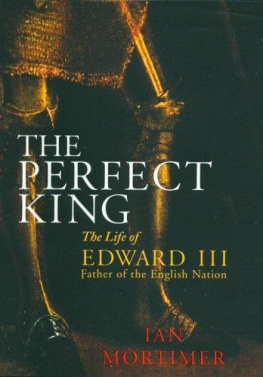

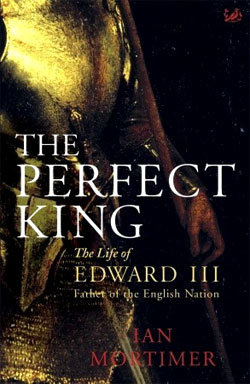

Edward III:

The Perfect King

Ian Mortimer

Copyright

Edward III: The Perfect King

Copyright 2006, 2014 by Ian Mortimer

Cover art, special contents, and Electronic Edition 2014 by RosettaBooks LLC

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Cover jacket design by Carly Schnur

ISBN e-Pub edition: 9780795335464

This book is dedicated to my wife, Sophie, who has been so supportive during the months of frustration, stress, worry and euphoria which inevitably occur when trying to encapsulate a life as rich and complicated as Edward IIIs. She has sat outside the walls of Calais, as it were, and watched Sir Walter Manny take on whole armies armed only with a tooth-pick. The completion of this book is something in which she too can take pride.

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

17 Edward the Gracious

8 The Descendants of Edward III

Full titles of works appearing in the notes

ILLUSTRATIONS

AUTHORS NOTE

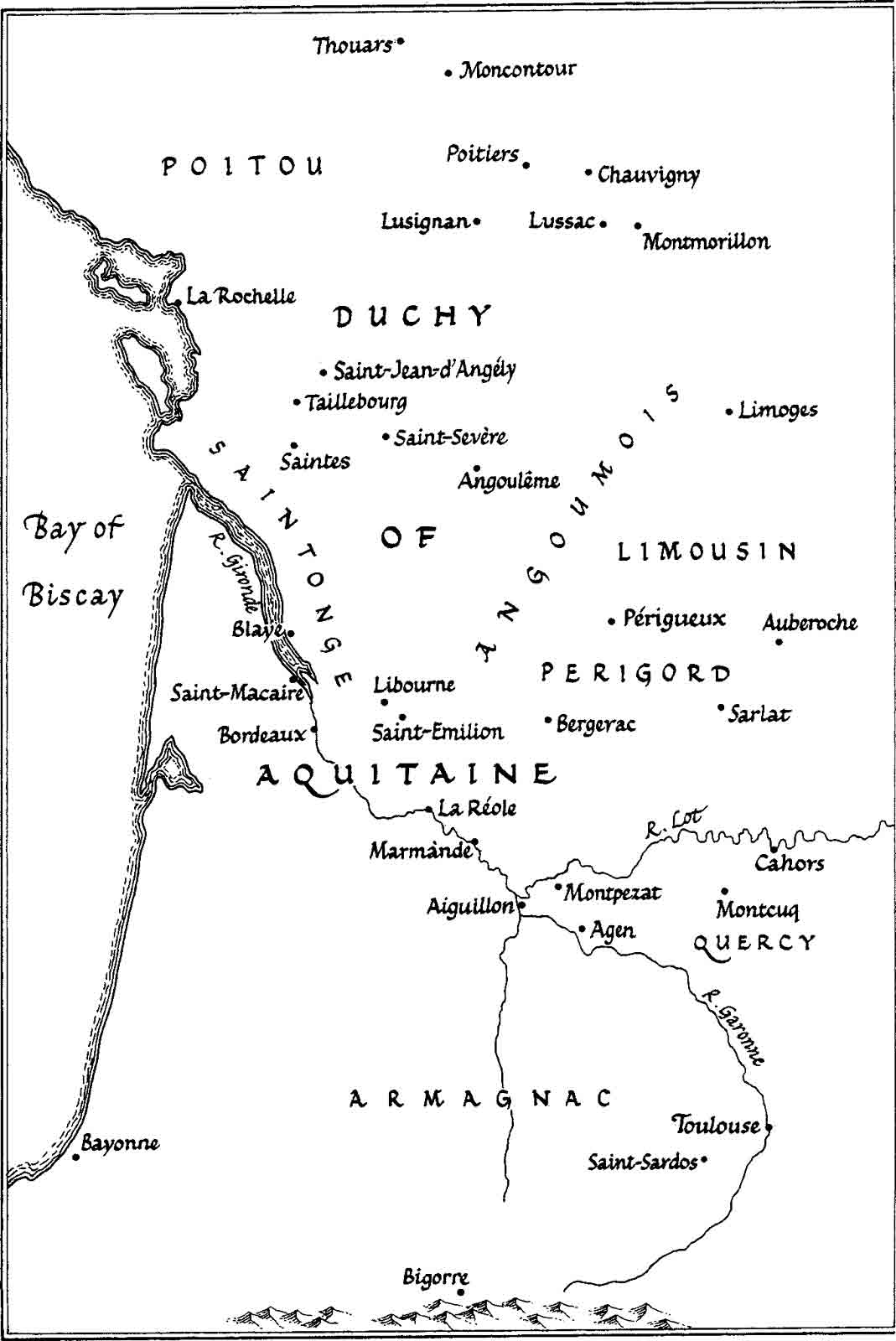

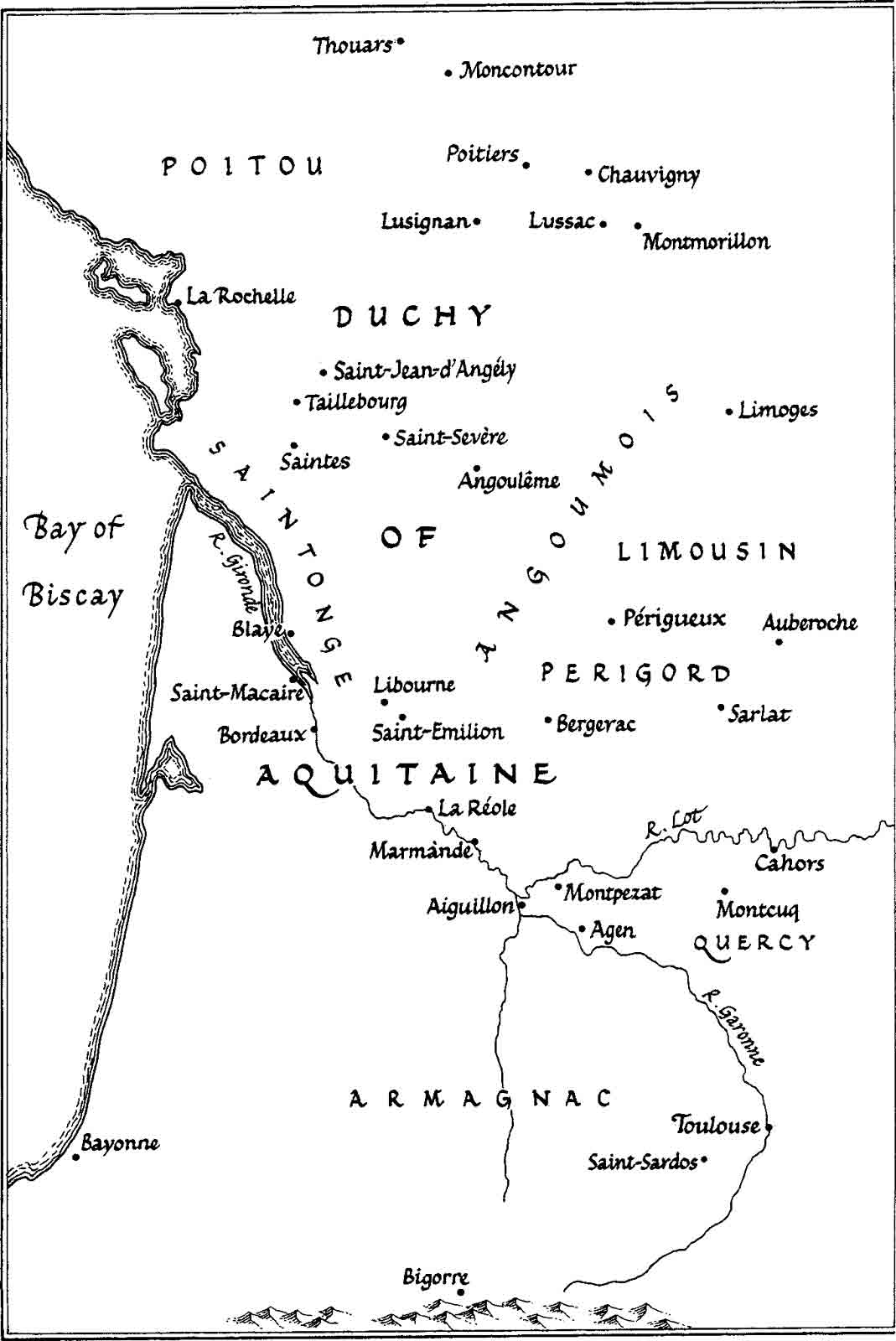

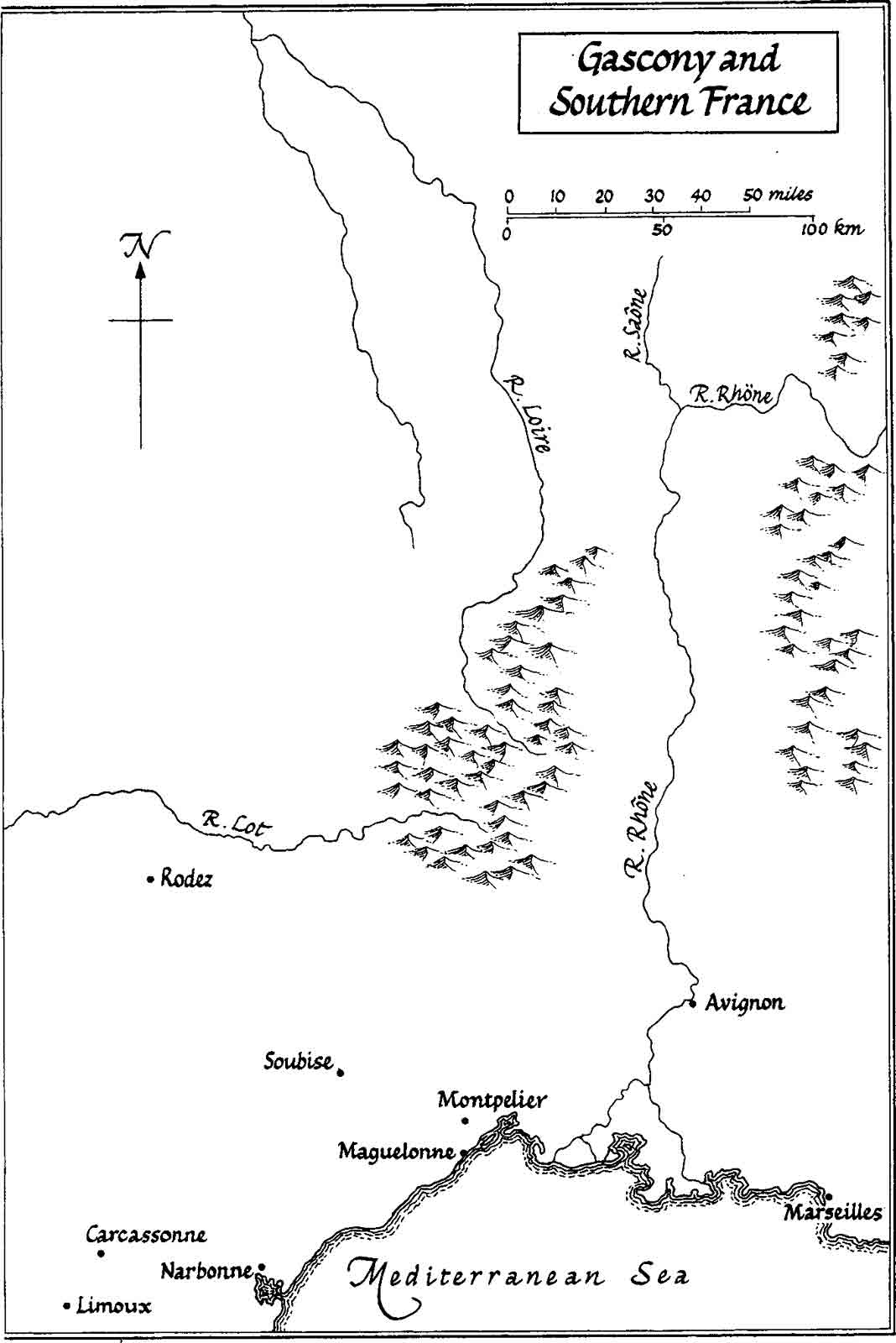

This book deliberately employs the ambiguous use of the term Gascony to describe the English-ruled territory in the south-west of France, in keeping with most books on the fourteenth century. The duchy of Aquitaineas inherited from Eleanor of Aquitainewas far more extensive than Gascony but there were times when English authority was squeezed and the two were practically synonymous. It would be convenient to use just the one word to describe the duchy and its extensions, and there is oneGuiennebut it is very rarely used, even by scholars, and would look very odd in a biography. So, in order to avoid the awkward adjective Aquitainian and the even more awkward Guiennese, two terms have been used: Aquitaine for the title of the duchy and (later) principality, and Gascony and Gascon when referring to the region generally.

Most English surnames which include de in the original source have been simplified, with the silent loss of the de. Where it remained traditionally incorporated in the surname (e.g. de la Pole, de la Beche, de la Ware) these have been retained. De has generally been retained in French names (e.g. de Harcourt, de Montfort, de Blois). With Italian names, de has normally been retained (e.g. del Caretto, de Controne, de Sarzana) but where it is customary not to keep it (e.g. Fieschi, Forzetti) it has been dropped.

With regard to international currency, the gold florin fluctuated greatly over the period covered by this book. According to the Handbook of Medieval Exchange, it was worth as little as 2s 8d in 1346 and as much as 4s in 1332 and 1338. It was also worth different amounts in different places at the same time, and could even be worth different amounts in the same place at the same time. Very roughly speaking, one florin was usually worth slightly more than 3s prior to 1340 and slightly less than 3s thereafter. Many other writers use the rate of 1 florin = 3s 4d, as this allows the easy conversion of 6 florins = 1. In this book this rate is used up to 1340 and the slightly more accurate rate of 1 florin = 3s is used after that year, which implies a conversion of 6.67 florins = 1. The other unit of international accounting used in this book, the mark, was a constant 13s 4d.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

It is impossible to write a book like this without incurring a number of debts of gratitude. I hope that readers will not begrudge me here mentioning the names of my agent, James Gill, and my editors, Will Sulkin and Jrg Hensgen. I am also very grateful to two scholars for their assistance: Dr Paul Dryburgh, who surveyed many of the wardrobe accounts for me in the research stages, and Professor Mark Ormrod of the University of York, who provided me with many valuable hints, photocopies, offprints and references when the book was in a draft form. I would also like to thank staff at the National Archives, the British Library, Exeter University Library, Gloucestershire Record Office, the National Portrait Gallery Archive, Warwickshire County Record Office and Westminster Abbey Library. I am grateful to all those who provided me with accommodation when undertaking research, namely: Zak Reddan and Mary Fawcett, Jay Hammond, Robert and Julie Mortimer, Susannah Davis and Anya Francis. I acknowledge the support of the K Blundell Trust, administered by the Society of Authors, who gave me a grant in the course of writing this book. Finally, I want to say a huge thank you to my familySophie, especially, but also Alexander, Elizabeth, and Oliverfor keeping me going.

Ian Mortimer

Moretonhampstead

May 2005

He who loves peace, let him prepare for war.

Flavius Vegetius Renatus, writer on warfare (c. 375)

According to the Theory of War, which teaches that the best way to avoid the inconvenience of war is to pursue it away from your own country, it is more sensible for us to fight our notorious enemy in his own realm, with the joint power of our allies, than it is to wait for him at our own doors.

King Edward III (1339)

When you dont fight, you lose.

Leszek Miller, Prime Minister of Poland (2003)