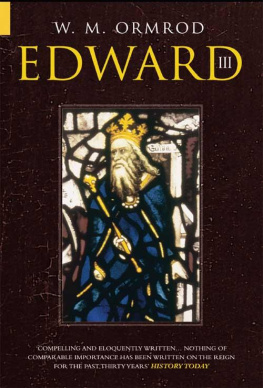

EDWARD III

W.M. Ormrod

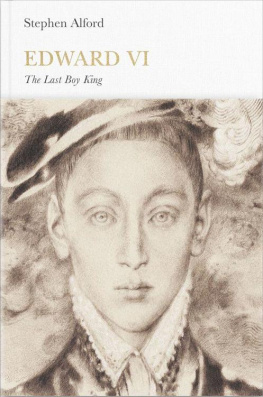

Cover Illustration:

Edward III, from the east window of York Minster.

Dean and Chapter of York 2005

First published in 1990

This edition published in 2005

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL 5 2 QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2011

All rights reserved

W.M. Ormrod, 1990, 2000, 2005, 2011

The right of W.M. Ormrod, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 6893 8

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 6894 5

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

About the Author

Mark Ormrod is Professor of Medieval History at the University of York. He is widely regarded as the world expert on Edward III. His other books include The Kings & Queens of England (Of the numerous books on the kings and queens of England, this is the best Alison Weir), Political Life in Medieval England, The Evolution of English Justice (co-author), The Black Death in England (co-editor), Time in the Medieval World (co-editor), and The Problem of Labour in Fourteenth Century England (co-editor). He lives in York.

Preface

This book was first published in 1990; the text as set out here is the same as that found in the 1990 edition and its 1993 paperback version (with minor corrections and stylistic changes), but the book has been redesigned and includes many new illustrations. I am grateful to Jonathan Reeve of Tempus for offering me the opportunity to reissue the work, and to Kate Adams and Anne Phipps for their assistance.

The 1990s was a fruitful decade for Edward III studies and much new material has become available for the study of the reign. That work, and my own continued interest in the subject, has led me to recast some of my thoughts on both the achievements and the shortcomings of the Edwardian regime: were I writing this book in 1999, it would undoubtedly be different. However, I also hold firm to my original thesis that the long period of domestic political stability during the middle decades of the fourteenth century cannot be accounted for merely in terms of successful foreign war and can only satisfactorily be explained by examining the nature and achievements of Edwards government in England. While recent work (including my own) has tended to place much greater stress on the theme of justice than is evident in this study, I nevertheless remain convinced that the fiscal accomplishments of the mid-fourteenth century also represent the outcome of sound political management and effective administrative control.

There is still no definitive modern biography of Edward III: in spite of (or rather, perhaps, because of) the recent spate of specialised studies of the reign, it seems that the task becomes more, rather than less, challenging with the passing of time. This is inevitably a somewhat unmanageable reign, too long, too disparate, too eventful (as it were) for its own good. To write it from the perspective of 1327 is to acknowledge Edward IIIs extraordinary transformation of a monarchy brought low by the personal and political ineptitude of his father into one of the most respected regimes in fourteenth-century Europe; yet to write it from the vantage point of 1377 is to emphasise the defects and weaknesses of the regime exposed to bitter public criticism in the Good Parliament and the Peasants Revolt. Above all, perhaps, Edward himself remains an enigma. Lacking the vividness of contemporary sources that open windows on the characters of a Henry II, a Henry V or a Henry VIII, we are left with mere fragments and constructions that are strong on the kings attitude to fighting, less certain on his commitment to culture, decidedly shadowy on his personal vision of governance. It may be that new techniques in textual analysis may yet fill some of the holes in our understanding. In the meantime, however, the subject (both human and thematic) remains an abiding interest precisely because it is so uncertain and so fluid.

I have never liked the notion of intellectual monopolisation that lies behind the claim that Edward III is my king; rather, I offer this book as representing something of my personal interpretation of that king and of his reign. It is in the contrasts that emerge between this and other, less sympathetic, studies that we will begin to find if not the definitive Edward III then at least a new, more vivid and more dynamic picture of political life in fourteenth-century England.

Mark Ormrod

November 1999

Introduction

the Lord Edward, lately king of England, of his good will, and by the common counsel and consent of the prelates, earls, and barons, and other nobles, and all the community of the realm, has given up the government of the realm, and has granted and wishes that the government of the said realm should fall upon the Lord Edward, his eldest son and heir, and that he should reign and be crowned king

It was in these words, proclaimed in public places throughout the realm, that most of the inhabitants of England heard of the change of ruler effected in the winter of 13267. Few knew the details or understood the implications of this event. The abdication, or deposition, of Edward II was arranged by Queen Isabella and her lover Roger Mortimer during an extraordinary parliament held at Westminster in January 1327. The prelates and peers, knights and burgesses present at this meeting were closely in touch with events, as were some of the citizens of London, who put strong pressure on the assembly to deliver the realm from the ineptitude of the king. The people who knew most of all were the members of the deputation sent to Edward at Kenilworth to present the demands of his subjects that he renounce his title. Some of those who attended this meeting later told their stories, and the events were reported in the chronicles. It is doubtful, however, whether many were interested in the theoretical significance of the revolution which had taken place. Within the limits of legal memory no king had been deprived of his authority in this way. Edward II had simply lost the right to rule by his own blatant incapacity, and by allowing his henchmen the Despensers to exercise a quite arbitrary authority during the last years of his reign. Somehow (and the details are by no means clear) a satisfactory compromise was reached, by which the king was held to have given up the throne freely and to have bestowed it on his eldest son. Events in 13267 could therefore be conveniently interpreted as a simple speeding up of the natural succession. Those who best understood what had happened at Westminster and Kenilworth were precisely those in whose interests it was to draw a discreet veil over the proceedings. The majority of the new kings subjects in the provinces were in any case more than content to know that a highly unpopular ruler had been removed, and to hope for better things from his successor.

Fifty years later, when Edward III died, the image of the monarchy was very different. Edward was to be remembered as a victorious and honourable king who had won respect abroad and popularity at home. A poem written several years after his death presented him as the minister of God, a scourge to his enemies, and a kind and just ruler to his people: one who indeed deserved the society of the angels. At the end of the fourteenth century the St Albans chronicler Thomas Walsingham wrote thus: