of those who require medical treatment.

Oxford English Dictionary

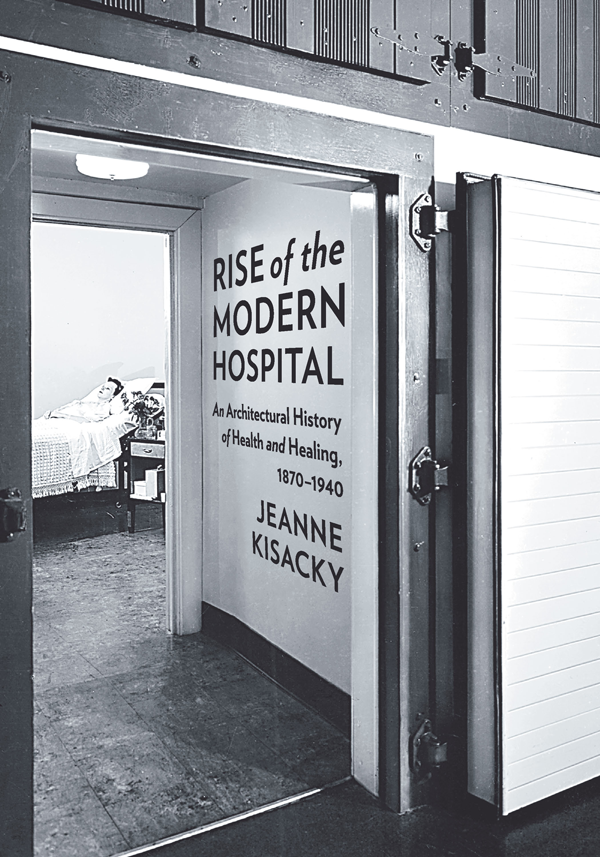

That a hospitalas an institution providing care to sick and injured personsshould be designed to promote the health of its inhabitants is a foregone conclusion. How, exactly, a building design might be expected to facilitate cure or suppress illness is more elusive, and it is the focus of this book.

From the mid-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century, American hospital designers experimented with a number of competing strategies for the role the building design was to play in the health of its occupants. Designers debated whether the hospital building was a therapy in itself, providing a surrounding that would somehow keep persons in close proximity from sharing their ailments and perhaps even actively instill greater health in its occupants, or whether it was a tool that would organize the activities, materials, and events within the building into an efficient, controlled, therapeutic process.

Over time the questions and the preferred answers changed, reflecting altered medical, social, urban, and architectural circumstances. Mid-nineteenth-century hospital designers overwhelmingly privileged the buildings therapeutic potential over its ability to facilitate medical treatments. Mid-twentieth-century hospital designers overwhelmingly privileged the buildings potential to facilitate medical actions and interactions over its intrinsic healthiness. This shift from considering the hospital as a therapy to considering it as a tool accompanied drastic institutional transformations. From the last resort of the impoverished urban unwell, hospitals became the first resort of all classes of ailing citizens. From neutral containers of general care, they became active locations in the development of specialized scientific medicine. From charitable institutions organized on

Architectural decisions also influenced these transformations. Where a hospital was located in relation to the city, to other hospitals, and to specific neighborhoods affected its patient load and characteristics as directly as the composition of its medical staff. What facilities a hospital contained and how they were arranged could turn it from a warehouse for the sick poor into a location for cutting-edge medicine attracting all classes. The sizes of its inpatient roomswhether wards (large rooms that housed a number of patients) or single-patient roomsdetermined the number of people that could be treated and the extent to which each patient could be isolated from the others, and even delineated who paid for care.

These transformations are relevant today as designers struggle to develop new hospital buildings that are efficient and attractive, and decide which buildings from earlier time periods are worth saving and which are destined only for demolition. The truth is, however, that we know very little in detail about how and why American hospitals shifted from pavilions to high-rises in the crucial period between the end of the Civil War and the beginning of World War II.

Works that do cover the decades between the 1870s and 1940s often do so in a few pages (or even just a few paragraphs), and touch on the same sequence of examples, moving directly from the internationally famous pavilions of the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore (18751885) to the mature high-rises of the 1930s such as the Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center in New York City by James Gamble Rogers (1929), the New York HospitalCornell Medical Center in New York City by Coolidge Shepley Bulfinch and Abbott (1932), or the Beaujon Hospital in Clichy, France, by Jean Walter (1935). In between these two extremes are given at best a handful of intermediate examples, such as Albert J. Ochsners 1905 call for vertical hospital design, Arnold Brunners collaboration with S. S. Goldwater on the new Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City (1901), Goldwaters ideal ward design for cities (1910), or William Henmans Royal Victoria Hospital in Belfast (1903). The detailed sequence of transformation of hospital design between the 1870s and 1930s has become so lost to history that in 1976 Peter Stone could confidently (if erroneously) state that there had been

A few recent works have begun to fill this gap, but each still reveals only a small piece of a much larger story. Jeremy Taylor examines hospital design up to 1914, but he focuses on the transformation of the pavilion-ward type in Britain, not on the development of high-rise, centralized, modern hospital structures. Sven-Olov Wallenstein presents a number of hospitals between the 1900s to the 1930s, but his examples are mostly sanatoria (a specialized type of hospital with design requirements that reduced their height and their centralization) and are chosen for their modernist design and designers rather than for their representation as epitomes of hospital planning and function. David Charles Sloane and Beverlie Conant Sloane correlate shifts in the practices and experiences of patients, doctors, and benefactors to the architectural shifts of hospitals from a home to a medical workshop to a vertical hospital, but only as a brief prelude to an extended discussion of the transformations of the last half of the twentieth century. In numerous publications, Annmarie Adams has focused on hospital design in the decades between the 1900s and 1940s, but in order to understand hospital buildings as artifacts of material culture she has structured her work as a series of thematic essays rather than a chronology of hospital design. This approach, which studies buildings as historical records in and of themselves, has allowed her to develop a deep knowledge of the social, cultural, and political issues enmeshed in a few hospital designs, but not a broad overview of hospital design in these transitional decades. Her focus on works by hospital architect Edward F. Stevens also limits the story she tells. Stevens was an influential and gifted designer who worked on hospital projects across the globe, but his body of work remained consistently low-rise in comparison to other contemporary practitioners like York and Sawyer or James Gamble Rogers, who pioneered in high-rise hospital designs.