Stephen Alford

EDWARD VI

The Last Boy King

Contents

Penguin Monarchs

THE HOUSES OF WESSEX AND DENMARK

| Athelstan | Tom Holland |

| Aethelred the Unready | Richard Abels |

| Cnut | Ryan Lavelle |

| Edward the Confessor | James Campbell |

THE HOUSES OF NORMANDY, BLOIS AND ANJOU

| William I | Marc Morris |

| William II | John Gillingham |

| Henry I | Edmund King |

| Stephen | Carl Watkins |

| Henry II | Richard Barber |

| Richard I | Thomas Asbridge |

| John | Nicholas Vincent |

THE HOUSE OF PLANTAGENET

| Henry III | Stephen Church |

| Edward I | Andy King |

| Edward II | Christopher Given-Wilson |

| Edward III | Jonathan Sumption |

| Richard II | Laura Ashe |

THE HOUSES OF LANCASTER AND YORK

| Henry IV | Catherine Nall |

| Henry V | Anne Curry |

| Henry VI | James Ross |

| Edward IV | A. J. Pollard |

| Edward V | Thomas Penn |

| Richard III | Rosemary Horrox |

THE HOUSE OF TUDOR

| Henry VII | Sean Cunningham |

| Henry VIII | John Guy |

| Edward VI | Stephen Alford |

| Mary I | John Edwards |

| Elizabeth I | Helen Castor |

THE HOUSE OF STUART

| James I | Thomas Cogswell |

| Charles I | Mark Kishlansky |

| [ Cromwell | David Horspool] |

| Charles II | Clare Jackson |

| James II | David Womersley |

| William III & Mary II | Jonathan Keates |

| Anne | Richard Hewlings |

THE HOUSE OF HANOVER

| George I | Tim Blanning |

| George II | Norman Davies |

| George III | Amanda Foreman |

| George IV | Stella Tillyard |

| William IV | Roger Knight |

| Victoria | Jane Ridley |

THE HOUSES OF SAXE-COBURG & GOTHA AND WINDSOR

| Edward VII | Richard Davenport-Hines |

| George V | David Cannadine |

| Edward VIII | Piers Brendon |

| George VI | Philip Ziegler |

| Elizabeth II | Douglas Hurd |

For Matilda

Prologue

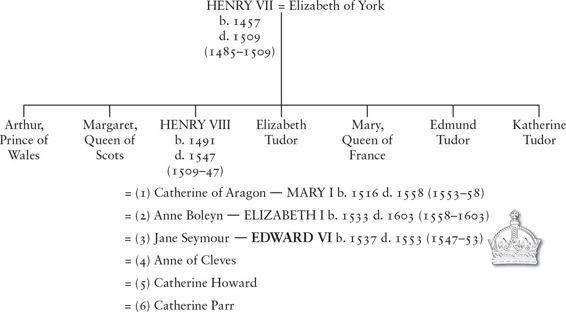

On a winters day in 1547 a young boy was given the news that his father was dead. This boy was a prince, Edward, Duke of Cornwall, the son and heir of Henry VIII. He was nine years old.

There is a kind of memory that seems to imprint itself so clearly upon the mind that for the rest of our lives we feel we are able always to recover it; it is preserved as it was for ever. Was it like this for Edward? The words were spoken by his uncle Edward Seymour, Earl of Hertford. It was 30 January, a Sunday, and they were at Enfield Manor in Middlesex. With the new king was the younger of his two sisters, thirteen-year-old Princess Elizabeth.

The Earl of Hertford declared to him and his younger sister Elizabeth the death of their father. This was the only record Edward made of the interview. His words read like a public notice: just seventeen of them, spare, factual, revealing no emotion, written almost from the outside of a life looking in.

Elizabeth and Hertford would have made their obedience to Edward; very probably they kissed his hand. He was no longer only a brother or a nephew but a king sent by God to rule them. Did Edward and Elizabeth cry? Edwards earliest biographer said that they did, but on no evidence. Perhaps it felt to them like a nursery game, where children imagine for themselves different and altered lives. But Edward and Elizabeth were Henry VIIIs children: one day their father would die and their lives would then change for ever; it was a future from which they had no escape.

Probably the interview felt just as unreal for the Earl of Hertford. For a night he had walked the galleries of Whitehall Palace waiting for King Henry to die. A little time later, in the very early hours of Saturday 29 January, he took his horse for the night ride to Hertford Castle. He and Sir Anthony Browne, Henrys Master of the Horse, were there before three oclock in the morning. The earl had forgotten to leave the key to recover Henrys will with the kings secretary, Sir William Paget, and so hurriedly he wrote instructions for what Paget, his fixer at Whitehall, should do with it.

As yet Henrys death was a secret even to Edward. It was only once Edward had been escorted by Hertford and Browne to Enfield Manor that Hertford broke the news to his nephew. Late at night on 30 January he wrote to the dead kings council in London, revealing through his pen a telling slip of the unconscious. Hertford referred to Henry as the late king who we doubt to be in heaven; he quickly corrected himself to write who we doubt not to be in heaven. Henry VIII was gone: thirty-eight years of magisterial and at times unnerving kingly power were over.

For the Earl of Hertford there was a new king to put on the throne and his own pre-eminence in that kings government to secure. Edward had to be taken to London. Hertfords plan was for his nephew and monarch to be on horseback by eleven oclock on the morning of 31 January and at the Tower of London by three oclock that same afternoon.

As Edward and his entourage were setting off from Enfield, the formal proclamation of his accession as king was already being read out in Westminster Hall:

Edward VI, by the grace of God King of England, France, and Ireland, defender of the faith and of the Church of England and also of Ireland in earth the supreme head, to all our most loving, faithful, and obedient subjects, and to every of them, greeting.

Where it hath pleased Almighty God, on Friday last past in the morning to call unto his infinite mercy the most excellent high and mighty prince, King Henry VIII of most noble and famous memory, our most dear and entirely beloved father, whose soul God pardon; forasmuch as we, being his only son and undoubted heir, now invested and established in the crown imperial of this realm, and other his realms, dominions, and countries, with all regalities, pre-eminences, styles, names, titles, and dignities to the same belonging or in any wise appertaining

Few would have remembered the last time a monarch was proclaimed to his people. That had been in 1509 when a callow and inexperienced king two months away from his eighteenth birthday had been the great hope for change after the tough rule of his father, Henry VII.

So Tudor England once again had a new king who ruled by blood, by the law of rightful succession and by Gods will. Touched by the divine, he was the protector and judge of his people, as well as the Supreme Head on earth of the English Church his father had made out of the convulsions of schism with Rome. And, as no one could have failed to notice, he also just happened to be a boy.