She-Wolf of France, with unrelenting fangs, that tearst at the bowels of thy mangled mate

Thomas Gray

It is not wise to set yourself in opposition to the King. The outcome is apt to be unfortunate.

Vita Edwardi Secundi

Acknowledgments

I should like to extend my grateful thanks to two fine authors and historians who have assisted me in my researches: Paul Doherty, who so kindly and generously sent me a copy of his authoritative 1977 thesis on Isabella of France, as well as the advance proofs of his fascinating book Isabella and the Strange Death of Edward II; and to Ian Mortimer, whose excellent biography of Roger Mortimer, The Greatest Traitor, I also had the privilege of reading at the advance proof stage, and whose comments I have found most valuable. Thank you both, most sincerely. Your works have been inspirational and of great assistance to me in this project. I should add that, although we have studied the same sources, my conclusions are rather different, which is entirely my responsibility!

As always, I owe a debt of gratitude to my agent, Julian Alexander, for his never-ending support; to my commissioning editors, Will Sulkin and Elisabeth Dyssegaard, for making this book possible, and for their great enthusiasm; and to my editorial director, Anthony Whittome, for his sensitive editing and creative vision.

I also owe a mention to all those other persons who have helped and inspired me over the past two years, and to those who have put up with not hearing from me for weeks on end while I finished this book. They are, in alphabetical order, Jacintha Alexander; Angela and John Bender; Neil and Lesley Blyth; John and Joan Borman; Tracy Borman, Julian Humphreys, and the team at English Heritage; Terrence Cahill; Ewan and Lesley Carr at Carrbooks; Lucinda Cook and the team at L.A.W.; Jane Dunn; Sister Mary Fox; Kerry Gill-Pryde; Sarah Gristwood; Eileen Hannah; Jean and Nick Hubbard; Fraser Jansen and the team at Methvens; Roger Katz and all at Hatchards; Christian Lewis, Kate Worden, and Rosie Gailer at Random House; Jill and Wyndham Lloyd-Davies; Robin Loudon; Alison Montgomerie and Roger England at Hay-on-Wye and Chipping Sodbury; Hawk Norton at London History; Richard Pailthorpe at Syon House; Kim Poster; Deborah Queen; Graham and Mollie Turner; Christopher Warwick; Martha Whittome; and Ann Wroe.

Finally, to my much-loved family: to my husband, Rankin; children, John and Kate; parents, Doreen and Jim; uncle John; cousins Chris, Peter, David, and Catherine; and my in-laws, Kenneth and Elizabeth and Ronald and Alison: thank you all for your unstinting kindness and support during the difficult period when this book was in preparation.

Authors Note

I have generally adopted the anglicized or Latin form of names. Thus, in the interests of using the name by which she is now commonly called (and which was in fact used by many chroniclers in her own time), I have chosen to refer to the subject of this book as Isabella rather than use the French form of her name, Isabelle, by which she would usually have been known in her lifetime, Norman-French being the language of the English court in the early fourteenth century.

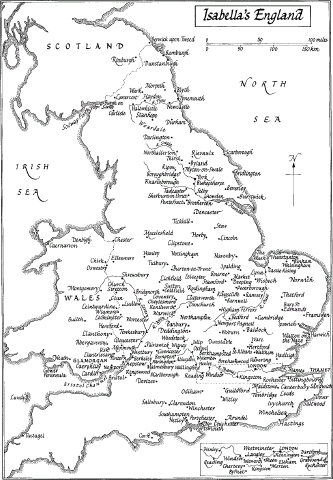

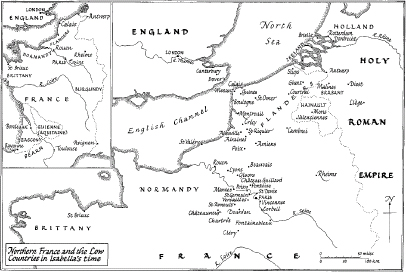

Unless otherwise indicated, place names have been given in their modern form.

Unless they are contemporary quotes that appear in the text, the chapter titles have been taken from Christopher Marlowes play Edward the Second.

INTRODUCTION

The She-Wolf of France

I n Newgate Street, in the City of London, stand the meager ruins of Christ Church, a stark reminder of the devastation caused by the Blitz during the Second World War. This is the site of Christs Hospital, the Blue Coat School founded by Edward VI in the sixteenth century, destroyed during the Great Fire of 1666, and rebuilt by Sir Christopher Wren some years later. Yet these ruins stand on the site of an even older foundation, the magnificent monastery of the Grey Friars, originally built in 1225 and later endowed and reconstructed through the generosity of pious medieval queens. In the fourteenth century, this was a royal mausoleum set to rival Westminster Abbey as the resting place of crowned heads, yet tragically its splendors are long gone, having disappeared after Henry VIII dissolved the monastery in 1538, during the Reformation.

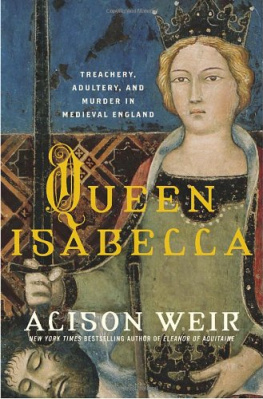

One of those who was buried in Greyfriars Church at Newgate, and whose tomb was lost, was Isabella of France, Edward IIs queen, one of the most notorious femmes fatales in history. Nowadays, popular legend has it that this sinister woman does not rest in peace but that her angry ghost can sometimes be glimpsed amid the ruins, clutching the heart of her murdered husband to her breast.

It is also claimed, even in the reputable publications of English Heritage, that this Queens maniacal laughter and agonized screams can be heard on stormy nights at Castle Rising in Norfolk, one of her favored residences. The belief still persists that, demented and insane, she was kept a prisoner here for twenty-eight years. And her unquiet ghost is also said to walk the secret passages below Nottingham Castle; she is believed to be searching in vain for her lost lover.

There is no doubt that the legends about Isabella of France paint a picture of a tragic, tormented, cruel, and essentially evil woman. And indeed, her historical reputation is not much more favorable. Since 1327, she has been more vilified than any other English queen. In her own lifetime, the chronicler Geoffrey le Baker called her that harridan or that virago, referring to her as Jezebel and to her episcopal followers as priests of Baal. Other chroniclers, although more discreet, were equally disapproving.

In 1592, in his play The Tragedy of Edward the Second, Christopher Marlowe wrote scathingly of that unnatural Queen, false Isabel and had Edward refer to her as my unconstant Queen, who spots my nuptial bed with infamy. So, too, in his controversial 1991 filmed adaptation of the play, the director Derek Jarman showed little sympathy for Isabella, portraying her as a sexually repressed virago.

Shakespeare had invented the epithet She-Wolf of France for Margaret of Anjou, the scheming, vindictive wife of Henry VI, but in the eighteenth century, when England was at war with France, the poet Thomas Gray applied it to Isabella, and it has stuck ever since. In his The Bard(1757), he speaks, with horrific significance, of the

She-Wolf of France, with unrelenting fangs,

That tearst the bowels of thy mangled mate.

In the twentieth century, the German playwright and poet Bertolt Brecht revived the same theme in his