Penguin Monarchs

THE HOUSES OF WESSEX AND DENMARK

| Athelstan | Tom Holland |

| Aethelred the Unready | Richard Abels |

| Cnut | Ryan Lavelle |

| Edward the Confessor | James Campbell |

THE HOUSES OF NORMANDY, BLOIS AND ANJOU

| William I | Marc Morris |

| William II | John Gillingham |

| Henry I | Edmund King |

| Stephen | Carl Watkins |

| Henry II | Richard Barber |

| Richard I | Thomas Asbridge |

| John | Nicholas Vincent |

THE HOUSE OF PLANTAGENET

| Henry III | Stephen Church |

| Edward I | Andy King |

| Edward II | Christopher Given-Wilson |

| Edward III | Jonathan Sumption |

| Richard II | Laura Ashe |

THE HOUSES OF LANCASTER AND YORK

| Henry IV | Catherine Nall |

| Henry V | Anne Curry |

| Henry VI | James Ross |

| Edward IV | A. J. Pollard |

| Edward V | Thomas Penn |

| Richard III | Rosemary Horrox |

THE HOUSE OF TUDOR

| Henry VII | Sean Cunningham |

| Henry VIII | John Guy |

| Edward VI | Stephen Alford |

| Mary I | John Edwards |

| Elizabeth I | Helen Castor |

THE HOUSE OF STUART

| James I | Thomas Cogswell |

| Charles I | Mark Kishlansky |

| [ Cromwell | David Horspool ] |

| Charles II | Clare Jackson |

| James II | David Womersley |

| William III & Mary II | Jonathan Keates |

| Anne | Richard Hewlings |

THE HOUSE OF HANOVER

| George I | Tim Blanning |

| George II | Norman Davies |

| George III | Amanda Foreman |

| George IV | Stella Tillyard |

| William IV | Roger Knight |

| Victoria | Jane Ridley |

THE HOUSES OF SAXE-COBURG & GOTHA AND WINDSOR

| Edward VII | Richard Davenport-Hines |

| George V | David Cannadine |

| Edward VIII | Piers Brendon |

| George VI | Philip Ziegler |

| Elizabeth II | Douglas Hurd |

Andy King

EDWARD I

A New King Arthur?

ALLEN LANE

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published 2016

Copyright Andy King, 2016

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Cover design by Pentagram

ISBN: 978-0-141-97878-9

To Claire, my Clio

Preface

If ever there was a national hero, it was Edward of England. So wrote Edward Jenks in his hagiography of Edward I, published in the Heroes of the Nations series in 1902. Today, however, the king is perhaps best known as the cold-hearted, ruthless, warmongering tyrant (and defenestrator of Piers Gaveston) portrayed by Patrick McGooghan in that epic Hollywood fantasy Braveheart (1995).

It has become a clich for the authors of books about medieval kings to start by pointing out that it is scarcely possible to write a biography of their subject, in the modern sense of the genre. Clichd it may be, but largely true, for there is scant evidence to shed light on the private motivations behind a kings public deeds. Indeed, it is not always possible to distinguish between what was done by the king himself, what was done at the kings direct order, and what was done by his officials acting in his name (possibly without his knowledge). Even the kings own words were frequently written up after the event by royal officials with only general reference to what he actually said, or were entirely invented by imaginative chroniclers, who set out to provide a moral or poetic rather than a strictly historical truth. But if Edward himself remains something of an enigma, we know a great deal about his reign. At this time, England was perhaps the most bureaucratic government in Western Christendom; vast quantities of its records, set down on acres of dried sheepskin, are still preserved at The National Archives. And notwithstanding their literary flourishes, most of the chronicle accounts are, in fact, very well informed.

Edward remains one of Englands more controversial kings, but he was very much a prince of his time, ruling in accordance with contemporary moral and political precepts. Undoubtedly a covetous and ruthless man, he nevertheless acted according to his lights; this book attempts to explain those lights.

Note on the Text

Money

Medieval England had a currency based on the Carolingian French denominations of pounds, shillings and pence. Most coinage was minted as silver pennies.

1 pound () = 20 shillings (s) = 240 pennies (d)

1s = 12d

The mark, used as a unit of account, equalled two-thirds of a pound

1 mark = 13s 4d

It is difficult to make meaningful comparisons with modern prices, but at this time 5 was considered a reasonable annual salary for a clerk; those with an annual income of 40 were considered sufficiently wealthy that they ought to take up knighthood; and an annual income of 1,000 was considered sufficient to maintain the estate of an earl. In the late thirteenth century, Englands total money supply was perhaps not much more than 1 million. The crowns ordinary annual income was 26,828 3s 9d, according to a somewhat spuriously precise Exchequer estimate of 1284.

Gascony and Aquitaine

Gascony is a region of south-west France centred on Bordeaux. From 1154 until 1450, the kings of England ruled Gascony as dukes of Aquitaine. Technically, Gascony was a lordship within the larger duchy of Aquitaine, but in practice the English referred to Gascony and Aquitaine interchangeably.

Prologue

A European King

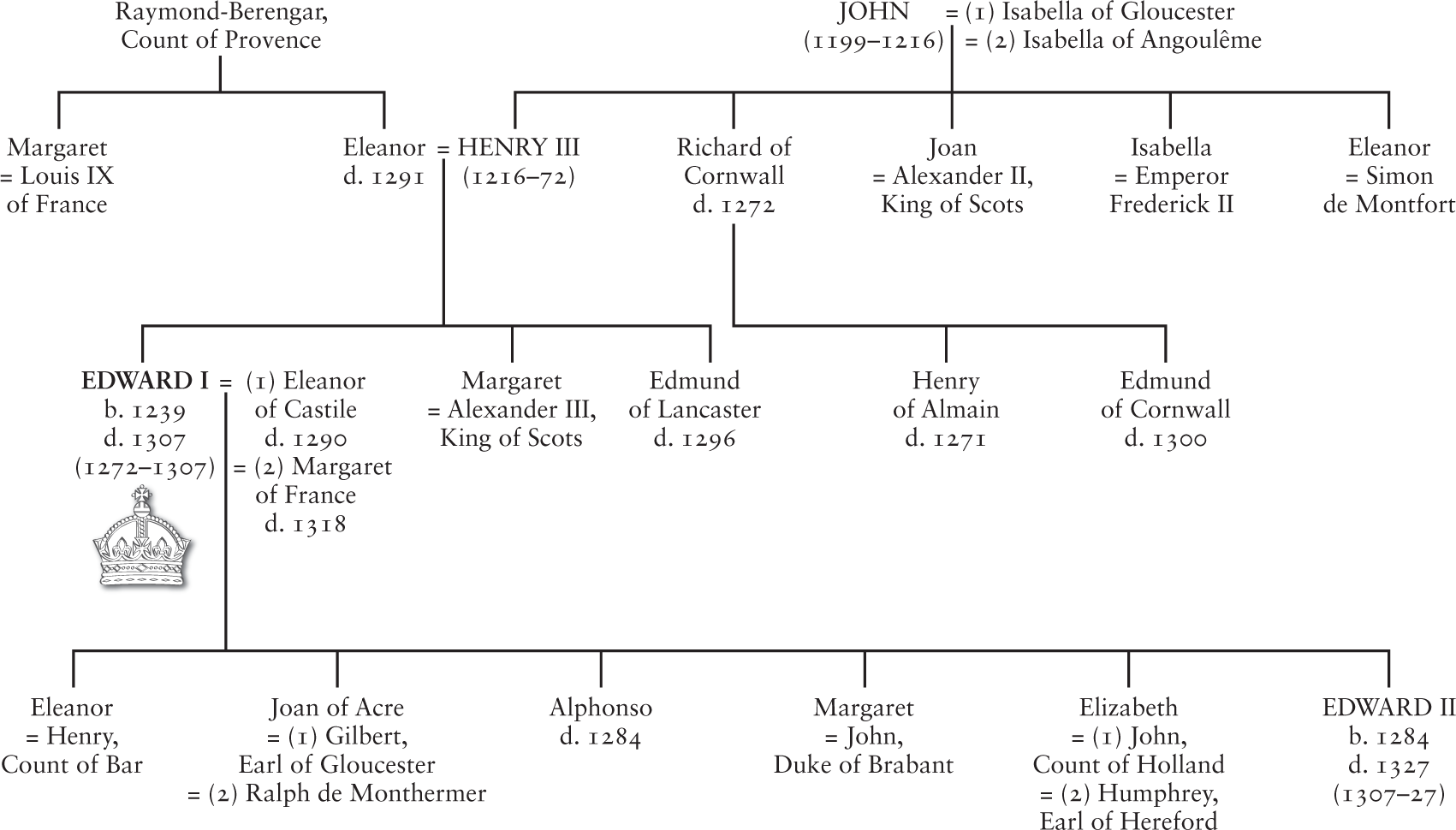

On the night of 17 June 1239, Eleanor, Queen of England, gave birth to a son. Eleanors father was the Count of Provence. The babys father, Henry III, was the great-grandson of the Frenchman Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou (who, legend had it, was descended from the Devil). Henry was also Duke of Aquitaine, by right of which title he ruled Gascony, a region of south-west France which stretched from Bordeaux to the Spanish border. He would also have been Duke of Normandy had not his father, King John, lost the duchy in 1205.

His continental ancestry notwithstanding, the boy would become the first King of England since the Conquest to bear an English name. He was named after Edward the Confessor (who died in 1066, and was canonized in 1161). The pious Henry III had a particular reverence for English saints; Edwards younger brother was named Edmund, after the martyred king of the East Angles (d. 869). But these were not just English saints; they were